THE FILMS OF HUANG WEIKAI: TOWARDS AN URBAN DOCUMENTARY SURREAL

| December 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 6

Huang Weikai’s most recent film Disorder (Xianshi shi guoqu de weilai, 2009) is a richly textured digital collage that strings together a series of absurd events documented by amateur digital video (DV) hobbyists in Guangzhou. With Disorder, Huang recontextualizes over a thousand hours of found footage to create jarring juxtapositions and fractured narratives, following a rule that each subsequent sequence must never be taken from the same tape. The film has ridden a wave of praise across the circuit of venues where independent documentaries are screened in China, including the Yunnan Multi Culture Visual Festival in Kunming, the China Documentary Film Festival at Songzhuang, outside of Beijing, and the Chongqing Independent Film & Video Festival. This year, Huang also brought Disorder to the Cinéma du Réel International Documentary Film Festival in France, where it received an honorable mention, and has also screened the film in Germany, Spain, Poland, Canada and the US. Hua Hsu, writing for The Atlantic, called the film “one of the most mesmerizing films I’ve seen in ages.”

Huang Weikai studied Chinese landscape painting at the Guangdong Academy of Fine Arts. Like many paintersturned-filmmakers in China’s independent film circles—see Zhao Dayong, Li Hongqi and Gu Tao—the transition to filmmaking was natural, almost inevitable, considering the increasing accessibility and affordability of DV cameras in the 1990s. The spread of this technology fueled the rise of a mobilized, independent, and egalitarian system of documentary production, one outside of the commercial and state-sponsored mechanisms of film and television. This phenomenon also worked to galvanize independent documentary filmmakers in China as a community of outsiders who took a passive—or not so passive—position of resistance in relation to the commercial film industry.

While some would hesitate to classify the wave of independent documentary in China beginning in the early 1990s as a cohesive movement, as the films of China’s documentarians like Wu Wenguang and Duan Jinchuan began to gather momentum and name recognition in film circles both domestically and abroad, it soon became clear to young filmmakers that one could make films without big budgets, crews, and official approval. These independent documentarians were not the first to relish an apparent amateur status and produce unofficial films on shoestring budgets. With DV cameras, filmmakers could penetrate previously unexplored social spaces, documenting China during stages of monumental transformation in raw, spontaneous and provocative ways.

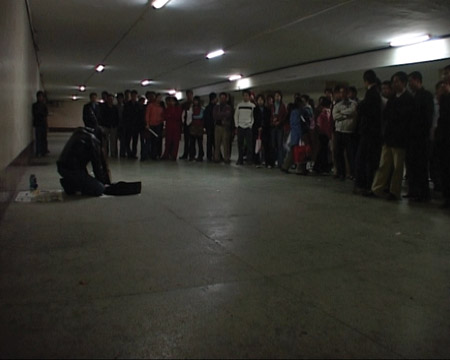

The lived realities of daily experience thus became central to DV documentary production in China. Much like the boundless possibilities opened up to the filmmakers of the French New Wave and Italian Neo-realist movements with the arrival of more portable film technologies and synchronized sound, DV cameras in China allowed filmmakers to transform the people with whom they engaged daily into the subjects of documentary films. For Huang Weikai’s first documentary project, Floating (Piao, 2005), he chose a drifter street musician, Yang Jiwei, as his subject. The film intimately documents the daily life of Yang as he performs in the subterranean spaces of Guangzhou’s pedestrian underpasses, and as he deals with the turbulent circumstances of his romantic life. Huang’s subjective gaze, and his position as both participant and observer in the social world of his subject, offer the audience a look into the lives of individuals who occupy the floating spaces of Guangzhou’s periphery.

In the opening scenes of Floating, Yang Jiwei and his fellow street performers lay on sheets of newspaper strewn about on the grass of a public park. In a familiar turn of events, the cops have confiscated their guitars. In the following scene, we see the musicians opening the guitar cases that have since been recovered from the police. Yang’s blue acoustic guitar has been smashed, its neck severed completely from the body of the instrument. An intertitle offers the timestamp “January 2003,” and Huang brings the audience into the transient space of a pedestrian underpass. A young girl, presumably a migrant from the countryside, plays violin before an opened instrument case. Huang’s camera is fixed one meter from the ground, capturing the young girl in a long shot as hordes of people drift anonymously in and out of the camera’s field of view. We then cut to a shot of Yang and his musician friend perched on a ledge near the entrance to the underpass. His friend remarks: “That girl is diligent,” alluding to the competition the performers face each day as they work to stake out their terrain in the austere tiled spaces of the underpass.

Huang frames the documentary’s narrative arc through a reverse-chronological editing structure, playing with temporality as he represents Yang Jiwei’s life as a street performer. The story begins in January 2003 and subsequently moves backward in time to December 2002, November 2002, October 2002 and further. Strands of Yang’s story surface gradually, acquiring greater clarity as the film unfolds and Huang unearths the turbulent past of Yang and his ex-girlfriend, Peach. With this backward-moving narrative direction, the pieces of Yang’s past slowly return to haunt. Huang’s deft editing style pieces together fragments of Yang’s damaging break-up with Peach, who is alluded to in the earlier chapters of the film (January 2003, December 2002), but does not emerge on screen until the narrative is rewound to the September 2002 chapter, a scene in which Huang plays both observer (documenting the unstable reality of the scene as it unfolds) and participant (being present as Yang’s friend in a tragic circumstances) during Peach’s attempted suicide. Huang is also present for intimate moments between Yang and his more recent girlfriend, including a solemn scene after she has undergone an abortion.

In Floating, the audience gradually begins to feel an uncomfortable tension, to sense an invisible body of authority gradually encroaching upon the street performers and other migrants who drift in and out of the city. The systems of control that haunt the migrant peoples are initially unveiled in abstract forms. We see performers young and old scrambling from the subterranean spaces of the city underpasses, and individuals camped out near the offices of the city authorities, where they remain in limbo after being taken in for lacking temporary residence permits and ID cards. There is no place for these people. They exist in a state of constant flux. A looming power can be felt off-screen as Huang documents the lives of these individuals who occupy transient spaces, spaces of movement where individuals of various social backgrounds pass through with anonymity. The city becomes depersonalizing, dehumanizing, ghostly, a shell containing alienated individuals who can do nothing but drift.

Floating ultimately devolves into chaos in the final scenes as Yang is carted off in an armored vehicle to an Urban Management Facility. Having been snatched up by the thuggish city inspectors for lacking a temporary residence permit, Yang is to be sent back to his hometown. After receiving a call from Yang, Huang arrives on the scene hoping to bail out his close friend. Huang, in this turn of events, becomes corporeally present in the scene as it unfolds, revealing a full shift from observer to participant as he exposes his own vulnerability and disempowerment in the face of the authorities. He scrambles on foot to catch up with the fast-departing vehicle, documenting the scene as it spirals into pandemonium. The camera flails about wildly—we hear shouts, the sounds of the vehicle’s acceleration, and Huang calling for a cab. We then hear Huang, in the back seat of the cab speaking to the driver, urging him to speed up in pursuit of the armored vehicle as it quickly fades in the distance. After a harrowing drive through the city, the cab finally catches up, Huang leaps out and sprints toward the armored car to hand Yang Jiwei a handful of cash, saying: “You can post bail on the train. Take the money and bail yourself out.” The scene fades to black under the din of car horns.

In the closing credits, we learn of a notorious incident that also took place in Guangzhou, which by way of tragic coincidence, happened in the very same month. An intertitle displays: “That same month a university graduate who had not been carrying his temporary residence permit was beaten to death at a detention center.” This chilling event points to the sometimes arbitrary deployment of authority and violence on the outsiders who occupy Guangzhou. We learn further, “three months later, China’s State Council abolished the 21-year-old detention system [for temporary residence permit violations].” The social reality in which the subjects of Huang’s documentary live thus converges with that of the world beyond the contained narrative of the film.

In Huang Weikai’s second, far more experimental documentary Disorder, he similarly explores questions about the positions of individuals in relation to urban space. In his words:

These hobbyists would just shoot with DV cameras for the sake of shooting. They’d often forget what they had filmed, or simply feel that the footage they had compiled was of no value…After watching some of the footage, I was astonished by the things they documented, so at the time I came up with the idea for Disorder. Because I had watched hours and hours of their footage, I got the idea to use a collage method to expose another side of the city. There were so many different perspectives revealed in their footage that showed the absurd side of life in this city.

As Huang’s concept for the film developed further, he decided to compose a kind of city symphony to string together the countless stories contained in the DV tapes of Guangzhou’s amateur videographers. He took inspiration from the cinematic tradition of the city symphony previously explored by Walter Ruttman in Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927) and Dziga Vertov in Man With a Movie Camera (1929). The final product, however, reveals a radical departure from the characteristics of the city symphony form. His most obvious divergence lies in the absence of a musical score. Huang’s soundtrack consists solely of the ambient, diagetic sounds of the city. Above all, Huang is most interested in excavating the surreal depths of Guangzhou, probing the absurd dimensions of living in a city that has undergone radical ruptures with the past and experienced dramatic social transformations at breakneck speed.

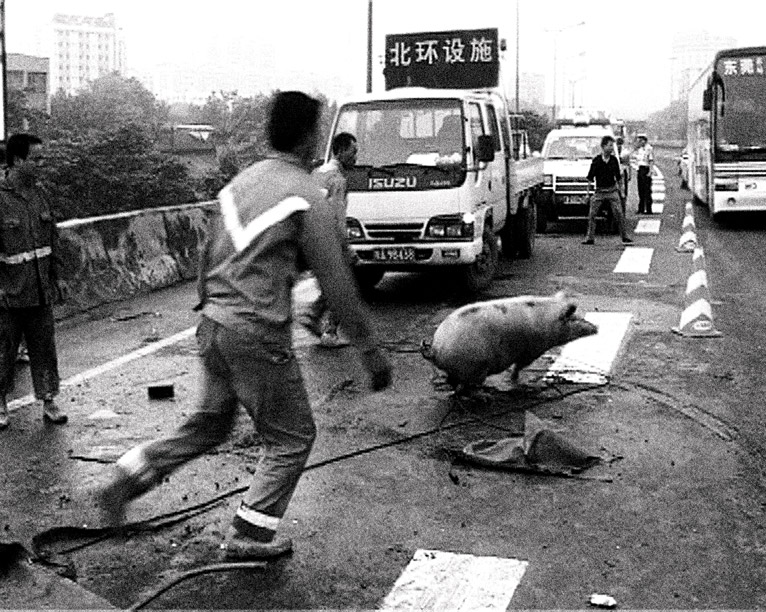

Disorder goes on to weave together a tapestry of bizarre occurrences in the city, culminating in a chaotic final sequenceof seemingly random acts of police brutality in a public space that has erupted into riots. In the film, Huang Weikai assembles a hodgepodge of fractured narratives and strange events. We see a vagrant dancing ecstatically in the street, shady dealings in bear paws and anteater parts, a maniac threatening suicide on a bridge. Huang’s editing presents these sequences as fragments that the audience can never fully grasp, like hallucinations surfacing in the liminal space between dream and reality. We are also presented with scenes of a lone fisherman retrieving objects from the stagnant filth of an urban cesspool, a cockroach crisis in a noodle shop, traffic police scrambling after a truckload of escaped pigs running wildly on the highway. The images and sounds of the city push the thresholds of documentary realism, and the film becomes a kind of surrealist urban ethnography, blending the sounds of the city with found footage to create a disorienting digital collage of life in Guangzhou.

The events represented in the film seem to reflect a form of urban possession, an abstract power of the city over its inhabitants, who attempt to confront and grapple with the absurd events that unfold in the lived experience of the everyday. In Disorder, we witness possession on multiple registers—the possession of individuals under the gaze of a DV camera, and the possession of both director and subject under the spell of the city. Through the reconfiguration and recontextualization of “found objects,” or found footage in the case of Huang Weikai’s project, he introduces jarring juxtapositions that subvert audience identification, often leaving the viewer bewildered, disoriented, powerless and confused. The film’s raw, grainy DV quality and its radical leaps from fragment to fragment are aesthetically mesmerizing. It distills a number of the qualities that Walter Benjamin locates in the practices of the surrealists, particularly the blurring of waking and dreaming states, and the interpenetration of image and language to yield a system of unstable meanings. As Benjamin writes in The Arcades Project, “And no face is surrealistic to the same degree as the true face of a city.” As Disorder exposes the underbelly of the city, making visible the absurd occurrences that are often subordinated to the realm of the invisible, his film offers a provocative portrait of an overwhelmingly absurd urban experience.

Huang Weikai’s next project will turn the gaze of the camera onto his own kind: the independent documentary filmmakers who capture the rhythms of urban China with DV cams. Though he has yet to begin filming, his next work will be a narrative film called Documentary, once again set in Guangzhou, but this time in the cramped space of a shop selling pirated DVDs, where his protagonists, a cinephile DVD storeowner and his DV documentarian friend talk the classics and plot grand schemes for the feature films they hope to one day shoot.

While the project will follow the general conventions of narrative filmmaking, Huang’s concept did not arise out of a desire to switch cinematic forms: “I’m not making a narrative film per se, but tracing the development of the independent documentary in China. I want to produce a work that displays the core of the independent documentary as a form.” Documentary also promises to reveal reflexivity and self-consciousness. Huang clearly states the intentions of his project and how it connects to a larger discourse of independent documentary production to which he is inextricably linked: “A lot of my friends and other independent documentary filmmakers in China were not formally trained (they’re not graduates of the film academies), they simply love movies and decided to pick up DV cameras to make films—one person can make a film.”

Huang Weikai’s documentary aesthetics, particularly those at work in Disorder, reveal new directions in a field of documentary filmmaking that has become saturated with dry character studies and self-indulgently long, roughly edited films. His surrealist digital collage points to how the fleeting realities pursued by documentary filmmakers have become unstable, absurd, and fragmented. His concern with urban space and the position of the individual in the city strikes a chord with larger social phenomena that must be confronted when we consider the state of China’s booming metropolitan centers. Furthermore, his solidarity with filmmakers working on the periphery gives his works an elevated sense of vitality, which materializes as a penetrating point of social intervention. We’ll just have to see what emerges on Huang’s next digital canvas with Documentary.