Fu Jingyan: Arrow Paradox

| July 18, 2018

View of “Arrow Paradox – Fu Jingyan,” 2018, Platform China Contemporary Art Institute, Beijing. Courtesy of Platform China Contemporary Art Institute.

View of “Arrow Paradox – Fu Jingyan,” 2018, Platform China Contemporary Art Institute, Beijing. Courtesy of Platform China Contemporary Art Institute.

Peering into Shenyang-based artist Fu Jingyan’s world is to peer into an enigma, but one which is not altogether impregnable. To a certain extent, the constitution of this strange world is intelligible. Various elements surface again and again, altered or in different combinations to mystifying and sometimes humorous effect. There are mysterious mechanics at play here, and its unclear whether this repetition and reshuffling constitutes order or chaos. Regardless, it’s apparent that Fu’s work breathes air onto itself.

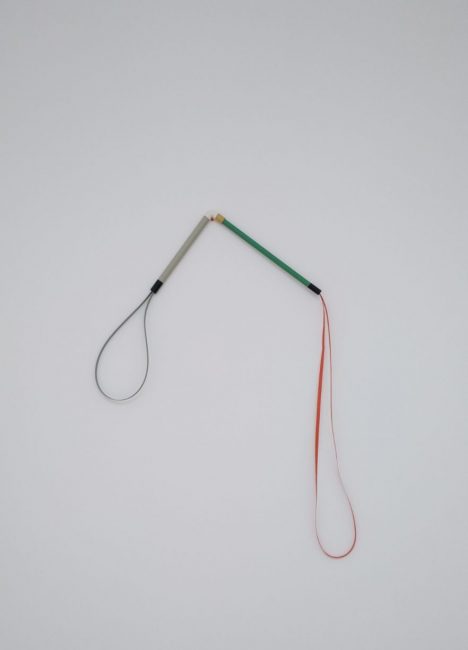

Fu Jingyan, Dialogue 1, 2018, sculpture, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Platform China Contemporary Art Institute.

Fu Jingyan, Dialogue 1, 2018, sculpture, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Platform China Contemporary Art Institute.

Arrow Paradox, curated by Dai Zhuoqun, is the artist’s third solo exhibition at Platform China. The show opens with a sculpture entitled dialogue 1 (2018), which consists of a thin corner section of colored pipe mounted to the wall, with looped plastic strips hanging noose-like from either end. The piece leaves the dialogue open-ended and very much hanging (no pun intended), offering a nice foray as to what’s to come.

Featuring recent paintings and sculptures from the last three years, the exhibition is framed by four wall texts selected and written by Dai which provide something to chew on while walking through the show. As their titles (“I. Real Illusion”, “II. Arrow Paradox”, “III. Achilles and the Tortoise”, and “IV. Unconscious Logic”) suggest, these texts find their underpinnings in philosophy, posing such questions as “How true is the truth? How real is reality?” Those versed in philosophy will also recognize in them allusions to the Greek philosopher Zeno’s paradoxes, and the specific paradox from which the exhibition gets its name refers to the argument that a flying arrow is actually not moving at all — because in every instant, the arrow is simply where it is (i.e. at rest), and time is composed of instants. As Dai’s text asserts, “Time is drawn away, leaving pure existence. A flying arrow is motionless because the current instant constitutes eternity.”

View of “Arrow Paradox – Fu Jingyan,” 2018, Platform China Contemporary Art Institute, Beijing. Courtesy of Platform China Contemporary Art Institute.

View of “Arrow Paradox – Fu Jingyan,” 2018, Platform China Contemporary Art Institute, Beijing. Courtesy of Platform China Contemporary Art Institute.

These writings challenge our conceptions of time, movement, and change, and what’s particularly interesting in these provocations is how they are made to encompass the concerns of art, such as an artist’s intentionality or an object’s meaning. Fu’s works already tend to have a philosophical air to them in their simultaneous stoicism and absurdity, and these texts provide them with compelling, though in true philosophical style, at times convoluted discourse. At their most basic level, the texts reflect in print what is visually depicted in Fu’s works (I’m thinking here of tortoises as in “Achilles and the Tortoise”). At their most expansive, they do what Fu’s work does best: provide little resolution, but a lot of space to fill.

The figures and elements that populate Fu’s paintings are easily recognizable ones, but Fu renders them in a simplistic and at times unfinished manner — most are only silhouettes — which makes them nebulous and creates a dearth of information that can be gleaned. At the same time, such rendering keeps the door open as to what they could be. Fu’s compositions afford many associations, all of which seem equally viable, and the impulse to maintain receptivity in his works is also part of the reason why he tends to keep his titles neutral or vague, opting for names such as “Figure” or “Figure and still life”.

From left: Fu Jingyan, Figure 6, 2018, oil paint, 180 x 160 cm; Figure 7, 2018, oil paint, 160 x 145 cm; Figure 1, 2018, oil paint, 120 x 80 cm. Courtesy of Platform China Contemporary Art Institute.

From left: Fu Jingyan, Figure 6, 2018, oil paint, 180 x 160 cm; Figure 7, 2018, oil paint, 160 x 145 cm; Figure 1, 2018, oil paint, 120 x 80 cm. Courtesy of Platform China Contemporary Art Institute.

In the triptych of paintings that opens the main exhibition space, Figure 7 (2018), Figure 1 (2018), and Figure 6 (2018), all featuring the silhouette of a woman with a low bun on either side of her ears, I at first imagined in their blank visages the bulging eyes and raving grins of George Condo’s loony characters. Looking at them again however, I wondered if gentler faces would better suit them.

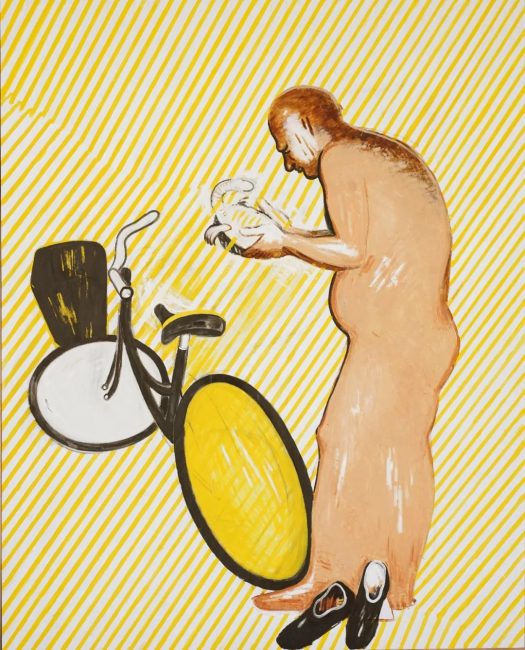

Fu Jingyan, Street 3, 2017, oil paint, 200 x 160 cm. Courtesy of Platform China Contemporary Art Institute.

Fu Jingyan, Street 3, 2017, oil paint, 200 x 160 cm. Courtesy of Platform China Contemporary Art Institute.

In addition to women’s silhouettes, pineapples, tortoises, stripes, and sun rays are among some of the more recognizable repeated elements in these works. In street 3 (2017), a full-bellied man contemplating a tortoise with a phallic head stands beside a starkly rendered bicycle against a striped background (there is the feeling at times that Fu’s paintings exist outside the confines of time and in a world of limbo, where movements are nonsensical if not inconsequential). The tortoise reappears with its legs tucked inside its shell in the adjacent painting, The Tortoise and the Hare (2018).

Fu Jingyan, Still Life 1, 2017, acrylic paint, 109 x 79 cm. Courtesy of Platform China Contemporary Art Institute.

Fu Jingyan, Still Life 1, 2017, acrylic paint, 109 x 79 cm. Courtesy of Platform China Contemporary Art Institute.

The common threads between the paintings are many, and while the more obvious ones initially pique your interest, it is discerning the less obvious ones that ultimately draw you back. Take Still life 1 (2018), for instance. While it appears that this piece is the black sheep in the exhibition, being the only entirely abstract work in a land dominated by figures and objects, in actuality its almond and crossbar shapes, indeterminate undulating upper form, and expressive brushwork are recurrent elements as well. These works reward close looking, and repeated elements feel like breadcrumbs laid out for us along a path — although whether this path actually leads to anything is questionable. There is an odd playfulness and humor in Fu’s paintings that suggests what we get is what we get, no need to complicate things further.

Fu Jingyan, Wait for the new shock 2, 2016, mixed media, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Platform China Contemporary Art Institute.

Fu Jingyan, Wait for the new shock 2, 2016, mixed media, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Platform China Contemporary Art Institute.

After circling the exhibition a few times, a familiarity begins to form with Fu’s visual vocabulary. However, one sculpture insinuates that no matter what conclusions may be drawn now, the pieces will scramble again and those conclusions may be rendered moot. Wait for the next shock 2 (2016) consists of painted wooden stair posts held together in a large, precarious formation. As its title suggests, the work looks as if it is merely in a transitory state, and it is only a matter of time before the next convulsion rocks it into another arrangement. And of course, the piece is also more or less visual manifestation of flying arrows rendered motionless: its stair posts appear like missiles in the midst of colliding before someone pressed the pause button.

These works are a nice reminder that movement and change simply occurs, not necessarily with any purpose in mind —and in fact maybe it is not even occurring as we think it to be at all. Similarly, it would be foolish to assert that Fu’s works specifically indicate anything beyond what is seen, or that there is anything specific they are meant to indicate. Rather, the work simply exists and sustains itself. But while they offer little in terms of resolution, these pieces nonetheless seduce. They accept anything you may have to offer — and so long as you have something to offer, they have the space for you to fill.

View of “Arrow Paradox – Fu Jingyan,” 2018, Platform China Contemporary Art Institute, Beijing. Courtesy of Platform China Contemporary Art Institute.

View of “Arrow Paradox – Fu Jingyan,” 2018, Platform China Contemporary Art Institute, Beijing. Courtesy of Platform China Contemporary Art Institute.