Appropriately Crap

| November 1, 2023

The Writer’s Strike

In early May 2023, a pivotal labor movement began, marking the most substantial strike for the Writer Guide Association (WGA) in over a decade. As known as the Writer’s Strike, the crux of the dispute centers on writers’ income, compounded by the rise of streaming media and the pressing need to address the adoption of generative artificial intelligence tools, such as ChatGPT. This recently launched chatbot, a product of San Francisco-based startup OpenAI—backed by some of the biggest names in the tech world—has sparked swift and extensive societal protest against AI, rapidly infiltrating the media landscape and everyday life.

Protesters congregating on 43rd Street in Manhattan, New York, during a demonstration held on May 18th.

Courtesy zzyw

During the Writer’s Strike, one of the key demands made by the writers was to restrict the use of generative AI tools, such as ChatGPT, to research and edit tasks rather than allowing them to generate content from scratch. This demand reflects a growing concern among writers about the potential automation of their jobs. The strike is a turning point in the ongoing discourse surrounding AI technology and its impact on various industries.

The Writer’s Strike not only sheds light on the concerns of writers but also triggers a broader debate on the role of AI in various industries. The strike has fueled discussions on the advantages and drawbacks of employing AI, particularly in content generation. Moreover, it has raised important questions about the future of work in an increasingly automated world. Proponents of AI often highlight its ability to boost productivity, citing instances where it can transform a vague concept into a well-developed draft. While these capabilities are indisputably valid, an inherent assumption dismisses the time and effort to refine ideas into polished drafts as wasteful, suggesting that automation can enhance this process for everyone’s benefit. On the contrary, many scholars and researchers caution about the potential risk of diminishing the creative space of the human mind through d machines and algorithms. These concerns span a broad spectrum, touching on philosophical, ontological, and epistemological aspects of human creativity, authenticity, and socioeconomic equality.

Stepping back slightly, we can discern the underpinnings of our current situation – a long-standing trend in the tech industry: the relentless pursuit of seamless, frictionless experiences.

Don’t Make Me Think

Back in 2012, as I was gearing up for a long flight, it was the perfect chance to dive into something new. In my early 20s, unsure of what I would do for my career, nor did I know what I liked, I thought, “Why not explore user experience design?” After scouring the internet, I stumbled upon a quirky 200-page book filled with eye-catching visuals and witty lines. It was called Don’t Make Me Think, it was initially published in 2000 and later received many revisions due to its popularity. Its lighthearted title says it all. It came highly recommended for beginners like me, who wanted to get a taste of user experience design—an emerging field whose popularity had been on the rise since the 2010s, partially influenced by the dominance of iOS devices. The book gained mass popularity, sold more than 300,000 copies, and was referenced in college and online courses. Originally intended as an accessible introduction for novices, the book’s brilliantly apt title mirrored the prevailing ethos of making technology frictionless for its users. This message is deeply ingrained in Today’s User-Centered Design (UCD) and Interface Design principles. The catchphrase, “don’t make me think,” encapsulates this idea — design should minimize its user’s cognitive load to ensure a frictionless experience.

The 2nd edition of Steve Krug’s Don’t Make Me Think.

Image by Phatzui, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0, sourced via Openverse

In the field of computing, the frictionless motto has been around for quite some time. Computer scientist Mark Weiser, often regarded as the father of “pervasive computing” (also known as Ubiquitous Computing), introduced this groundbreaking concept around 1988, as detailed in his influential article “The Computer for the 21st Century,” published in Scientific American. Weiser’s vision emphasized the seamless integration of digital technology into our everyday lives, intending to make technology so unobtrusive and natural that it becomes invisible. These principles have had a profound impact on the landscape of modern software, resulting in a concerted effort to develop and advance the field of UCD to produce more profitable digital products. This drive is vertical, to maximize user engagement and time spent on a product, and horizontal, as products aim to appeal to as broad a demographic as possible, often at the cost of privacy and user agency.

As digital products gradually permeated every aspect of our lives, the influence of UCD and its derivatives has significantly influenced the way we perceive and interact with each other. In 2011, an influential author and activist, Eli Pariser, published his thought-provoking book The Filter Bubble: What The Internet Is Hiding From You. Pariser’s work served as a wake-up call, sounding the alarm on the perils of online filter bubbles, a phenomenon driven by algorithms tailored to individual preferences, interests, and behaviors. These personalized algorithms construct information bubbles that isolate us from diverse perspectives, compromising our ability to make well-informed decisions. Unfortunately, despite Pariser’s warnings, the impact of filter bubbles has only grown more pervasive, infiltrating every facet of our cultural landscape.

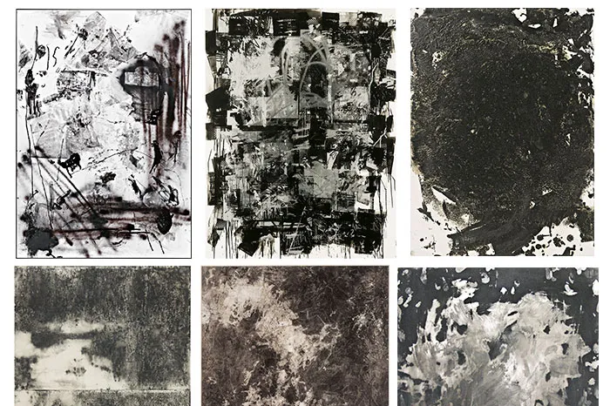

Three years later, after Pariser’s book was published, Jerry Saltz, one of the most respected art critics in the Western world, published an article on Vulture, the cultural and art outlet of New York Magazine, titled “Zombies on the Walls: Why Does So Much New Abstraction Look the Same?” In the article, Saltz coined the term Crapstraction to refer to formulaic and unoriginal abstract art that he saw as prevalent in the art world. He argued that this trend was driven by the desire to create an easily digestible and marketable aesthetic, resulting in a lack of substance and innovation. The rise of Crapstraction can be linked to the increasing influence of recommender algorithms in our digital landscape. These algorithms, responsible for curating our online experiences, prioritize content that maximizes user engagement and satisfaction. Consequently, they often promote formulaic, homogenized content that adheres to the lowest common denominator of taste. Much like most modern technology is designed for seamless user experience, recommender algorithms are the promising successor to bring automation to a higher level – generating endless content for the user’s thirst. In the name of digital smoothness, the algorithmically curated endless content stream forms millions of false cultural paradises where similar ideas are circulated and reinforced, often with little room for alternative perspectives.

Title image of Zombies on the Walls: Why Does So Much New Abstraction Look the Same? by art critic Jerry Saltz, published on Vulture in June, 2014.

Open source

Software, Interfaces and Ideology

Media, even the computational kind, has long been subject to critical scrutiny for its cultural and ideological influences. The term culture industry was introduced by Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, key figures of the Frankfurt School – a group of prominent scholars and thinkers significantly contributed to Marxist thought, who are oftentimes referred as Neo-marxists.

In Adorno and Horkheimer’s seminal work, Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947), they included a chapter titled The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception. Here, the duo argued that popular culture operates much like a factory, churning out standardized cultural goods, including films, radio programs, and magazines. These mass-produced cultural products, they claimed, serve to lull society into a state of passivity. They stated, “No independent thinking must be expected from the audience: the product prescribes every reaction: not by its natural structure (which collapses under reflection), but by signals.” This critique appears eerily prescient when viewed as a commentary on Silicon Valley’s design principles.

Since the Frankfurt School’s critique, one could make the argument that the conditions which enabled their criticism have changed significantly. The dominance of materialistic industrial production has given way to the rise of the service sector in Western societies. This shift has reconfigured the class structure, with a new class of knowledge workers emerging. The traditional industrial working class has declined, replaced by fragmented occupations and precarious employment arrangements. Income inequality has widened, affecting social mobility and the middle class. This new context calls for an updated understanding of the cultural industry in the 21st century, one that’s shaped not by television or billboards, but streaming shows, and social media platforms, and video games.

Alexander R. Galloway, a New York based media theorist, has written extensively on the cultural and political dimensions of digital media, often drawing on Marxist theory. In his key text The Interface Effect published in 2012, Galloway examines the profound impact that digital interfaces and software have on our interactions with technology and the world. Building on top of classic marxist thinkers like Louis Althusser, He challenges the common assumption that interfaces are neutral and transparent mediators that facilitate communication between users and technology. Instead, he argues that interfaces are active agents that shape and influence our perception of the world, creating what he calls “the interface effect.” He claims that the interface effect is a form of aesthetic activity that operates according to its own logic and ends, rather than reflecting or representing reality. He also warns that the quest for invisibility and frictionlessness in user experience design might have unintended consequences. By hiding the inner workings of technology, he suggests, interfaces might also conceal the social and political implications of our actions, preventing us from understanding how technology affects us and how we affect technology. He further argues that interfaces might also obscure the power dynamics that are embedded in technology, such as surveillance, control, and exploitation.

The Weather Is Annoyingly Nice

CD Projekt Red, the esteemed Polish video game developer, weathered a challenging year as its highly anticipated RPG action game, Cyberpunk 2077, suffered a colossal failure in its initial release (though subsequent revisions eventually brought the game to an acceptable level). Within a few months of its launch, a deluge of negative reviews inundated the internet, catapulting the game’s name into the realm of Reddit memes.

In the face of such adversity, a faction of disappointed fans turned to modding as an outlet to address their needs. Unsurprisingly, the modding community surrounding Cyberpunk 2077 thrived, offering a vibrant array of functional and intricate modifications. Amidst this plethora of options, one mod emerged as an symbol of our current digital climate — the Climate Change mod. The mod was described by game journalist Fraser Brown in PC Gamers: “This Cyberpunk 2077 mod makes Night City’s weather appropriately crap.”

The Climate Change mod transforms the virtual landscape of “Cyberpunk 2077,” illustrating the dystopian cityscape.

Courtesy CD Projekt Red

The genesis of this particular mod can be traced back to a conspicuous, yet minimal flaw in the game—it’s perpetually sunny weather. Players bemoaned this unwavering sunshine, voicing their discontent with remarks such as “the weather is too damn good.” Despite the outcry from the online community, CD Projekt Red hesitated to address this aspect, perhaps fearing a potential loss of players by introducing an obviously less favorable climate.

In response to this criticism, the Climate Change mod offers a singular alteration—it transforms the game’s sunny climate into a gloomy, heavily polluted haze, evoking the atmosphere expected in a dystopian cyberpunk world. Needless to say, Climate Change jumped to top of the chart, becoming one of the most beloved mods of Cyberpunk 2077.

The narrative of climate change isn’t new in the world of modding. Unlike most industries where unauthorized modification is strictly forbidden and prosecuted by the copyright holder, the gaming community has fostered a thriving modding culture that often enhances or even surpasses the original game. A prime example is “The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim” by Bethesda Game Studios. Released in 2011, its enduring popularity stems largely from an active modding community. Using the Creation Kit provided, players have shared thousands of modifications, ranging from graphical tweaks to new mechanics, characters, and quests. Noteworthy mods like “Falskaar,” “Wyrmstooth,” and “Beyond Skyrim” have added extensive new areas and narratives, extending the game’s lifespan and engaging players well beyond the original storyline. It’s worth noting that not all mods adhere to the original game’s design or gameplay mechanics – there are plenty of bizarre or even absurd mods. These include creating intentionally glitchy graphics or replacing characters with figures from the cartoon Adventure Time. The creativity of modding transcends “doing free labor for the game development company” and often evolves into unique expressions of inspiration and aesthetic development, demonstrating a promising opening for “interfaces” to be designed collectively with diverse ideological expressions.

Mods for the World We Live In

One of my favorite media artists, Sam Lavigne, has been working closely with software and algorithms. A few years back, he created a compact, simple application titled Other Orders. What makes it “simple” is its easily explainable effect: the application offers the ability to rearrange your Twitter feed. On its minimalistic interface, there are a dozen buttons you can click, each button triggers a unique way of ordering your feed items. The options available in Other Orders span a wide range, from nonsensical to absurd. Among them are choices like “Crudely Understood Marxism,” “Highest Density,” and “Number of Numbers.”

This application, residing on a webpage, requires granting access to your Twitter account through Twitter’s public API (Application Programming Interface) to function. In the case of Other Orders, the interface design carries the intention of this work. Lavgine stated the inspiration of the work on the web page, reads:

“Recommendation engines, such as the ones powering the endless feeds on Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, are designed to maximize ad revenue and keep you online for as long as possible. Consequently, they promote the most reactionary content on their platforms. However, these recommendation systems are merely sorting mechanisms. Other Orders offers an alternative set of sorting methods optimized for different outcomes.”

Lavigne’s project serves as a prime example of an alternative order, one that produces effects amidst the ever-influential forces shaping our lives. By bringing the ordering options to the forefront instead of allowing the algorithm to work behind the scenes, Other Orders deconstructs the veneer of frictionlessness that the Twitter product designers carefully conceived. The designed interface works as an invisible shell which transforms algorithms as cinematic. As American philosopher Stanley Cavell puts it, I paraphrase: in cinema, the world of the image is present to us, but we were never present to it. (ontologically speaking, not to be mixed with the colloquial “cinematic”) As spectators of this cinematic world, we are simultaneously drawn closer to it, yet remain invisible to it. This one-sided relationship deviates significantly from the original intent of interactive media. The most common form of interactive media, the informatic technology, at least around the time it gained significant support, is rooted in the concept of promoting an input-output exchange mechanism. However, they have evolved to become the biggest facilitator for easy consumption, subtly disguised as “user-friendly.” Lavgine’s work does more than reveal the misalignment, its deliberate absence of subtlety in its artistic choices forces us to confront this evolution head-on.

Opacity for the Digital

Another one of Lavigne’s works is the “Slow Hot Computer,” a website that makes the user’s computer run slow and hot by running processor-intensive calculations. The software deliberately consumes computing resources by executing countless meaningless tasks, it consumes computing resources and generates heat, slowing down the computer to a near halt. This intentional slowing down of the computer gives the artwork its apt name, “Slow Hot Computer.” While some may perceive this software as a mere “pointless novelty,” Galloway’s perspective would likely differ. In his blog post titled “Anti-Computer,” he took the Marx’s study on ergodicity and introduced the concept of the ergodic machines:

“Ergodic machines are machines that run on heat and energy. Such machines are essentially mechanical in nature. They deal with basic physical mechanics like levers and pulleys, and questions of mass, weight, and counterbalance. Ergodic machines adhere to the laws of motion and inertia, the conservation of energy, and the laws of thermodynamics governing heat, pressure, and energy.”

Ergodic machines serve as a compelling alternative to binary digital logic, addressing critiques of the digital realm, particularly its algorithmic nature and the illusion of “frictionlessness” it presents. The Slow Hot Computer dares to transform the computer, a digital machine, into an ergodic entity. To explore this path further and delve into potential countermeasures, a promising avenue to consider is Cryptography. This field employs mathematical tools to construct robust ciphers that are challenging to crack. Cryptography stands as a prime example of how we can navigate the digital realm while developing mechanisms to counteract its pervasive and seamless influence.

Installation view of “Slow Hot Computer” at Flux Factory, NY, featuring artist Sam Lavigne utilizing a thermometer to measure the computer’s temperature.

Courtesy the artist

A few years back, we started a new series of research, which we titled after the term we coined: computational haze. Zhenzhen Qi, the other half of the zzyw collective, has written about computational haze in a short essay published in 2020:

“We need to create a digital haze that allows for a dual-existence of an object’s digital presence, enabling a condition for communication that does not reduce the sender and the context.”

Inspired by the concept of computational haze, We created a series of experiments that attempt to materialize the effect of the computational haze on the digital domain. They range from online applications, games, and infrastructure software. One of the early experiments, The Hazy Corner, created an online chat room space that is filled with “haze” – randomly selected words are hidden behind layers of description, with its encryption keys discarded after encryption, effectively turning sentences into an incomprehensible hash.

At first glance, these artistic works may appear divergent, but they share an underpinning principle – embedding a level of opacity within the digital landscape, a terrain typically characterized by its transparency. This is not an act of sabotage, but rather a thought-provoking insertion that challenges the existing norms, and introduces an element of mystery and complexity. If we look past the immediate absurdity of such a transformation, we start to see the emergence of a new era. In this coming age, the age-old relentless pursuit of productivity steps back, making way for a newfound appreciation of energy and warmth, which are not just byproducts, but necessary elements in powering our endeavors.

In this context, friction finds an important place. Rather than a hindrance to be avoided, it becomes an essential component of our interaction with the digital realm. It slows us down, yes, but in doing so, it also forces us to pay more attention, to engage more deeply, and to acknowledge the inherent complexities of our digital interactions. In a world where friction is recognized and allowed, we can move forward in a more thoughtful way – not just swiftly and unthinkingly, like a cursor flicked across a screen, but with the deliberate and purposeful pace of a mindful traveler. And it is in this richer, more engaged interaction with the digital, that the promise of true progress lies.