To the Countryside

| March 9, 2022

The long-term collaborative project “The Fault Zone” came into being amidst the movements, events, and disasters that unraveled in 2020. In the face of a reality full of contradictions and catastrophes, the project attempts to consider the necessity of repeated self-identification: “my” emotions, my position, my demand for truth, my thoughts about the knowledge behind the truth, and the structure of feelings underpinning my thoughts. By inviting people not limited to the arts to participate, and thus become co-initiators and formulators of the project, “The Fault Zone” aims to bring forward the senses and physicality of participation in certain events, from movement to revolution, through low-cost and flexible methods, such as Vlog, online discussion, writing, or online exhibition.

Volume I of “The Fault Zone,” titled “(Y)our movement,” comes from a prolonged conversation among the project’s three initiators, Hao Jingban, Zoe Meng Jiang, and Su Wei, which started in the second half of 2020. Located in Berlin, New York, and Beijing respectively, the three began to think about the Black Lives Matter movement in relation to themselves. In the process of daily communication, they gradually shifted their focus to the sense of belonging and detachment between self and movement. Helping each other, they created three videos, presenting three distinct attitudes toward activism. Subsequently, responding to the films by Hao and Su, the writer and curator Qu Chang created To the Countryside (2021), a video essay focused on the Yuen Long countryside in Hong Kong’s New Territory, to which she had recently relocated. The rural idyll is not without complexity, as property developers intervene on New Territory land rights, influencing personal interests and political leanings. In her work, Qu explores affection and the way it fuels and alters the narrative of violence, the fragile facade of rationality when situations trigger us to feel emotionally charged, and the complexity of empathy in Hong Kong’s recent state of flux.

To the Countryside

Hi,

I moved to this village from Prince Edward last August in order to be closer to school and also to have a change of environment. Yesterday I watched a movie at school. It was an arthouse film composed of independent chapters with stories of mundane everyday lives as metaphors for Hong Kong society at large. I felt uneasy while watching it. Perhaps the hollow self-infatuation came across as a little repulsive. Nevertheless, I wept over a number of its emotional moments. Some things just trigger the tears.

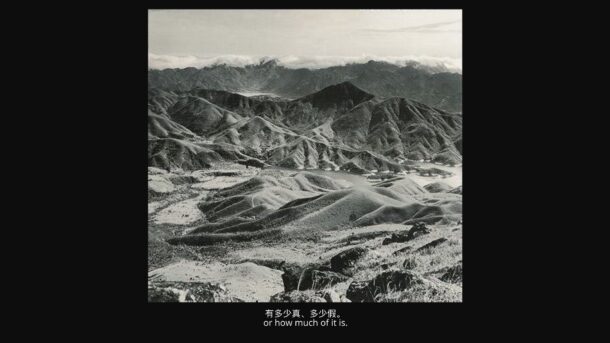

All images: Qu Chang, To the Countryside, 2021, single-channel video, 13 min 26 sec

You all spoke about qíng (feelings, sentiments, affections) in your letters. The qíng on the street that motivates the body; the qíng of collective anger and despair; the qíng peddled in songs. This is something I am especially interested in. Two years ago, when my husband and I lived in Tai Kok Tsui, we would take strolls along the seaside and sometimes sing together softly, songs like The Pearl of the East and Orphan of Asia, and shed a few tears—which was extremely self-absorbed. Those tears were sincere. But was it enough to be sincere? I truly believe qíng is able to motivate, connect, and expand. Meanwhile, I can’t help but be skeptical: we often see it overdramatized, hollowed out, attached to powerful and immovable systems, and used as a warm filter for violence. Like the song you sent from Mong Kok and its message of love and friendship shared between the female singer and the audience: is it a compelling sense of empathy or hollow self-infatuation? After all, when The Pearl of the East is played at state galas, the lyrics “my never-changing yellow skin” lurches toward a very different sentiment. Often, qíng confuses me.

I would walk through farmland like this a few times a day. Compared to what you described on the streets—the voices and noises, the vigor and volume—here it feels like another world and era. Compared to my previous apartment, near Nathan Road, in 2019, this place seems to signal a complete change of atmosphere. Sounds are dampened and silenced, friends whisper and ask each other how to break the silence after the turmoil. But maybe there’s more. Last year, a farmer friend and I talked about the polyphony in the fields. The birds, the insects, the dogs, the rustling of the plants, and many other sounds, indescribable and undecipherable. Walking these footpaths, it sometimes feels like the air and soil are frizzling with delicate voices. In the grass, there is predation, competition, codependence, symbiosis, and other relationships beyond my perception.

They sometimes give me feeble flashbacks on the factions and frictions among crowds on the streets. You know, things are never as simple as right-vs-wrong. The bacteria of power are infecting everyone. The roles of victim and culprit are usually intertwined both in the soil and on the pavements. Case in point, as a tip of the iceberg: Hong Kong’s migrant workers and refugees from Africa and South and Southeast Asia can rarely empathize with the city. Most of them will never qualify as one of “us.” Foreign domstic workers earn barely a third of the city’s minimum wage. They’re never allowed to apply for residency. The slightest visa issue can get them deported, detained, or worse. There’s this incident I’ve mentioned to you, which is still very hard for me to process. Last year in May, a week or two before the George Floyd killing, an ethnic South Asian man died from the same use of force by the Hong Kong police: suffocated with a knee on his neck, after allegedly resisting arrest. News reports were quickly submerged by other topical events. In those brief reports I found by major local outlets, not once was his exact ethnic background even mentioned. The reason I mention this is not to reduce the legitimacy of other causes. But I think societally much deeper seismic shifts are needed, in order to really talk about “care,” “change,” “hope,” and “us.” With the race issues you mentioned as an example, the reason dialogues on it have hardly taken root in Hong Kong is that, on top of the existing class, racial, and gender suppressions, the still ongoing China–US impasse has cultivated a bizarre affinity from many Hong Kong protesters toward Trumpist politics. Hence, BLM ends up on the wrong side of their viewpoint. The bacteria of power are infecting each one of us. We often struggle to see beyond the polarization or delve into the complexity.

Yet the complexity is complicated. A verdict of “complicated” doesn’t resolve the word’s ambiguity and deceit. For example, quite a few of my friends refuse to take a side because of an issue’s “complexity,” and say that taking a side means being manipulated and exploited. But is there genuine neutrality? By superficially stating an issue’s complexity without understanding or analyzing it, without generating different layers of attitudes and actions, isn’t it simply indifference? After all, whenever personal interests are on the line, the side one takes is always self-explanatory. Complexity shouldn’t be an excuse for one’s avoidance, but the very core of action. Naturally, this complexity is about the effort to examine the problems deep into their fabrics rather than what our friend’s brilliant poem calls “complicated, and vulgarly so, laced with theorized hogwash, helping reinforce the slaughterer’s cruelty on the intellect.”

A while ago, a friend told me that during the 2014 protests he spotted some suspicious individuals who would instigate physical altercations to escalate tension within a crowd otherwise showing no sign of violence. Didn’t seeing afflictions in the protesting crowd make you feel skeptical and alienated? I ask him. Of course it did, he says. But it’s impossible to maintain purity and uniformity. We still need to do what we should do. I admire that immensely. To be able to see your way forward through complexity might be just what our poet friend means by “fare forward.”

Let’s come back to this neighborhood. The complexity of the streets lives here too. The land policies in the New Territories are quite different from Hong Kong Island and Kowloon. In the 1970s, as part of a short-term solution for “developing the New Territories,” the “Small House Policy” entitled each “indigenous” male villager the “ding rights” to build and own one three-story residential building. An “indigenous inhabitant” was defined as a male “descended through the male line from a New Territories resident in the 1890s.” Recently, capital from developers has encroached further here, in the bulk-buying of the ding rights to develop properties, and in converting arable land into brownfield for profit while massively depleting and contaminating the farms. With land rights colluding with capital, “indigenous” New Territories residents’ political leanings are deeply entrenched with financial interests. When house-hunting, I was assured by the leasing agent here that this neighborhood was “pure and simple,” as the landlords wouldn’t let “funny people” like South Asians or Blacks rent a place. This is part of the reason why I was able to secure this apartment. “My never-changing yellow skin” now manages to exhibit another disturbing flavor.

There’s a farmhouse restaurant nearby, popular for its vegan western meals using only locally grown organic vegetables. It is only open on weekend evenings, and tables are usually hard to book. In summer you need to come prepared for the mosquitoes. Walking to and from this restaurant after dark, you can smell the stench from chicken coops nearby. Still, you can’t help but be captivated by the cottage charm. For a Mainlander like myself, this juxtaposition of dirt trails and the bucolic in the flesh gets pretty confusing. It makes you question whether it is real, or how much of it is. There are convoluted, bewildering little things everywhere. We are situated in different places, but perhaps can try to chart them at the same time. When you can make it over here after the Covid border shutdown, I’ll take you there for dinner.

Best,

Qu Chang

Qu Chang, a student, writer, and housewife.