THE EIGHTH SHANGHAI BIENNALE: REHEARSAL

| December 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 6

If liberal-mindedness was the legacy of the groundbreaking edition of the Shanghai Biennale titled “Shanghai Spirit” in 2000, then in 2010, “Rehearsal” represents a tentative step in the direction of reflexivity. Though the word “Rehearsal” does not connote much on its own, we can extract from a reading of the exhibition’s expository texts a posture of profound reflection upon the whole of contemporary art and the cultural and ideological systems behind it.

With a particular focus on the avant-garde proposition of “art’s intervention into society” (to borrow the title of Wang Chunchen’s recent book), “Rehearsal” invokes Bertolt Brecht in reflecting on the politically effective dimension of art: “actors in rehearsal do not wish to ‘realize’ an idea. Their task is to awaken and organize the creativity of the other. Rehearsals are experiments, aiming to explore the many possibilities of here and now. The rehearser’s task is to expose all stereotyped, clichéd, and habitual solutions.” And art here is meant to be understood in terms of society, as one of its component parts. From this perspective, societal reform cannot happen until reform takes place within art itself. In more concrete terms: the spirit of experimentation must be maintained. This is art’s true political charge.

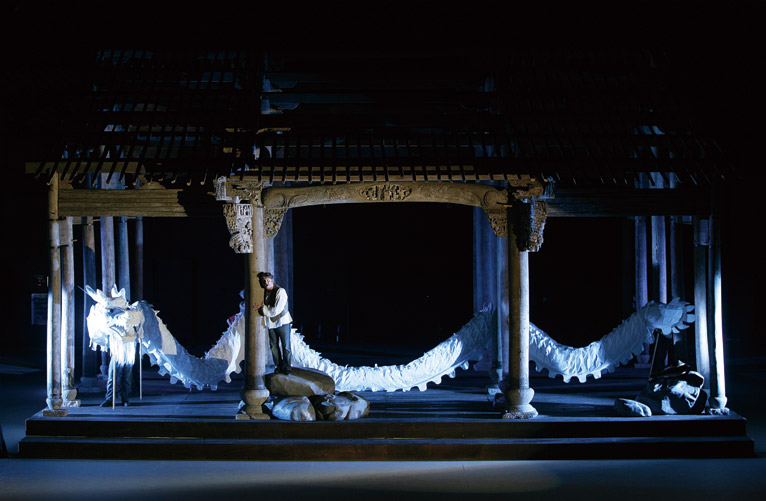

However much the exhibition texts stress this theme, not all of the artists or works exhibited conform to it. Or more accurately put: not all of the works have been included on such purely curatorial grounds—a fact that, unfortunately, is especially glaring in light of the boldness with which the exhibition exposits its academic premise. On the first floor, the stereotypical, clichéd, and habitual concept behind Zhang Huan’s ancestral temple—though it does come literally from the theatre, as the set of Zhang’s recent production of Handel’s Semele—represents exactly what Brecht opposed. The choice to import ready-made objects not only demonstrates a lack of innovation, calling to mind Chen Qiulin’s moving an old house into the Long March space back in 2006. It also fails to produce any discernible dimension of meaning or feeling; in the scope of the entire exhibition, it is but a transparent flourish. Even worse, Mu Boyan’s sculpture, Fatty, has been sluggishly stationed by the second floor entrance in what seems to be the result of last-minute cramming. Hsia Yan’s metal handicrafts at the end of the third floor gallery are also a somewhat puzzling choice, unless one knows that this senior Taiwanese artist has donated works to the Shanghai Art Museum in the past. Protrusive spectacles such as these leave us no choice but to lament the difficulties confronted by a curatorial system lodged within a bureaucratic system as it attempts to see a concept through from birth to implementation.

Despite some blemishes, there is also no shortage of excellence and appeal. The most striking work comes from the Norwegian collective Verdenstreatret; they integrate machinery, installation, visual and aural experience, music, and performance, forcing their audience to confront total uncertainty and arousing innumerable sensations with

a complex, fluid structure. Every aspect of Qiu Zhijie’s room-sized installation invites curiosity as well, though it still comes with some intellectual and ideational deficiencies. At any rate, catching the eye of the audience is a feat that can occur on two levels; something like Ma Liang’s studio is sufficiently eye-catching: it is the kind of work that one does not need to get to the bottom of to understand. Whereas French artist JR’s huge black and white photo prints – scattered across the exhibition hall and the city – are not only eye-catching but also able to inspire the audience to continue to explore. This is not to say that people go from city wall to city wall in search of more of JR’s images; it is to say that his approach is direct and concise, and that he does more than merely construct a visual spectacle for his audience. Jun Nguyen-Hatsushiba’s video of himself running repeatedly is a little bit surprising: it is extremely simplistic—almost a thumbnail in comparison to the epic underwater images everyone so vividly remembers from his earlier work. Yang Fudong, continuing along the lines of the polyphonic images from his 2009 Zendai solo show, has not surprised anyone with his current work, though its unfinished quality does possess a certain “theatricality” and thus conforms to the theme of the exhibition.

Altogether, the works belonging to the exhibition’s “Ho Chi Minh Trail” section on the first floor comprises the core of the exhibition; since the original “rehearsal” exhibition brought these artists together at Long March Space earlier this fall, it has amassed new references and has had sufficient time to brew and mature. The works have more fully assumed a creative dimension inspired by reflection upon the politico-artistic; MadeIn and Wu Shanzhuan in particular have developed a sphere of thought consistent with this new outlook. MadeIn’s linguistic wit may come across as a little bit over the top, or rather, overly strategic—but then again, MadeIn itself is a strategy. Then there is Liu Wei’s installation: as compared with the piece shown in the Long March Space exhibition, it has to a large degree lost the force of “wildness” that its material and space originally possessed—it seems to have been tamed somehow. This is perhaps a result of the art museum’s strict regulations, or otherwise of a preemptive interpretation of what “art museum” means in practice. Most mind-boggling is Zhang Hui’s work, which might be referred to as “auteur painting” (to borrow a concept from film). In contrast, Liu Xiaodong’s images of Sichuan earthquake survivors hung beside these might be described as “project-based painting.” One paints in self-contained meditation; the other produces openly and casually.

Whether it be public museums lacking a true public commitment, interest-based calculations based on underworld relations, artists as celebrities, or the increasingly enormous, yet increasingly proficient system itself, the new ills of society come as no surprise to anyone. China’s biennials must face these realities as they grow into maturity; one might even go as far as to say that only upon internalizing their imposed restrictions and regarding them as working conditions is an artist free to create. Creation is almost always subject to constraints; the key for the artist lies in whether and how he or she is able to sufficiently distill those constraints away. Bao Dong