Cinematic Versionists Across Asia: Four Iterations in Contemporary Art

| September 29, 2022

It’s been a hundred years since the apotheosis of live versioning practices for silent films across Asia. Such practice helped mediating the screen-based cinematic apparatus so specific to Western technological advancement. In Japan, a benshi, or film narrator, would stand next to the screen and provide live translation, dubbing, and plot explication so that local audiences could more easily understand the film. Observing its popularity, film companies further introduced silent film narration to Hong Kong and Thailand. The profession developed in Taiwan and Korea as a result of Japanese colonial invasion, and generated localized versions such as the Taiwanese bianshi and Korean pyongsa in the colonies respectively. The derivation of a version offers potential new branches and pathways. In some cases, the bianshi’s narration allowed the meaning of the film to be extended beyond the work itself. Both bianshi and pyongsa made use of the autonomous space of linguistic translation to advocate for radical political stances. Drawn by the revolutionary lure of these historical figures, contemporary artists look into the versionists’ practices to identify the structure for emancipation. Some even incorporate such practice by contributing yet another vernacular version of sorts, thus perpetuates its commitment in multiplying the autonomous speech.

Bianshi Ying-Hsiung Huang contributing to Bernd Behr’s Chronotopia at the Taiwan Pavilion during the Venice Biennale in 2013 ©Bernd Behr

Bianshi Ying-Hsiung Huang contributing to Bernd Behr’s Chronotopia at the Taiwan Pavilion during the Venice Biennale in 2013 ©Bernd Behr

Bernd Behr: Exploring the temporality of non-existence

In an era overflowing with images, you could very easily have no memories of the films you have seen, but this does not prevent the rare figure of the film narrator from leaving an impression on your memory. Film narrators were an early replacement for dubbing technologies. Becoming a film narrator today implies that memories of the audio-visual technologies of the silent film era made their mark on you. In the visual memory of listeners, how does this embodied aspect of film even commensurable with that of mobile devices and data streams?

My first memory of film narration was the opening performance at the Taiwan Pavilion for the 2013 Venice Biennale. Taipei-based bianshi Ying-Hsiung Huang, who regularly performs for the visually impaired at a public library, was invited to Venice to contribute to London-based artist Bernd Behr’s video essay Chronotopia (2013). On the night of the opening, Huang’s Taiwanese-language narration described the spatiotemporal structures of Chronotopia, while Behr’s English-language narration occurred simultaneously. Behr described the stream of consciousness of a spatiotemporal traveler giving a bianshi performance to the audience, but the tone was darker, as if he were providing the harmonizing bass notes to Huang’s narration.

The prototype for the spatiotemporal traveler in Chronotopia is Lee Guang-Hui, an Amis Taiwanese serving in the Imperial Japanese Army who survived in the jungle of the Indonesian island of Morotai for nearly 30 years, unaware that the war had ended until he was discovered in 1974. After he returned to Taiwan in 1975, his story was used in political propaganda. In one scene, Chronotopia brings us through a group of people to see Lee Guang-Hui on a screen in a movie theater. In another scene, a close-up captures a contemporary model wearing Amis bark cloth, set in a well-known Futurist ruin from the 1970s located in northern Taiwan. The scene references the plight of Lee Guang-Hui, who was forced to re-enact traditional life in an Amis Cultural Park. In 2013, the term “indigenous futurism” had not yet emerged, but in retrospect, this image that introspected the racial prejudices of settler colonialism somehow foresaw the surge in Taiwanese indigenous futurism over the last five years.

Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021), which premiered at Cannes last year, also tells the story of a Japanese holdout. However, French director Arthur Harari chose to focus on the soldier’s temporal stagnation on a remote island in the Philippines. In the jungle, natural time marches on, while he remains suspended in a perpetual state of exception. Behr’s Chronotopia places the focus on Lee Guang-Hui’s Urashima effect. In the Japanese folktale, Urashima Taro visits the Dragon Palace and stays for a few days, upon returning, hundreds of years have passed. The real takeaway from this story is that the return to society does not imply the recovery of an orderly sense of time; in fact, it creates a strong temporal dislocation. Behr re-shot the video documentation of Lee Guang-Hui getting off the chartered plane in Taiwan, showing the moment he realized that things were not what they had been. The power to write history had already shifted from the Japanese colonial government to another settler regime that is the Republic of China. Lee Guang-Hui’s indigenous name was Attun Palalin, while local sources call him Suniuo. The colonial conscription system changed his name to Teruo Nakamura. Upon his return, he was given yet another entirely unfamiliar Chinese name: Lee Guang-Hui, which stands for the glory of National Day. Swept up in the media offensive, he is bewildered by the spotlight and thus rendered into a captive subject in need of the techno-linguistic mediation of bianshi.

During his residency in Taiwan, Behr learned about the use of the autonomous space of linguistic translation for the purposes of political subversion in the Taiwanese-language bianshi tradition. Therefore, Chronotopia stakes critical junctures in the reverse narrative of Lee Guang-Hui, the prisoner of the film, on Taiwanese bianshi. In the narrative, the spatiotemporal traveler in Chronotopia switches freely between different characters: from the bianshi Lü Su-shang (1915–70) to the ghost of Lee Guang-Hui to, in the end, Ying-Hsiung Huang narrating Chronotopia for the visually impaired in a library.

Let us return to 2013 and the time of Huang’s live bianshi performance. In that performance, Huang stresses the ontological relationship between image and time just as the on-screen footage presents the dialectical relationship between present and past. His bianshi style is also reminiscent of Henri Bergson’s views on film: the dialectic between pure perception and pure memory. This narrative mode may stem from the cinematographic style of Chronotopia: the use of detailed close-ups, the extension of time through fade-in transitions, the created feeling of a spatiotemporal loop, the linking of the beginning and end of every shot, and the interpretive space reserved for the bianshi are all reminiscent of Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962), an epitome of a film genre that reserves an active place for the voiceover. In Chronotopia, a film that reserves a place for the bianshi performance, Huang further sums it up as presenting the “vibration (tin-dang) of time”

However, in Taiwanese, the word “tin-dang” more often means “movement,” so is the essence of the “time-image” really the vibration of time or the movement of time? This clinamen between Chinese characters and spoken vernacular is a philosophical translation difficulty triggered by Taiwanese bianshi, but it also brings the granularity of sound back to the chronotopia in the film.

Chen Chieh-jen, Realm of Reverberations, Performance lecture, February 16-18, 2016, Shibaura House, Tokyo. Photograph: Masahiro Hasunuma ©Chen Chieh-jen Studio

Chen Chieh-jen: Yaoyan Films

Since 2011, Taiwanese artist Chen Chieh-jen has developed a series of works around Taiwan’s leftist bianshi and the countless versions of film narrations they created. This brings to mind the cinematic versionist (dianying banben zhuyizhe), a term coined by Thai scholar and curator May Adadol Ingawanij for these film narrators. When combined with Chen Chieh-jen’s understanding of a bianshi as someone who creates countless dissenting opinions, we could also apply Ingawanij’s term of “cinematic versionist” to Chen’s idea of yaoyan films. Chen’s historical source is mostly the Taiwanese Cultural Association’s traveling film-screening crew that operated in 1926 and 1927. At the time, the bianshi who performed across Taiwan used slang, local dialects, and indigenous languages to reinterpret silent film plots that originally had no anti-colonial intent. Audiences responded with applause and whistles. In this way, Chen proposes that we should examine events that happen outside the screen. In addition to a subversive film experience that separated the sound from the image, these creative interpretations, more importantly, guided audiences in generating “countless immaterial anti-colonial films.” During a 2011 lecture at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, Chen played a clip from The Mass Funeral of Wei-shui Chiang (1931). This silent film recorded 5,000 people voluntarily attending the funeral of a local political activist. After the screening, Chen Chieh-jen further explained its historical origins, saying, “I’m acting temporarily as a silent film narrator, offering my partial vision and ‘misinterpretation’ of this film.” His argument focused on how the funeral recorded in the 1931 documentary could form countless memory-films in the minds of more than 5,000 participants, too numerous for colonial authorities to ban. In an essay for the 2012 Taipei Biennial, Chen Chieh-jen further developed the tradition of politically incisive folk ballads into what he called the strategies of “yaoyan films,” in order to consider how grassroots film production could intervene in the mechanisms of governance. This time, he wanted readers to imagine the Japanese police walking toward the screen in the middle of the showing and stopping the bianshi’s performance. Here, colonial police officers become the focus of the audience’s gaze, but they also become bit players who verify the bianshi’s anti-colonial speech.

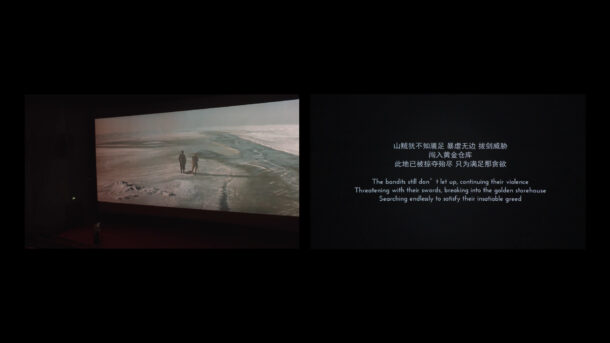

Hao Jingban, Forsaken Landscapes, HD two-channel video, 43’44”, 2018/2021 ©Hao Jingban

Hao Jingban: Beside Colonial Landscapes

Since 2018, Beijing-based video artist Hao Jingban has created a series of research-based videos on the Manchukuo Film Association, which was established in northeastern China with Japanese backing. For a time during the war, the Manchukuo Film Association was Asia’s largest film studio, and after the transfer of power, it became a basecamp for leftist film production. In one of her works on this subject, Forsaken Landscapes (2018/2021), she worked with the Japanese benshi Ichiro Kataoka, who gave a live narration of her work. Kataoka ceremonially stepped into place, to one side of a large screen that played clips of local landscapes shot on black-and-white film. As the dual-channel video is replaced with landscapes of northeastern China shot by the Manchukuo Film Association, two people are in fact narrating the film: Kataoka reads from a script comprised of Japanese poetry written about Manchuria during the 1930s, which constructs a naturalistic reflection of a colonial landscape; Hao Jingban’s voiceover attempts to recover how the filmmakers of the time viewed this landscape, whose frigid -30°C temperatures helped it to evade capture on film. These filmmakers confronted the frustration of the vast landscapes and monotonous horizon of the northeast, and the uncertainty surrounding the new aesthetic standards put in place after the studio was handed over to the left-wing government. Hao sometimes relies on the dim, reflected light of the cinema itself to portray the spirit of benshi performance; these washes of color are reminiscent of her early works on ballroom dancing in which she used the artificial light in the dance halls to disrupt the sense of time within the cinematic space. She also focuses on the contrast between the benshi’s body and the massive screen. Kataoka describes how he has noticed the disproportion between the natural landscapes and the human figures in these historical films; indeed, he metaphorically describes the expansionist immigrants in the film as “foreign objects.” It reminds us of a previous section, in which Kataoka used this idea to explain the confrontational relationship between benshi performance and the film—the benshi themself is also a “foreign object” outside of the screen.

In Mr. Miura Plays Masahiko Amakasu (2018), a work that followed Forsaken Landscapes, Hao invited a long-time actor in Sino-Japanese War dramas to both play and interview the head of the Manchukuo Film Association. In the interview, Kenichi Miura explains the pessimism of Masahiko Amakasu (1891–1945), the director of Manchukuo Film Association with a secret police background, at times alluding to the unexpected popularity of Chinese-produced Sino-Japanese War dramas in contemporary Japan. Miura compares the exaggerated, low-brow plots of these dramas, entirely devoid of individuality, to the motives behind his acting career, which are reminiscent of Kataoka’s experience giving a bianshi performance for a Sino-Japanese War film in Beijing. In a sense, Hao inviting Miura to perform could be considered a benshi narration of the anti-colonial memory within China’s mass culture. These two collaborations between Hao Jingban and Japanese performers seem to remind us that the history of the Manchukuo Film Association, which has been scrupulously avoided in official narratives, is a biased negation. Since this history of Japanese colonization in Manchuria is never officially recognized by the Chinese authority, it has effectively negated any decolonial attempt of direct criticism from the Chinese individuals. The image of Kataoka sitting beside a screen playing the colonial film is Hao Jingban’s way around this difficult subject. If not this way, how can we write a history that has been filled in by existing restrictions?

Ho Rui An’s Sun, Sweat, Solar Queens: An Expedition at the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, 2014 ©Ho Rui An

Ho Rui An: A Cinélecture

Singaporean artist Ho Rui An came to be known through his Sun, Sweat, Solar Queens: An Expedition (2014), a performance given at the opening of that year’s Kochi-Muziris Biennale in Kerala, India. The lecture begins with colonizers from temperate climates confronting heat and sweat, hence the “solar unconscious” that cast a shadow upon the colonial project. His analysis of a sweating colonial figure was even considered by one commentator to be an “unironic parody of the colonial lecture tour.” Colonial lectures were popular in 19th century Britain, involving a lecturer who would collect images of exotic lands and construct an early vision of globalization for the European middle-classes. From this, we realize that film narration is a technique for conveying information, but it also highlights the power to obtain that information.

Ho Rui An, Screen Green, 40’38”, 2015 ©Ho Rui An

Ho Rui An, Screen Green, 40’38”, 2015 ©Ho Rui An

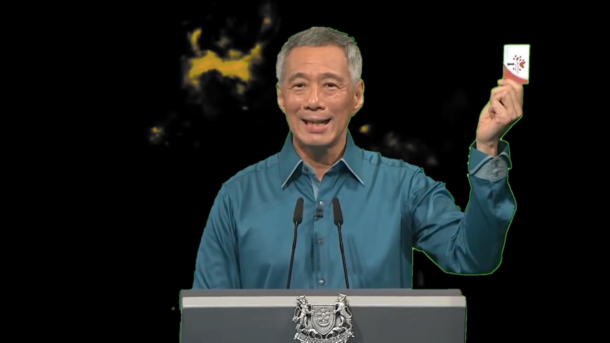

In his video installation Screen Green (2015), the placement of the television means that Ho Rui An stands in the middle of a green screen giving his narration, parodying the green screen environment from which the Singaporean Prime Minister gives the annual National Day Rally speech. In his analysis, the Singaporean political ecosystem tends to see urban greenery as a screen that conceals the technology behind it, a face that obscures the intervention of authority. Referencing Singapore’s self-bestowed title as a “garden city,” Ho sees the entire city-state as a massive green-screen studio, entirely devoid of political participation. For him, what the contemporary “cinephile” needs to do is seek out the restrictions obscured by a seemingly free and non-partisan green-screen. Around 2016, Ho used the term “cinélecture” to define his work for a period of time. He also placed his film-analysis work within the historical context of Japanese and Thai silent-film narrators and described how these narrators historically helped to circulate silent films in different regional vernaculars, citing his interest “in exploding the form of film toward a kind of paracinema.” In this way, the narrator’s vision helps to re-examine the history of the mechanisms of film: “[…] if you were to go to the cinema today, you would have the impression that the apparatus hasn’t really changed since the 1930s. Even with 3D today, it’s still pretty much a single-screen experience.”

Instead of a nostalgia for a narrator, or a kind of media archeology, Ho Rui An’s film narration focuses more on the proliferation of technologies of perception. This, in turn, reminds us that, at the time, film narrators stood next to an advanced technology, and that part of their role was in describing how this technology functioned. In Ho’s hour-long performance-lecture DASH (2016), he focuses on the ways in which globalized regimes of digital finance are transforming colonial visual legacies. From the horizon line that usually appears in Westerns to images of accidents recorded on car dashcams, a paradigm shift is taking place in these two ways of looking. He also analyzes the various images used in risk management, from black swans to risk analysts’ dissection of the movie Star Trek. Ho’s work shows us that a media movement around film narration is possible precisely because new technologies mediate the strangeness of foreign objects for the audience.

In Wu Nien-jen’s A Borrowed Life (1994), Sega leaves his son in a movie theater to go for a drink. ©LS Time

In Wu Nien-jen’s A Borrowed Life (1994), Sega leaves his son in a movie theater to go for a drink. ©LS Time

Yet the Sound of Voices Are Heard: Cinematic Versionists Stepping Forward

Now that I think about it, I first encountered a bianshi even before 2013, when I went to see A Borrowed Life (1994), a film, directed by Wu Nien-jen, set in the 1960s about the life of the director’s own coal miner father, Sega. I was young, and I did not yet speak Taiwanese. I have a vague impression that the darkness of this semi-autobiographical film was suffocating and oppressive. Before the film was over, my father took me home. Watching it again nearly 20 years later, I now know that the darkest scene is the beginning, a scene in which the miner father takes the young protagonist to a movie theater with a bianshi. In a mountain village during the 1960s, native Taiwanese bianshi still did the dubbing for Japanese films. It was only when I watched this film again that I had the opportunity to look closely for the figure of the bianshi, who avoids being captured by the director’s lens. What establishes the scene is his voice: the native Taiwanese, everyman quality is evinced by the fact that, in between giving voice to different characters, he reminds Sega to pick up a telephone call at the ticket office and sells popsicles to the audience. Sega leaves to pick up the phone and does not come back even after the film is over, leaving the boy to wait alone in the empty theater. This scene represents Wu’s first experience of film.

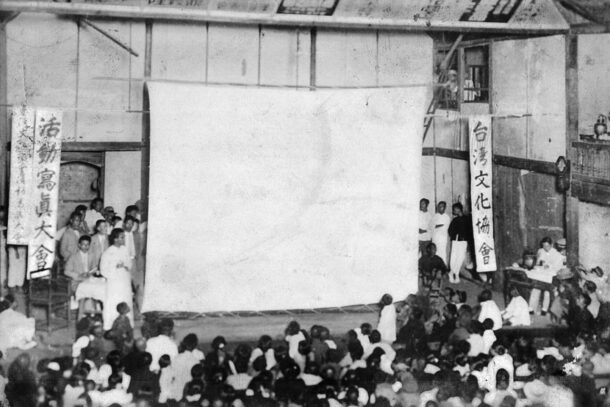

A Taiwanese Cultural Association film screening event, 1920s ©Lin Chang-feng

A Taiwanese Cultural Association film screening event, 1920s ©Lin Chang-feng

In this first experience, the bianshi is present but invisible, and the essence of the bianshi’s vocal performance in a film could be characterized as déjà entendu. The bianshi could easily go unnoticed, and the figure can only be seen through the vernacular when you go back and look. Hao Jingban tends to highlight a sensibility inherent in the social dancers from the Cultural Revolution, VHS dance tapes, and old film from the Manchukuo Film Association she has sought out. In a reverse hallucination, she uses film to articulate the spatio-temporal coordinates for several voiceless groups and their niche languages. Ichiro Kataoka understands the benshi as a foreign object outside of the film, a view closely aligned with that of film scholar Jeffrey Dym who regards the live narration as “superfluous” since it was external to the film. Compared to this Platonic foreign object, in “Outing Cinema: Four Short Films by Ho Tzu Nyen” (2013), Ho Rui An uses the concept of “ex-cinema” from East-Asia scholar Akira Mizuta Lippit to speak about how narrators (and specifically their voices) relate to the screen; films always appropriate things from outside, so the lives of all films are, to borrow Lippit’s formulation, “from, outside, or no longer.” In contrast, André Bazin once wrote that the images on a movie screen stretch infinitely outward, and the frame is actually the foreign object that restricts the outward extension of the screen.

In Screen Green, Ho Rui Andiscusses how green screen technologies leave traces around the image, 2015 ©Ho Rui An

In Screen Green, Ho Rui Andiscusses how green screen technologies leave traces around the image, 2015 ©Ho Rui An

Ho Rui An has said that, in ex-cinema “the screen is the outside, or rather, the inside turned out, inscribed out – ex-scribed.” In creating films for the visually impaired, we could consider Ying-Hsiung Huang an “ex-bianshi” who has stepped outside the bianshi model. Huang, as someone born during the 1940s, started to work as a self-taught bianshi based on his childhood auditory memories of seeing a bianshi perform. While Wu Nien-jen’s primal scene of film was one of visual trauma, Huang’s first experience of film was one of auditory healing. Behr notes one other connection between sound and the silver screen. When we see the history of film through the figure of the bianshi, the influence of vernacular drama (kabuki, glove puppetry, and pansori) is always immanent, that the birth of film is not simply a rupture with the legacy of the theater. In this vein, we can use Chen Chieh-jen’s idea of yaoyan film to ex-scribe a birthdate for yaoyan-style film. The year is 1926, in the moment in which Taiwan’s bianshi started to create countless anti-colonial film memories for audiences. Many studies of bianshi in Taiwan cite a picture from Taiwanese Cultural Association bianshi Lu Ping-ting, in which the screen looks blank because a flash was used indoors. Like Ho Rui An’s focus on green screen technologies in Screen Green, interpreting the fine green line that is left around the figure capable of “test[ing] the limits of the thinkable,” in this picture, an empty screen has suspended all the projection of mundane desires, which propels us not to miss out the audience members who have been illuminated by the flash in this moment. Together with an anti-colonial bianshi or cinematic versionist next to the screen, in this decisive moment that captures the birth of yaoyan film, they seemed to have come to the foreground.

Reference

[1] For differences in the geographic distribution of colonial film narrators, see Liu Yong, “Heian zhong de shengyin: Zuowei chanshuzhe de dianying jieshuoyuan” (Voice in the Darkness: Film Commentators as Narrators), Fuhao yu Chuanmei (Symbols and Media) 15, no. 2 (2017): 205-214. For more on the live dubbing of silent movies in China, see Zhang Wei, “Mopian shidai de peiyin yu peiyue” (Dubbing and Soundtracks During the Silent Movie Era), Xifeng Dongjian: Wanqing Minchu Shanghai Wenyijie (Learning from the West: Art and Culture in Shanghai in the Late Qing and Early Republican Periods) (Taipei: Yaoyouguang, 2013), 65-69. For the performance techniques used by Soviet propaganda film narrators in old Chinese leftist organizations, see Robert Leach, “Professor Te Ki-to,” Sergei Tretyakov: A Revolutionary Writer in Stalin’s Russia, London, Oosterhout: Glagoslav, 2021. For experiences of seeing film narration in Sichuan, Beijing, Hong Kong, and Thailand during World War II, see Li Hanxiang, “Guanzhong kouwei hennan zhuomo” (Audiences’ Tastes Are Difficult to Determine), Nanyang Shangbao: Shi yu Ting (Southeast Asia Business News: Seen and Heard), August 10, 1981, 30.

[2] For the ways in which Korean pyŏnsa resisted police inspections, see Areum Jeong, “How the Pyŏnsa Stole the Show: The Performance of the Korean Silent Film Narrators,” Journalism & Culture Research, 25 (2018): 25-54. Thanks to Ayoung Kim for this note.

[3] Bernd Behr, Chronotopia (Live), documentation of live narration by Ying-Hsiung Huang, in This is not a Taiwan Pavillion, Biennale di Venezia, May 31, 2013. 3’03”.

[4] Chen Chieh-jen extended the original Chinese meaning of yaoyan, namely “folk songs or sayings that circulate among the people and critique the current political situation,” into poetic songs that intervene creatively in dominant narratives. Chen Chieh-jen, “Yaoyan Films and Strategies,” Death and Life of Fiction: Taipei Biennial 2012, eds., Brian Kuan Wood and Anselm Franke (Berlin: Spector, 2014), 114.

[5] The term “versionist” (banben zhuyizhe) places the focus on viewers in remote areas to whom mobile screening crews traveled. Her recent research has further situated the practice of mobile film screenings within the context of multi-species communication. See May Adadol Ingawanij, “Stories of Animistic Cinema,” Antennae: Journal of Nature in Visual Culture, 1 (2021): 84-103.

[6] Chen Chieh-jen, “Cong ‘Jiang Weishui—Taiwan Dazhong Zangli’ jilupian, tan yingxiang yu shengyin cong fanzhuan dao zhibian de xingdong” (The Mass Funeral of Wei-shui Chiang: From Conversion to Qualitative Change in Image and Sound), Contemporary Art & Investment (June 2011): 36-45.

[7] Chen Chieh-jen, “The Documentary of The Mass Funeral of Wei-shui Chiang: Some Thoughts on the Dissent Images Movement from Confrontation Strategy to the Further Qualitative Change,” ACT, January 2019, http://act.tnnua.edu.tw/?p=5687.

[8] Chen, “Yaoyan Films and Strategies,” 114.

[9] Li Daoxin, “Mantie shishi yinghua zhong de wangdao letu lunshu” (The ‘Paradise of Benevolent Rule’ Narrative in South Manchuria Railway Films), Zhongguo Dianyingshi Yanjiu Zhuanti II (The History of Chinese Cinema II) (Beijing: Beijing daxue, 2010), 46. Tadao Satō, Paoshengzhong de Dianying—Zhongri Dianying Qianshi (Films Amidst Cannon Fire: The History of Sino-Japanese Film), trans. Yue Yuankun (Beijing: Shijie tushu, 2016), 1.

[10] Kevin Chua, “Crownless Power, or the Global Domestic,” Spielart Magazine. 2017, 85. https://www.academia.edu/es/36948781/Crownless_Power_or_the_Global_Domestic

[11] Chua, “Crownless Power,” 85.

[12] Andrew Maerkle, “Interviews: Ho Rui An,” Art-it, June 10, 2020, https://www.art-it.asia/en/top_e/admin_ed_feature_e/209486.

[13] See Lin Yi-hsiu, “Jiefang pingmu: Chonghui yingxiang bianshi tixi xia de neirong zhuanyi/yi” (Liberated Screen: A Look Back at the Translation and Interpretation of Content in the Film Narrator System), Cinzen, July 29, 2019, https://www.cinezen.hk/?p=9042.

[14] Ho Rui An, “Outing Cinema: Four Short Films by Ho Tzu Nyen,” Pythagoras (Singapore: Michael Janssen, 2013), 22.

[15] Phone interview with the artist, March 2022.

[16] Ho Rui An, Screen Green live performance at Para Site, Hong Kong, 2015. https://youtu.be/2Lg0Fu2ss5U?t=2386

Zian Chen is an editor and curator based in Shanghai. He periodically collaborates with artists and writers to develop alternative frameworks for thinking and speculation.

Translated by: Bridget Noetzel