Rooms

| March 3, 2022

1

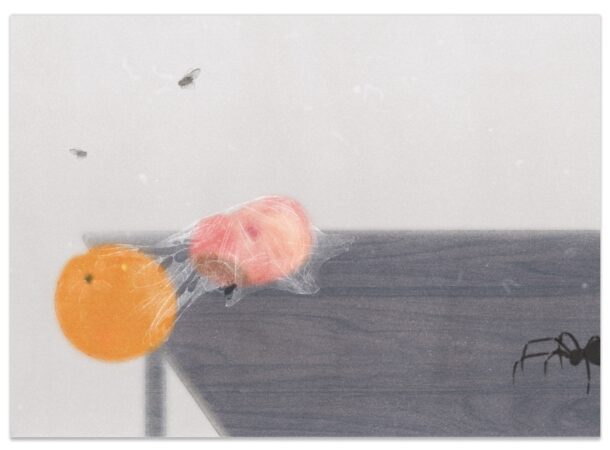

The withering peaches on the table looked morose as they secreted a sweet decaying odor. A spider crawled past, keeping its distance.

During her month in Shanghai, Locust stayed at Star’s. They slept in the same bed.

“My best friend of ten years is here!” Star shared with almost everyone around her.

Half a month passed by, and the opportunities to talk to one another were getting fewer and fewer. Every morning when Locust went out, Star hadn’t yet woken up, and by the time Locust fell asleep at night, Star wasn’t home. “but we are communicating with each other. We’re connected by crafting out a shared space.” So Locust thought to herself as she got up to clean the table.

Tomorrow there’ll be more trash on the table again, and she’ll clean it up again. From the first day Locust stayed here, she clocked Star’s reliance on take-out and delivery parcels and how she had no time to clean up after herself. “One person piles up trash, and the other throws it away. See, we’ve established a standard principle for the conservation of living space.”

“I’m not who I was. Nothing scares me anymore”, Locust replayed these words of Star’s in her mind. She no longer talked about where’s good to eat or fun to relax — things Locust is interested in. Instead, she talked about money, dreams, business connections, resources – things Locust never understood nor wanted to.

Locust felt angry. She was always mindful of defending the “past,” especially regarding Star and their shared past. However, now the authenticity of their entire relationship seemed to be fading away. Have she and Star really been friends for ten years? Why did Star speak to her like that? If this isn’t the Star she knew, then whose house is she staying at?

In Star’s house, the concept of “the past” feels even more distant. All the furniture is gleaming with an air of newness. Anything broken or old gets thrown out. The world outside her window is unfamiliar, with not even a single bird in sight. The only scenery is the unyielding sky. Just how can Star stand living here?

Locust examined the room she had just tidied up. Objects arranged orderly in sequences familiar to her. Instead of peaches, the fruit basket held her preferred oranges. Her freshly washed clothes hung out to dry on the balcony as if she were the one living there.

Star put up no challenge to these new changes. She even went as far as to say Locust’s arrival inspired her to take life more seriously. Instinctively, hearing this infuriated Locust. Yet, she felt she had no reason to criticize Star for her indifference. After all, not once had Star asked her what she spent her days doing or how she was doing.

Locust felt chained to the friendship they’d built in the past. If they weren’t already friends, they probably wouldn’t have any chance to confront each other.

The night before she left, Locust awoke suddenly. In the darkness, Star’s hand migrated up Locust’s leg, finally coming to a halt on her waist. “Oh, hug me, hug me,” murmured Star.

Locust held her breath and pretended she was dead.

2

“I envy that you get to live here,” Summer leisurely said while exhaling a puff of smoke. She extinguished the cigarette butt in the coffee pot that Snow had just handed her. More than once, Summer has claimed Snow’s technique for putting out cigarettes to be “the embodiment of wisdom.”

Summer always visits at unexpected times. Every time she knocks on the door, Snow’s caught off guard. The knock often comes when Snow’s not ready to get up, forcing her to jump out of bed and haphazardly put on clothes. Other times she’s showering and still has wet hair when Summer walks in the door. Summer comes in breathing heavily, saying she’s just passing by to check-in, then pulls up a chair and sits at the dinner table.

“Here in the Hutongs, you can drop by any time.” Snow now regretted declaring this to Summer.

Although Summer, a doctoral student in her second year, chose to stay on campus to live the life of an academic, she remains “curious about the outside world and how other people live their lives.” Her conversations usually start with talking about the complex interpersonal relationships on campus, and then she’ll move on to extolling the humanity that thrives in the hutongs. Finally, she’ll end her visit with discussions on Foucault, Isaiah Berlin, and Postmodernism.

During the intervals of Summer’s ramblings, Snow would do some planning for her day job, water the plants, stroll by the window smoking cigarettes, or even cook lunch. Snow didn’t want to appear as though she had nothing to do, or she would have to grapple with the meanings of the myriad philosophical terms Summer referenced. This way, she didn’t have to worry about saying something wrong

“Well, I’d better go.” Each time Summer had no sooner gotten everything off her chest than she hurriedly pushed out the door and left.

Snow felt that Summer came round too often but could never bring herself to mention it. After all, she was Summer’s only friend outside of the university. “If it wasn’t for you, I don’t know where I’d go,” Summer once shared.

Other than telling Snow about her recent news, Summer never invited her to do anything else. Not even to go to a nearby café. This confused Snow. Is she really a friend of Summer’s? Or just a research subject? Or even just a life-style reference?

Perhaps, Snow thought, Summer had taken a fancy to her home. So when Snow was about to leave Beijing, she asked Summer to sublet her house. Summer thought about it for a day before deciding. “Truly, it’s time for me to go deeper into life.” Then, taking one puff of her cigarette before tossing it in the newly purchased ashtray, Summer paused for a moment and said, “you can leave whatever you don’t take. This house is still your home in Beijing.”

Snow took only her personal belongings in an attempt to leave the house as it was. C lean pans cupboards full of dry goods, spices, and noodles were still in the kitchen. A row of travel magazines left on the bookshelf, and piled at the front door was dried food for the street cats.

Snow didn’t hear from Summer for a long time. And then, one day, she reached out to say she was going back to live on campus.

“Why?” Snow asked, surprised.

“I’ve experienced everything I needed to. Anyway, living on campus is more convenient.”, explained Summer. She added that cleaning the whole house was too big a workload, especially throwing out all the kitchen “clutter,” selling the magazines, and cleaning around the front door. It all seemed like a waste of time to her. “Keeping a home is hard. Modern life is hard.”

“At the very least, this proves that we live in a post-modern world.” So Snow thought as she forgave Summer.

3

“We’re best friends. So what’s the point of putting up restrictions like this?” A bewildered Iron thought to himself.

He walked into the room that Wood had just moved out of. It was a mess. With the urgency of someone fleeing, Wood just up and left as though he had disappeared into the night. The situation arose because of Li’s lack of “boundaries and restraint.” For the first time in his life, Iron began to mull over the meanings of these two concepts.

The previous day, a group of Li’s good friends came over for dinner. With no room to fit everyone, they all crowded into Lin’s room. His room was simply more spacious than the living room — this was all that went through Li’s head. He knew he screwed up. It just didn’t cross his mind to ask Woodbeforehand. Still, it doesn’t justify Wood’s acrimonious departure.

Do friends argue about things like this? So Ironthought as he stared at the big glass bottle in the corner that Woodused to brew beer. It was so heavy that Woodhad to leave it behind. Iron thought about kicking it to pieces but physically couldn’t bring himself to take a step forward.

Retreating to his room, Iron shrunk into his bed. He felt breathless, like an empty void was smothering his entire being. He thought back to the old days when he and Wood got by with only borrowed quilts and tableware. They used to improvise a makeshift bed on the floor.

Back then, they were much closer.

“Anyway, didn’t we agree we’d build this space together? We even said that we wanted to establish an inclusive open-house homeless shelter.” Iron recalled as he felt a wave of melancholy. “We have nothing more to say. Talking to you is a drain.” Wood told Iron before leaving.

The next day, Iron woke to find a leather sofa lying outside the door of the house. He recognized it. The couch had been lying abandoned in the park for a while. Wood had said he’d take it home someday.

To build a home for the homeless and take in the youth who have nowhere else to go —was both Wood and Iron’s long-time shared vision. Even if they hadn’t seen each other for several years, they still cared about this joint goal. Back when they first rented their house, they agreed to use old and discarded objects to create a grungy yet relaxing living room. They felt this atmosphere would help reduce the distance and break down barriers between people.

Every morning after the sofa’s mysterious arrival, something new would appear at the door. A small tea table with a broken leg, a creaky rocking chair, chipped drinking glasses. Iron took them all into the living room, scrubbed them clean, and found suitable places for them. He never asked if Wood was the one delivering these items. Wood also said nothing about it. They had met once on the street but only gave a reciprocal head nod. It was a show of their tacit understanding.

Two months later, Iron decided to officially open the homeless shelter. On that same day, he found there was nothing new outside of the door. He didn’t invite anyone to celebrate the opening. Nor did he tell anyone about the existence of their space. He didn’t want anyone in the house without Wood knowing about it first.

As he gazed around the living room, he felt something was missing. He walked over to the room Wood had moved out of, knocked on the door, made it as if to speak, but no words came out.

boho is a writer and translator based in London. She was born in Yunnan in 1993 and wants to keep writing stories.

Xiran Luo is a graduate student at Maryland Institute College of Art in Illustration. She was born in Changsha, 1997.

Illustration by Xiran Luo

Translated from the Chinese by Gavin Marcus