DAVID DIAO

| March 22, 2011 | Post In LEAP 7

At once meticulous and good-humored, David Diao’s twelve boldly colored canvases on view in Antwerp presented a succinct midcareer synopsis, bookended by references to the American painter Robert Motherwell. The works on view date from 1986 through 2010, beginning with two excerpts from Diao’s mid-1980s “Little Suprematist Prisons” series, whose hard-edged geometric compositions stage an entrapment of Constructivist elements behind vertical yellow bands lifted from Motherwell’s Little Spanish Prison (1941-44). Performing a confrontation of art-historical trajectories, these paintings marked a period of release for Diao from his own acute impasse behind the constraints of end-game formalism.

Born in Chengdu, Sichuan province in 1943, David Diao fled China with his paternal grandparents in 1949, later joining his father in New York at the age of twelve. In 1969 he first gained visibility as an artist with an exhibition of plaster-joined sheet-rock panels at the Paula Cooper gallery. By 1978 a detail of his work had appeared on the cover of Artforum, and yet in 1980 Diao temporarily ceased production due to a crisis in his practice as an artist in general, and as a painter in particular. While the (Manhattan) art-world spotlight trundled on towards various forms of expanded practice, Diao returned to the painted plane in 1984, undertaking to “work among the remnants,” as he has put it.

The elegantly choreographed showing of over two decades’ worth of work within this mode reveals an artist busy with rigorous reference to art history and its discontents. Alexander Rodchenko, Kasimir Malevich, Henri Matisse, Philip Johnson and MoMA all come up for comment, rendered as a palimpsest of glyphs and diagrammatics dancing across fastidiously prepared monochromes. The good-natured if incisive humor within the references to both Rodchenko and the artist’s own biography in the upward-slanting graph line of Five Year Plan (1991), or the faux MoMA invitation card depicted in The Board of Trustees (1994) bespeak a savvy for historical and institutional critique that falls delightfully short of cloying. The white text of Imperiled (2000) floated in a field of yellow—a punning reference to an earlier moment of China paranoia, the nineteenth-century “Yellow Peril”—demonstrates how his particular brand of painting-about-painting can touch simultaneously on questions of racial identity and formal language.

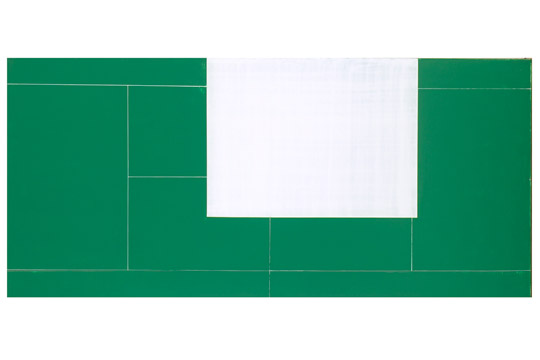

Hung according to visual and symbolic rhythm rather than chronology, a study of the canvases by date reveals the increasingly personal presence of David Diao within the frame. One of the most recent works on show, Open/Surrender (2010) extends the artist’s investigations into the demolished family compound of his childhood, of which a tennis court provides the only concretely knowable dimensions. (This reimagined home was the subject of his “Da Hen Li House Cycle” shown in Beijing in 2008.) As a green monochrome marked with the lines of a tennis-court and overlaid with a white rectangle, Open/Surrender simultaneously calls to bear the white flag of submission and the late-career “Open” paintings of Motherwell. The dense resonance within this painting is made all the more poignant by the fact of Diao’s father’s death on the site of a Long Island tennis court.

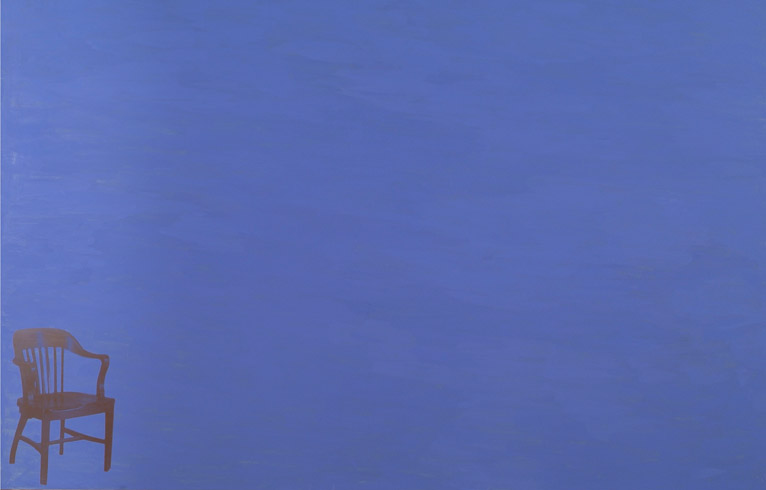

The broad view provided by the exhibition makes apparent a certain honesty in David Diao’s adherence to painting, at the core of which lies the human truth of pleasure. Common among the canvases is a delight in the viscous application of color to surface. A work such as For Scale Sake (2010) conflates conceptual abstraction with the downright scopophilic, luxuriating in the exuberance of a blue within which one can swim. In another nod to Motherwell, the screen-printed seat in the bottom-left corner of the canvas references the manner in which the American artist’s paintings were exhibited in close proximity to a chair, placing them in relation to human proportions. It is similarly through the insertion of the human scale in the guises of humor, pleasure and the contingency of biography, that Diao’s paintings maintain a critical project from within the practice of painting. Vivian Ziherl