Glacier 3000

| March 9, 2021

You died.

I cried.

And kept on getting up. A little slower.

And a lot more deadly.

—Assata Shakur, STORY, 1987

2015

In 2015 I received an email from you, a journalist asking if I would be interested in talking to you in relation to an article about my practice that you were thinking about writing for the New York Times. That’s how I met you, Kim Wall, a freelance journalist writing “about hackers, hustlers, Vodou, vampires, Chinatowns, atomic bombs, feminism, etc” according to your Twitter bio. You went on to become a dear friend. At the time we had a pleasant talk, but the article was never published. I had no clue what happened to it, neither did I read a draft— in any case, the idea of reading, seeing or hearing myself in any mediated way always tenses me up.

We never spent too much time together IRL. Thinking about it, we have only seen each other twice. Or maybe even once? No, it was twice. The second time was when you went to Shanghai to write about the opening of the new Disneyland. But since the first phone call we have written to each other almost daily. I still text you; only now there is never any reply. Sometimes for those short seconds on bleak mornings, still half-asleep, I check our conversation on instant messengers, temporarily forgetting that you are no longer here.

At the beginning of the manga series Inuyasha, the warrior-princess Kikyo had a brief resurrection. A witch stole her ashes and cast a spell to bring her back from the dead. Kikyo’s body rose from the clay, but her soul did not return. It was only after Inuyasha called out her name that her soul drifted away from Kagome, the reincarnation of Kikyo, and returned to Kikyo’s body, and Kikyo came back to life.

Clickbait media keep resurrecting you without calling your name—from the very beginning, when they all made you a headline, you were always “the blonde journalist.” A mutual friend sent me a link to BBC news: that was how I learned that you were missing from the submarine. I put a Google alert on your name so that I could know whenever some discovery popped up. It soon turned out to be unnecessary. People shared updates on social media incessantly. One piece of news after another. My roommate told me to stop reading; by then we all knew you had passed. She warned me not to read the details as they emerged, because she did. So I never did. This year Netflix made a documentary about the case; it premiered at Sundance. But the streaming plan was stalled. Naturally, they made the film all about the man who took your life. But I will never say his name. As I’m writing, I realized, that I don’t even know his name.

“There has been so much writing on me, about me, but my story never exists,” I wrote in the script for my video installation Intro to Civil War (2019). But you have told so many good stories. It is from you that I learned how to observe. Writing is not the hardest part. What’s tricky is that one needs to be able to see, in the first place. Reading those stories you have covered—ranging from the relationship between Chinese shopping malls and factories in Uganda, to Cuban internet guerillas before the country opened up, to Chinese feminists in the States, to female fighters in Sri Lanka’s rebel Tamil Tigers—some of these topics were familiar to me and some not, but no matter how well I thought I knew the issues at hand, reading your stories made me realize what I knew was just a tiny fraction of the bigger picture.

I’m constantly asked to explain my work and the cultural background to which it relates. I’d like to think that I’m not terrible at that. But there seems to be so much explaining to do, and still so much that is lost in translation, partially if not completely. When I struggle to tell my own stories well, how could you have done such a good job telling those of others’?

2020

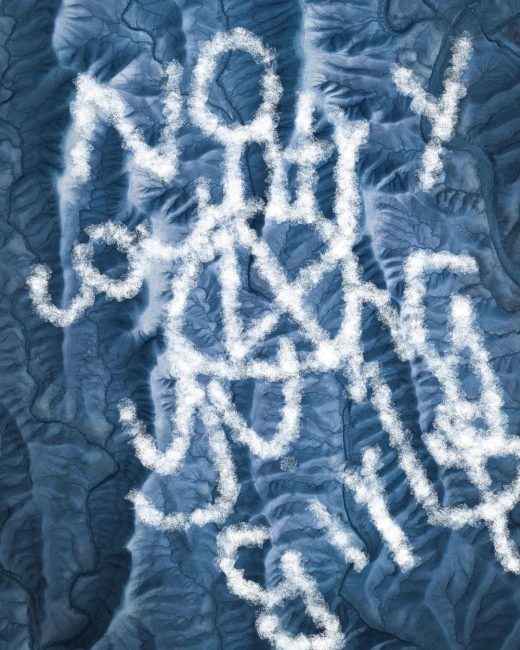

I’m currently quarantining in a hotel room next to the central train station in Geneva. An artist in my residency program had just tested positive for COVID-19. Europe is entering a second, stronger wave of infections. All my plans fell apart, again. For this project, I had planned to go to Glacier 3000, the highest peak in the Vaudois Alps, but now I can only sit on the balcony and look for found images online to Photoshop—even though I can see the snow-topped mountains through my window, right behind my computer screen. Three years after you passed, things haven’t changed much. Femmes* are still murdered IRL while being resurrected on screen. My initial plan was to research and collect social-media updates from these femmes, whose lives were taken by their loved ones, friends, relatives, strangers, or the state, and project them onto the landscapes of Glacier 3000 as a form of digital graffiti—my own lost-in-translation way of reading and retelling their stories.

Right before I had to quarantine, I walked into a cemetery by accident, and stumbled into the kids’ section. One can easily tell it’s for kids, from the size of the tombstones, and the liveliness that comes with the dolls and teddy bears, all of it forming a bleak contrast with what these objects represent. I tried to read the French epitaphs using Google Translate. One of the translations said, “When you watch it Sky at night since I will live can I go in one of the stars. So this will be for you. JMom and Dad.” These sentences don’t make sense, yet somehow, they don’t need to. I’d like to think that’s how my work functions.

In 2020 we are all stuck in different places. In a more immediate way than is usually the case. Some people are stuck in their childhood home with their mothers; I’m stuck in these perpetual waves of unrest. I came to Berlin in February for my solo exhibition, initially planning to stay for a month. As the pandemic broke out around the world, I didn’t seem to have better options than to stay. As hard as it is to see or admit, this is the year that I’m embraced again by the possibilities of life, possibilities that I haven’t really considered for a long time. It reminds me of when I first moved to New York in my early 20s. Yes, when it felt like the whole world was in front of me.

As a shamefully typical millennial who’s constantly lost in life, the answer to the one question that has left me perplexed for so long has emerged amidst all this turbulence—what am I actually looking for? As it turns out, the only thing I ever wanted is to be free, and I don’t really care what price I have to pay. Of course, we all have different interpretations of what the former means. Back when a lifestyle of roaming the world freely was ideal and possible, I learned how to live a life free from you. You once told me that wherever you traveled to, you would always make sure you write for eight hours every day. But for me, I can only do half an hour, the brief moment in the morning before the coffee kicks in, when I can keep a dream journal of things that have happened before dawn. Now I’m no longer longing for a lifestyle in which I can travel or live wherever I want. For the first time, I believe that I’m actually free.

3000

When we can’t travel anymore, images still can, faster than ever, across time and space. Now that I can only look over Geneva from my window, I find it strangely familiar. I suddenly remembered all the family albums I had from my childhood in Wuyishan. The photographs on the covers all resemble some sort of European town—mountains in the background, old bridges over little creeks. But inside the album are always one’s family photos, from the other end of the world, in a drastically different setting.

Earlier this year, a social-media campaign started on Instagram with black-and-white photos of femmes alongside the hashtag #challengeaccepted. While it is unclear whether it started in Turkey, the campaign itself highlights femicide in Turkey at a moment in which Turkey’s president commented about potentially withdrawing from a Council of Europe convention on violence against women, dubbed, ironically, the Istanbul Convention. When I saw the hashtag and photos popping up in my feed, I didn’t know what it was about until I scrolled through a post explaining the challenge to non-Turkish friends. “Turkish people wake up every day to see a black-and-white photo of a woman who has been murdered on their Instagram feeds, on their newspapers, on their TV screens,” reads the post. “The black-and-white photo challenge started as a way for women to raise their voice. To stand in solidarity with the women we have lost. To show that one day, it could be their picture that is plastered across news outlets with a black-and-white filter on top.”

There certainly have been voices expressing suspicions about the campaign, which reminds me of a common critique of female artists when they make works with their own bodies: “that’s so second-wave feminism.” As an East Asian woman, obviously, I don’t own my body. My uterus belongs to the state, the family lineage, the hypernormalized abortion ads, the kids; my breasts belong to a rapist, forever pornified imageries, the violence that won’t hesitate to cut them off in a heartbeat; and as it turns out, even as artists, we still don’t own the rights to our body. We also don’t own our screen bodies, which might be more resilient than the physical ones. But there’s a silver lining—screen bodies mutate. Femme victims can turn into murderers on screen. From Elizabeth Báthory, the fabled Blood Countess of Hungary who, during the 14th Century that killed hundreds of young girls in order, later accounts state, to bathe herself in their blood so as to retain her own youth, to Đoàn Thị Hương and Siti Aisyah, the girls who assassinated Kim Jung Nam at the Kuala Lumpur Airport without knowing–one of them wore a top that said “LOL.”

My ZOOM book club, with friends that I used to meet constantly but who can now only congregate on screen, read Andrea Long Chu’s Females during quarantine.

“Not all females are serial killers, but all serial killers are female, including the necrophiles. The entire incarcerated population is female. All rape survivors are females. All rapists are females. Females masterminded the Atlantic slave trade. All the dead are female. All the dying, too. The hospitals of the world are full of them: females in beds or gingerly walking about, full of pain, recovering, slipping away. All the guns in the world are owned by females.

“I am female. And you, dear reader, you are female, even—especially—if you are not a woman. Welcome. Sorry.”

Female, as a word, has long surpassed the biological and even structural identity—when we are only left with screen bodies, we are all penetrable. I made a video, titled T (2017-18), that tells the story of a misogynist cis man’s involuntary transformation into a female for his online customer-service job (for to be female is to be gentle, soft, and as a result, likable). It is the one work I had the most pleasure in explaining,

“You have to start talking like a girl.”

“But I’m a man!”

“From now on, you have no gender.”

Screen bodies have no gender. Screen bodies don’t belong to anybody. You can do anything to a screen body—it’s not a crime. Screen bodies exist only to be penetrated—yeah, that makes everyone female, and that’s why they are, and rightfully should be, fucking afraid of us.

Shuang Li is an artist and writer who has been sans address since 2020.