No Ghost, Just Shells: The Three Ensembles of the “Relational Aesthetics” Artist Group

| March 3, 2022

“There really is no such thing as Art. There are only artists.” With this dictum, the art-historian Ernst Gombrich introduces his celebrated Story of Art (1950). Might we infer from it that the various creative approaches gathered under the catch-all name of “Relational Aesthetics” are evidence that those in the international art field of the nineties took the art-historian’s instructions to heart? That perhaps they took it one step further even, no longer devoting themselves simply to the production of imagery, but seeking instead to foster and document their friendships with fellow artists? And if so, what sort of relationship is a “friendship” when defined in these terms? Can friendship be a precondition for the production of art?

The artists Dominque Gonzalez-Foerster, Philippe Parreno or Pierre Joseph all at some point or another mention their long-term friendship and collaborative partnerships in interviews and articles throughout the 1990s and beyond. To a large extent, their exhibition track-record reflects an organic interwovenness and fervent overlap. They were more or less the same age and had all grown up in Grenoble during the 1970s. After graduating from the city’s art academy, they rose to prominence during the 1990s and have since consistently remained active in the international contemporary art field. Moreover they’ve been hailed as the standard-bearers of what curator and critic Nicolas Bourriaud has dubbed “Relational Aesthetics” (Esthétique relationnelle) in a book of that title published in 1998.

The first time Parreno and Gonzalez-Foerster officially got to orchestrate something together was in 1988, as part of a group exhibition titled 19&&, held at Le Magasin (Centre National d’Art Contemporain). Parreno, together with Joseph and Bernard Joisten—each just about in their mid-twenties – had recently graduated from the École des Beaux-Arts de Grenoble. In the exhibition, the three worked together to exhibit their spatial installation named Siberia. In it, a backlit, disparate mix of videos, photographs and paintings was displayed in a shipping container. Despite the set-up’s somewhat crude appearance, it invariably reminded spectators of a stock-exchange, albeit for images. Included in the list of participators was a classmate of theirs, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster.

This exhibition was the first product of the city’s newly opened art center (Le Magasin) and curatorial school (L’École du Magasin, founded in 1987 is was the first international curatorial studies center in Europe). In line with the cultural revitalization policies of then-President François Mitterrand, the institution occupied a newly renovated, giant 3000 m² glass and steel-frame structure in which the Eiffel tower had been assembled eighty years earlier. The location was only a few blocks from the École des Beaux-Arts. The school operated its guiding principles from the outset: to let students master the operational modalities of a contemporary art center through concrete curatorial research and praxis, and to encourage them establish connections with emerging artist collectives, ultimately enabling them to work hand in glove and curate a commissioned exhibition by the end of the school year[1].

For this group of up-and-coming artists, the works and the display were indivisible. They shared an interest in refusing to become object-producers, instead attempting to trigger spectators’ attention within public space. In the year that followed, Gonzalez-Foerster joined the ranks of the Siberia trio, and together, in 1989, they staged another exhibition at Le Magasin titled Ozone.

Group exhibition Siberia, featuring works by Pierre Joseph, Philippe Parreno and Bernard Joisten.

As the exhibition title suggests, the convivial orchestration between these artists spread through the air like a gas. Photocopies, postcards and magazines collected by Gonzalez-Foerster related to environmental issues, Joisten’s surrealist dinosaur painting, Parreno’s surfboard and diving costume which were alternately displayed in the show and Pierre Joseph’s monumental-sized digital-composite photographic images all served to form a single ecosystem. In addition, the artists designed “derivatives” of the exhibition: a so-called Sac Ozone which contained cheap, industrially manufactured goods (lip balm, aerosol sprays, plastic dolls, an inflatable globe, etc) related to the theme, and a copy of the magazine Pour la science dedicated to the topic of “ozone,” as well as a promotional exhibition trailer: their Vidéo Ozone, which combined several video formats, was projected onto an inflatable television set in the garden of the Centre national des arts plastiques (CNAP)—whose premises were situated in the Hôtel Rothschild in Paris at the time—acquainting passersby with the contemporary links between humans, outdoor sports and nature. In fact, back then barely anyone without an interest in science was concerned with the depletion of the ozone layer and the potential crises that would result. The works on show were later acquired by the FRAC Corse but were lost in a fire in 2001. The dialogical approach on display at Ozone continued, however, in numerous collaborations with other artists such as Rirkrit Tiravanija, Pierre Huyghe, and Philippe Perrin, going on to provide an underlying constant of the French art scene for the duration of the 1990s.

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Pierre Joseph, Philippe Parreno and Bernard Joisten, group exhibition Ozone, held at Le Magasin (Centre National d’Art Contemporain), 1989. Collection of FRAC Corse.

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Pierre Joseph, Philippe Parreno and Bernard Joisten, Vidéo Ozone, 1989. Collection of FRAC Corse.

In his study of the group of artists (including the IRWIN collective) hailing from Moscow and Ljubljana (as well as one American) that took part in Transnacionala, a 1996 project that took the form of 4,000-mile road trip across America, traveling and living in a pair of RVs, Viktor Misiano points out that friendship is the sole social relationship that isn’t determined by locality, family ties, professional liaisons, ideological solidarity or sexual attraction. Friendship always constitutes discovery: a discovery of the self while discovering the other[2].

And yet, with the unfolding of a new relationship, the start of a friendship or the bonding between members of a community, comes the inevitable disintegration of old ties. For surely any new bond forged during an era in decline can be seen as an investment, a way of speculating on a potential set of new values? Numerous “friend circles” existed at the epicenter of much of the twentieth-century European avant-garde: a handful of artists with a good rapport who managed to remain independent from old-school academism and the mainstream, attempting instead to establish autonomy of thought, and who at times were met with political interference. When these people banded together, it was as if they coalesced into a fountainhead: for sure they might encounter various other tributaries, but ultimately they ended up flowing together into a single, steady stream. To paraphrase André Breton, what matters isn’t the viewpoint itself, but rather the speculative trust which causes everyone to put their eggs in the same basket.

The example of Parreno and Gonzalez-Foerster can be our entry point for discussing the exact stakes placed in this bet by the artists grouped under the “Relational Aesthetics” rubric. And perhaps it is further relevant to understand how the city of Grenoble, in southeast France, impacted their long-term friendship and media strategies.

In an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist, Gonzalez-Foerster calls Grenoble a laboratory-like city. Parreno, in turn, has elaborated on the atmosphere of growth generated by the city’s cultural and art spaces[3]. Since their childhood in this participatory Utopia, they’d witnessed Grenoble, a radical leftist bulwark, attempt to instigate social change through the planning of new housing estates and the embrace of new media. Grenoble’s neighborhood of La Villeneuve (new city), built in the early 1970s in the slipstream of the May ’68 movement, served as a lab for municipal socialism and a model for postwar communal living and community culture.

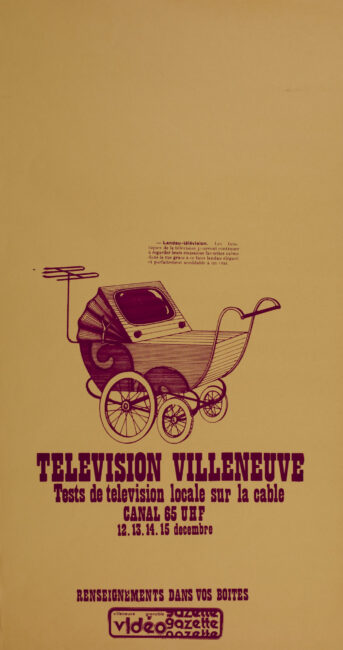

The planned neighborhood of La Villeneuve was inspired by Le Corbusier’s ideas about the modern metropolis, which entailed the design of heterogeneous condominiums, ample, convenient public facilities, well-arranged public transport lanes, sidewalks and bike lanes, etc. Meandering walkways lacing throughout the neighborhood formed connections between residential buildings, green spaces, libraries, theaters, audiovisual media-centers, sports fields, community schools and other public spaces. These corridors also adjoined other ancillary spaces in the urban periphery such as large-scale shopping malls and office spaces. In an age where cable TV wasn’t yet as ubiquitous as it is today, La Villeneuve was the first neighborhood to roll out a DIY community cable TV station: the so-called Vidéogazette, produced autonomously by local residents and broadcast exclusively to the community.

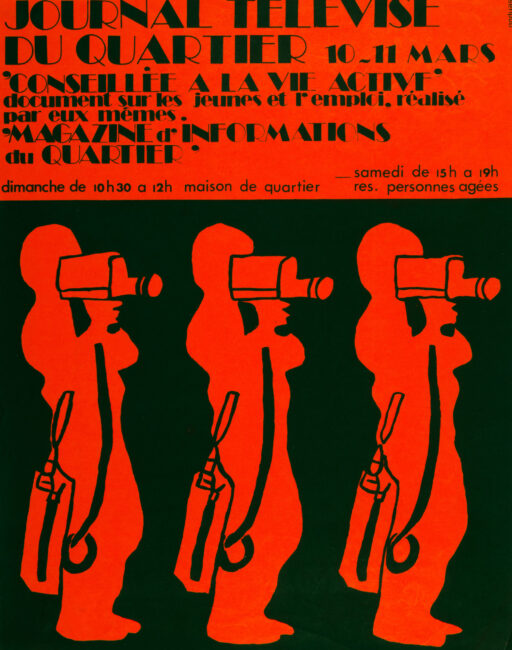

One promotional flyer for the Vidéogazette reads as follows: “Wherever there is a consumer, there’s a producer and a potential creator!”(Partout où il y a un consommateur, il y a un producteur, un créateur possible[4]) This demonstrates an early awareness about the potential of the new media to become a liberating tool, an awareness that anyone anywhere could produce as well as consume mediated images. In a sense, anyone holding a camera could become a soldier, every “wheelbarrow TV” or so-called télé brouette a weapon to be used in battle. This strategy of guerilla warfare through images had already fulfilled an agitprop function in the Californian labor movement spearheaded by César Chávez, at around the same time as Marshall McLuhan (in 1964) put forward his theory that “the medium is the message.” At its core, the underlying technology of Vidéogazette was rudimentary: it required no more than a shopping trolley, a TV set, a Sony PORTAPAK portable camera set-up for on-the-spot outdoor shooting and some basic editing skills. From 1973 to 1976, the Vidéogazette shifted the medium-message guerilla warfare experience to modern community life. La Villeneuve’s original community theatre was transformed into a full-fledged telecasting auditorium called the Agora, where residents with divergent viewpoints – ranging from militant intellectuals born out of the May ’68 movement to ordinary workers and international refugees – could participate at any time, and could pass on information via live TV broadcasts, conduct political debates or stage musical performances. In addition, this provided residents with topics they could discuss with their neighbors the next day during chance encounters at the local market.

Viewed from a present-day perspective, the Vidéogazette made community television into a communication tool of direct democracy. Aside from constructing a communal space defined by media and technology, it also helped foster a new type of social relationship. We could go so far as to say that this type of participatory, mediated “local area network” (LAN) unleashed a prototype of social media on the pre-Internet world. As such, social media can be seen as the progeny of the seventies’ DIY spirit and emergent counterculture movement. The Vidéogazette combined production with marketing and fit perfectly in the category of what theorist and net critic Geert Lovink has described as “tactical media,” whereby a producer capitalizes on the value of temporary reversals in the flow of power. In practice, those producers then make the creation of spaces, channels and platforms for these reversals central to their practice[5]. This went hand in hand with the acquisition of savoir-faire. Anyone could get the hang of these audio-visual technologies, regardless of age or educational background, but in order to do so you had to take initiative, get in touch with your neighbors, partner up with them and learn this know-how from them.

Grenoble natives like Gonzalez-Foerster, who’d grown up in La Villeneuve in the wake of the tumultuous sixties and seventies, became proficient in communicating with others and the world precisely by standing in front of a mic, holding a camera and staring at the television monitors in a studio. However, not all of the neighborhood’s inhabitants consented to Vidéogazette’s implied contract of communal life. There’d always be those who preferred to remain passive and subject themselves to entertainment programs rather than participate in an endless barrage of chat shows.

In 1973 the film director Jean-Luc Godard moved from Paris to Grenoble La Villeneuve. Having borne witness to what transpired there, he offered harsh criticism of Vidéogazette’s practices, which he felt were lacking in professionalism, while also presenting his own ideas and experimental findings (with regard to the filmmaking process) in his film Numéro deux (1975). This essay-film was filmed in a flat in a social housing complex in La Villeneuve and in the director’s editing suite. It employed dialogical images on television monitors as its medium, capturing the political-aesthetic dichotomy between the factory and the landscape, between society and the family. Conversely, both Gonzalez-Foerster and Parreno have shown a consistent concern for migration and cultural hybridity, modern architecture, urban planning and everyday life throughout their respective, long-standing oeuvres, be it in Gonzalez-Foerster’s project Brasilia Hall (1998–2000) on the newly built city of Brasília, the eleven films that make up Parc Central (2006) and Le Jardin des dragons et des coquelicots, the series of public sculptures she made for Grenoble’s Maison de la culture in 2004, or in Parreno’s film projects Continuously Habitable Zones (2011) and Credits (2000).

A mere three years after its inception, the Vidéogazette project lost its financial support from the municipal government. Add to that other factors such as internal strife, the project had to come to an end. Perhaps due to the first-hand exposure, the Grenoble-based artist community were particularly conscious of institutional critique, joint collaborations and participatory democracy. In the interview with Obrist, Gonzalez-Foerster stated that they cared more about not having to rely on an institution or system and expanding the life of their works to other media and discursive fields, to find more room for alternatives and dialogue. Participation and interaction led to nothing but phantom democracy. It was time to go beyond the aesthetic relation of man and object, beyond the social happenings created by artists and their audience, and to start showing concern for relationships that can potentially be established between artists themselves: the connections, choices, encounters and co-productions that occur in the process. The crux was as follows: there was no mandatory “opt-in” requirement, none of the members harbored any illusions about techno-democracy, nor were people required to air collective views. The task at hand, rather, was to constantly update the platforms used to connect and communicate, to come up with new tactical media in response to new environments, and to keep setting up temporary coalitions in which people then could figure out their self-expression.

In these tactical media—the “wheelbarrow TV” in the 1970s, the images displayed in a container in Siberia and the massive inflatable TV of Vidéo Ozone during the late 1980s—the carrier was invariably a DIY, mobile television set. With the No Ghost Just A Shell project (1999–2003), initiated by Parreno and fellow French artist Pierre Huyghe, the dialogical/creative model was carried over into the new millennium and into the realm of digital media.

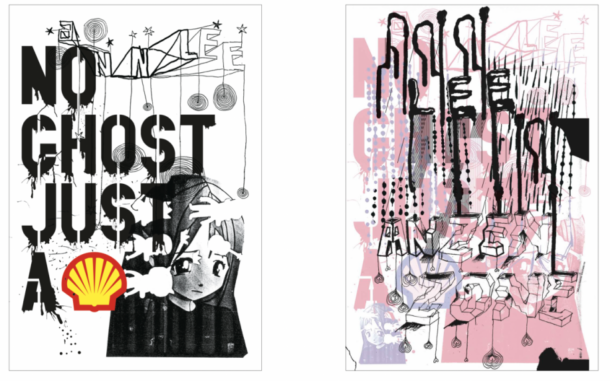

In 1999, Parreno and Huyghe purchased the rights to the raw design and 3D-model of an anime character from Japanese anime agency Kworks. They picked an intangible visual symbol that they jointly owned, and treated the exhibition as a transient platform for forming connections. The avatar, named AnnLee, was given a prolonged existence, and the identity of this hollow-eyed, ghost-like, prepubescent girl was continuously renewed as it circulated through the works of Parreno and Huyghe, as well as commissioned works by M/M (Paris), Gonzalez-Foerster, Pierre Joseph, Tino Seghal and Liam Gillick. Once again, the artists had shifted the creative battle lines from image production to the relationships and workflows established in the process of the execution, dissemination and reception of the image. In this process there was no such thing as a “minimum consensus,” only whimsical individual narratives.

Posters by M/M (Paris), designed respectively for Parreno’s and Huyghe’s project No Ghost Just A Shell and Gonzalez-Foerster’s project Ann Lee in Anzen Zone

This collaborative output based on the character AnnLee was presented in stages at the 2002 group exhibition held at the Kunsthalle Zürich. In the various media articles displayed throughout the exhibition, Parreno stated that the AnnLee project reflected an “aesthetic of alliances[6],” although admittedly the semantics of his statement were somewhat fuzzy: was this “alliance” a conflux of people who identified as a group in order to work towards a shared political goal, or just a bunch of partisan chums? Whatever the answer, said aesthetic involved the formation of a community. Compared to the historical avant-garde, the artist communities of the 1990s appeared opaque on the surface and seemed to be lacking in openly expressed viewpoints and a recognizable aesthetic. Still, they were a remainder of the avant-garde’s collective mindset, and had arisen from a resistance against and appeasement of the surging individualism of their time. The core problematic that drove the project was this: ‘How can various egos be allowed to form on a single semiotic basis in such a way that the collective stays equally recognizable for its members, while also retaining a uniqueness for everyone involved?’[7]

No Ghost Just A Shell was meant as a nod to these convivial orchestrations on their behalf. Parreno once said in an interview that since their time spent at the academy, the Grenoble crew had already been on the same wavelength, namely about the exhibition being more than just an add-on to the artworks, but rather the only, true (artistic) object[8]. It creates links between artworks and between individuals. These links and dialogues are artworks in themselves. This was precisely the wager on which the “Relational Aesthetics” generation had gone “all-in” on from the moment of their emergence. If we think of AnnLee as a mere vessel, it’s because she had no self-awareness. Hence, she had no way of becoming a ghost, and could only be a conduit for dialogues, the shell of the artwork. If we regard the exhibition as a spiritual medium, it’s because it needed to become a seance (séance de medium) before it could link together all the participants involved. This then allows the desires of the super-ego to become shared, and engenders a collective trance or ecstasy. Both the spiritual medium and the vessel are gatekeepers of information and meaning. Much in the same way as the spiritual medium transmits information reflected onto him or her by other subjects, the vessel is a necessary prerequisite for long-distance communication between two subjects. While it isn’t certain whether the friendship between these artists helped spawn their projects, or the projects themselves contributed to their friendship, it’s clear that some sort of correlation and pattern rippled through their orchestrations: perhaps a yearned-for, not-yet-attained object, or some pursued, forgotten object, which greatly exceeded the scope and expectations of the individual.

Chen Min is a curator. After living and studying in France for 10 years, she returned to China and now lives in Hangzhou. She is currently pursuing a doctoral degree at the China Academy of Art.

Translated from the Chinese by Sid Gulinck

Notes:

1. In 2016, funding and management issues led to the closure of École du Magasin. For further reference, see Michela Alessandrini, Lore Gablier, Estelle Nabeyrat, École du Magasin (1987–2016): How Fitting an End, 2018.

https://www.artandeducation.net/schoolwatch/214463/cole-du-magasin-1987-2016-how-fitting-an-end

2. Viktor Misiano, The Institutionalization of Friendship, 1998.

https://www.irwin-nsk.org/texts/institualisation/

3. Nineteen faces of Contemporary Art, (Switzerland) Hans Ulrich Obrist, Wang Nai (transl.), Guangxi Normal University Press, 2020, pp. 59-62, pp. 98-101, pp. 498-501.

4. The Whole World Is Watching,VIDEOGAZETTE (1973-1976), 2012.

http://www.ecoledumagasin.com/session21/

5. David Garcia, Geert Lovink, The ABC of Tactical Media, 2008.

http://www.tacticalmediafiles.net/articles/3160

6. Press release for No Ghost Just A Shell exhibition at Kunsthalle Zürich.

http://www.mmparis.com/noghost.html

7. Artspace Editors, Hans Ulrich Obrist on the Historic Import of Ann Lee, Pierre Huyghe and Philippe Parreno’s Self-Aware Manga Creation.

https://www.artspace.com/magazine/art_101/book_report/no-ghost-just-a-shell-phaidon-5307

8. OLIVIER ZAHM interview PHILIPPE PARRENO, Purple MAGAZINE, F/W 2007 issue 8.

https://purple.fr/magazine/fw-2007-issue-8/philippe-parreno/