LU YANG: MAN AS ANIMAL

| October 10, 2011 | Post In LEAP 10

One need look no further than de Sade’s salacious masterpiece Justine (1791) to see that his philosophy posits God as a mercilessly evil being. In it, the hapless twelve-yearold protagonist naïvely places faith in the virtuous magnanimity of strangers, all of whom end up either raping, beating, robbing, or otherwise enslaving her. Morality thus bows down to Mother Nature, to the bare-knuckled compulsions that at once serve as orgasmic respite from toil and human suffering and, more elementally, to guarantee the continued survival of our species. It is this definition of control— in the broadest, most animalistic sense of the term— that informs much of the work of Shanghai-based new media artist Lu Yang.

Her art has been called cybernetic— essentially, physiological hacking, whereby machine controls animal— in an interpretation that at least nominally adheres to her recently obtained Master’s degree in new media Art from the China Academy of Art. In Hangzhou, she discovered the nascent field of “BioArt”, in which she finds most currency. Her most recent (perhaps awkwardly titled) solo exhibition “KRAFTTREMOR: The Project of KRAFTTREMOR” at Boers-Li Gallery was based entirely on the “contemporary phenomenon” of Parkinson’s disease. One neon-heavy science-fictionesque print appropriates her own image as a DJ who orchestrates not dance music but the neural processes of four helpless male Parkinson’s patients (the aged godfathers of electronic music, Kraftwerk, or with a bit of imagination, the aged protagonists of The 120 Days of Sodom) by way of electromyography, eye tracking, and electroencephalography. The manipulation amounts to insult to injury; impotence is a common symptom of the disease. Another work in the show is a mesmerizingly unsettling video installation produced entirely by the artist herself— haunting synthetic soundtrack included— for which she asked to film Parkinson’s patients from hospitals across the country (those willing to be filmed are few and far between, and families often cite ethical reasons in their refusal) while they struggled to exercise basic motor skills. Reliant on the cold precision of computer technology, the exhibited artworks reveal visceral incisions of the pulsating veins of power, ethics, and desire.

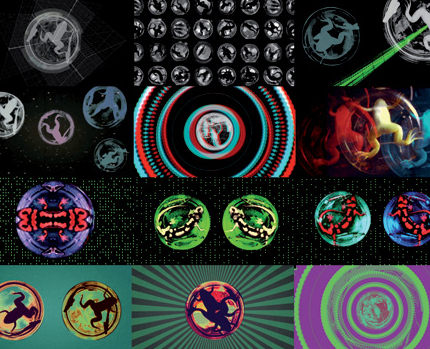

Much like the stoically masochistic fetishism central to de Sade’s life and work, several of Lu’s earlier works come off as the ruthless experiments of a mad scientist, albeit with an overtly calculated execution that injects the artworks with an even heavier does of the grotesque. For the installation Happy Tree and the progenitive Dictator E, Lu classified various amphibians according to species and placed them into water-filled glass containers, using electric currents to stimulate their movement underwater; corresponding sound frequencies were amplified, and the involuntary “dance” of these pathetic creatures was magnified in high-definition video— a formal precursor to the KRAFTTREMOR music video, in which the patients’ eyes were altered to resemble those of amphibians.

For this installation and her other works of BioArt— not products of Lu Yang’s imagination but rather, “accumulations of theoretical knowledge”— the artist relies on the assistance of scientists and psychologists to ensure factual and methodological accuracy, as well as to avoid crossing certain ethical boundaries— Lu has stated that the first time she exhibited Happy Tree will also be the last time. Just as well, it could be that Lu is uncomfortable with the divine role she has created for herself: a simultaneous belief in and mistrust of religion (she was raised a Buddhist) runs through many of her creations, channeled through an uncompromising embrace of the physiological rhythms of human existence. Science, too, for all the power it grants her as an artist, is an object of suspicion; that which possesses such God-like potential is just as dubitable as the very advocacy of God.

De Sade held that vice— or the pleasures of the imagination— should not be punishable by law. Vivid are the threads of this libertinism in Lu Yang’s series of cut-out “instruction manuals,” which include Do it Yourself! Pervert Crime—Coprophagia; How to DIY your own Sanitary Towel Respirator; and How to kill a part of your body—DIY nipple breaking-off. In each piece, viewers are taught sexually ambiguous “activities,” the objectives of each rather self-evident. Under “normal” circumstances— i.e. in private, watching on our computer screens— these activities are bearable, if not pleasurable, for the voluntary viewer. Yet by suggesting a kind of educational benefit of what the viewer is “learning,” what Lu Yang does is almost the impossible, that is, to render fecal fetishism and self-mutilation even more grotesque. Once again, the discussion here could turn to the rules of control: DIY grants us with a means of “safely” containing the animal urges that may otherwise compromise our place in society (or our lives; see Safe Suffocation DIY). Control here is also present in Lu’s subversion of conventional spectatorship—with a futuristically flashy sleight of software, she slyly steers viewer reactions towards discomfort and disgust— especially in the arena of Chinese contemporary art, where artistic practice rarely speaks so dirty to its audience. Or so cruelly: similar praise could be given to Happy Tree. Much worse takes place behind the closed doors of the pharmaceutical and meat industries, but no matter how many animals we eat or pills we take, few stop to think, let alone care, about any of that.

Lu Yang’s working methods provoke rage, criticism, and on one occasion, even censorship. Indecency and animal abuse are most often cited in these objections, but what lurks behind them may just as well be viewers’ perturbation with her equation of man to animal, or even worse, to nonmammal— or machine, as in the case of her recent probing into Parkinson’s, which may or may not have aesthetic and/ or conceptual bearings in Japanese entertainment culture (see Masamune Shirow’s seminal manga Ghost in the Shell, broken doll AV, J-pop music videos, et al.). This sort of hypothesizing is less speculative than the notion that de Sade acted as mentor to Lu; she is, after all, a self-proclaimed Japanophile with a long-running fascination with her easterly neighbor. Happily, she will take up her first residency abroad at the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum this summer. Here’s to wondering how her work will be received in Japan, where— at least, to outsiders— de Sade, Buddhism, and technology fit right in.