GEORGE KUCHAR: STARVING FOR WEATHER

| August 29, 2016 | Post In 2016年8月号

“You know the way animals are…

They’re run by instincts.

You can’t expect them to behave morally.

It likes to eat, it likes to have sex…

Don’t expect too much from a thing like that.

Just take it for what it is.”

—Scarlet Droppings (1990), George Kuchar

Cinema has historically been a fecund site of moving forces. Representation and spectatorship are always laden with emotions. The myth and aura of cinema was born precisely when the train in the Lumière Brothers’ 1896 classic rushed towards the audiences and evoked visceral reactions of shrieking and fright. Breezing into the 20th century, as the non-technological potentials of motion pictures were further exploited, filmmakers advanced this medium into a kaleidoscopic field of not only visceral thrills, but also narrative, identification, and performance.

The recent turn to affect in various intellectual domains can perhaps be summarized as an attempt to differentiate affect from emotions and feelings, and an admirable effort to put an end to the oftentimes interchangeable use of these vocabularies. According to affect theorists, feelings are personal and biographical. They are labels and narratives that each of us prescribes to our emotional experiences. Emotions are social; coded performances through which we display our feelings to public. While both emotions and feelings are local, affect constitutes an autonomous level of physical experience independent of cognitive perception, a subject’s discontinuity with itself. It’s an ineffable fact about our human condition that “cannot be translated into words without doing violence.”(1)

But translation is never perfect; losses in translation are in fact productive in generating interpretative nuances. Created with a camcorder only three years after the birth of the consumer-friendly device in 1983, the late American film and video maker George Kuchar’s “Weather Diary series” (1986-1991) is essentially a rare attempt in the history of video-making to graze those affective forces that shape a person’s relationship to the body, the environment, and others, as well as the subjective experience that one feels as these affects dissolve into interiority.

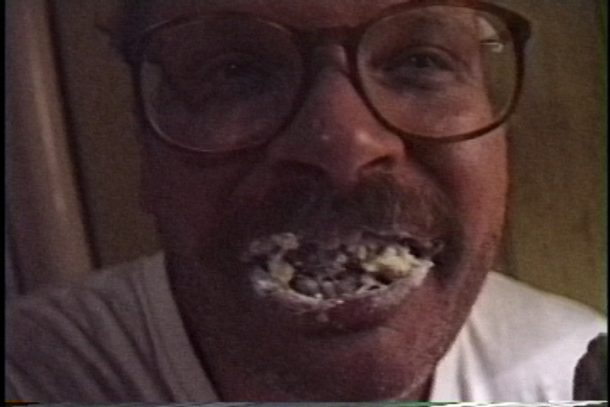

Most people’s first encounters with Kuchar’s work are distinguished with polarized reactions. They are either instantly captivated by its corrupt humour and genrebending originality, or appalled by its rampant obscenity and wretchedness. The first camp encompasses a list of American artists that includes Andy Warhol, Jack Smith, and John Waters. Meanwhile in the eyes of the latter camp, Kuchar’s work, like his on-screen persona, probably seems dreadfully self-deprecating, decidedly inappropriate, and outright weird. And they might feel so for good reasons—something that was always absent in Kuchar’s cinematic endeavours. From Kuchar’s early zero budget Super 8s made with his brother Mike in their adolescence with cheeky titles such as A Tub Named Desire (1956) and Pussy on a Hot Tin Roof (1961) to his 16mm camp classics like Hold Me While I’m Naked (1966), Kuchar’s work was indeed always laden—as hinted by their titles—with campy kicks, “corrupt” desires, and queer melancholy. These motifs grew exceptionally textured in his Weather Diary series, produced with a camcorder throughout his annual trips to Oklahoma for purposes of “storm-squatting” during the tornado season.

Prima facie, Weather Diary 3 is a formal reconstruction and restaging of the melodrama of Hollywood B film, evident in its plot centered around George’s unrequited desires (we refer to Kuchar in the diegesis as George for clarity). A 46-year old George arrives at the Reno motel in Oklahoma for another summer of “storm squatting,” but was instead welcomed by a lull in storm activity. Feeling beaten and bored, he binges on donuts and hot dogs, and voyeuristically peeps at handsome, (much) young(er) men as he strolls around the town. Suddenly the sweet and attractive 21-year-old Michael moves into the motel room next-door. Infatuated, George makes coy attempts to befriend him by taking him out to dinner and watching the weather. But eventually, Mike decides to head back home. The story ends with a brokenhearted George wandering in nature.

However, Kuchar had no intention to reenact a closed, glossy Hollywood dream through his camcorder. “The camcorder revolution was just what the doctor ordered…a laxative of cheap non-stop imagery endowed with high flatulating fidelity….My video career had begun!”(2) Capitalizing on what he referred to as a ‘despised’ medium’s portability, DIY spirit, and low-fi aesthetic, he refused seamless perfection and invented a whole new genre: a cinema of poverty in which the maker simultaneously occupies the usually separate positions of director, narrator, and subject. What Kuchar termed the camcorder’s “high fidelity” results from its demand of Kuchar’s full reliance on his immediate surroundings, including his own imperfect, even abject body as source material. The camcorder compels the maker to search for spectacles and intensity in the quotidian, a laborious process that simultaneously urges one to come to terms with the degrading effects that the ever present media landscape has on the public consciousness.

The camcorder’s instant playback function further allowed Kuchar to check against previous experiences and assign feelings (or a structure of feeling) to them through jump cuts and voice-overs. In a scene where George takes Michael out to dine at a Chinese restaurant, he chats with Michael about his interest in weather-watching. As Michael keeps on talking about his fascination with weatherinduced disasters and violence, a closeup of Michael cuts to the fortune cookies on the table, and we hear Kuchar’s tart Bronx honk: “What does the future hold for us?” As Michael cracks the cookie and reads the note foretelling his upcoming involvement with many gatherings, parties, and communications, the shot cuts to a closeup on the fan on the roof accompanied by Kuchar’s hysterical voiceover: “The world keeps spinning, we gotta…we gotta call our mothers.” By dramatizing these seemingly mundane scenes with over-emotional narration, Kuchar subtly exposed the inauthentic nature of feelings: they are always fictions into which we infold ourselves retrospectively.

Through in-camera editing—a special feature of camcorders that involves taping long shots, rewinding the tape, and inserting new scenes—Kuchar injected seemingly random shots to disrupt his videos’ causal, emotional flow. These split seconds of dissonance shed light on the two simultaneous yet separate planes on which affect and conscious perception come into play in a subject’s apprehension of the world. George and Michael’s first dinner date is depicted throughout a series of pointof-view shots. Sitting behind the camera, George extends his hand holding a drink into the frame and cheers with Michael. The scene cuts to an extreme closeup of the greasy pizza, followed by another closeup of Michael eating using a fork. Conventionally, the cheers would have directly led to the closeup shot of Michael; that is, their interaction should arouse an infatuated George to look lovingly into Michael’s eyes. The interposition of the closeup shot on pizza, which signifies George’s physical drive to consume food, is a visual excess that cleverly hints at the “parallel processing”(3) of affect and intention. Similarly in another scene, George visits Michael in his motel room. A medium shot of Michael looking directly into the camera cuts to a piece of feces floating in a toilet, followed by an extreme closeup of George’s hand gently stroking Michael’s diary on the table. Kuchar’s exquisite uses of jump cuts serve as subtle cinematic simulations of the workings of affect on George’s body: “the subject’s discontinuity with itself, a discontinuity of the subject’s conscious experience with the non-intentionality of emotion and affect.”(4)

Kuchar’s “Weather Diary series” are filled with these slippages that invite us to conjecture the precariousness of living in the world. Hunger may well arouse horniness. Beyond cognition and reasons, affects move us; just like weather, violent and unpredictable. However, while affects are facts, Kuchar’s firm belief in their sovereign power over every other aspects of being human reflect a deliberate retreat. Gene Youngblood wonderfully summarizes these diaries as “about a man who seeks release from the world in self-obliterating confrontation with the sublime…[where] George retreats to a run-down motel in Tornado Valley where he eats Instant Possum and waits for a twister to lift him into the sky.”5 But thankfully there was the camcorder, something Kuchar turned into an extension of his body. Through video-making, Kuchar managed to cope with his own ineffable melancholy and find poetry in affects’ shimmers.

———————–

1. Anna Gibbs, “After Affect: Sympathy, Synchrony, and Mimetic Communication,” The Affect Theory Reader, edited by Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010, P. 200.

2. George and Mike Kuchar, Reflections from a Cinematic Cesspool, Berkeley: Zanja Press, 1997, P. 123.

3. Anna Gibbs, “After Affect: Sympathy, Synchrony, and Mimetic Communication,” The Affect Theory Reader, edited by Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010, P. 199.

4. Patricia T. Clough, “The Affective Turn: Political Economy, Biomedia, and Bodies,” The Affect Theory Reader, edited by Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010. P. 206.

5. Gene Youngblood, “Underground Man,” Video Data Bank, web.