LUIS CHAN: A STRANGE LITTLE ISLAND

| November 28, 2011 | Post In LEAP 11

LUIS CHAN WAS born in Panama in 1905, moved to Hong Kong in 1910, and stayed there until his death in 1995. His artistic career spans nearly the entire twentieth century, and he is widely regarded as Hong Kong’s pioneer of modern art. He never received formal art training, but he showed an early interest in painting. After finishing middle school (in the 1920s this was considered sufficient formal education), he worked as a typist for a lawyer during the day, spending his nights painting and his time off in the countryside painting from nature. He was also keenly interested in the typeface used in the headlines in the South China Morning Post, often trying his own hand at designing fonts just for fun. His friend and fellow artist Wang Shaoling was working at an advertising firm at the time, and Wang recommended Chan to a ferryboat company, where Chan made extra money designing fonts. At the end of the 1920s, he took a correspondence course from the Press Art School in London (he would receive instruction materials and then send works to England for grading, without ever having to go there). The first exhibition of his works was held in Hong Kong’s Gloucester Tower in 1935.

Luis Chan’s thirst for information about art was insatiable, as was his desire to master English. He liked to subscribe to lots of foreign art magazines, so he quickly became familiar with the latest trends in the American and European art worlds. Among the many artists who influenced his work, he claimed the Scottish watercolorist William Russell Flint and contemporary artists Helen Frankenthaler and William de Kooning were the most important. Indeed, Chan shared with them one particular trait: a strong focus on color. Despite his thorough Westernization, Chan had still never been to Europe; for all the modern Western art he had seen in publications, he had yet to see a single work in person. I also suspect that he hardly concerned himself with the background from which the various styles in modern art had emerged, nor their cultural constitution. The influence he received from modern art was indirect and fragmented, and to some extent this accounts for the freedom and frivolity of his experimental period. Underneath their superficial modernist pastiche, at a deeper level, his works exude a distinctive ambiance.

Luis Chan’s status in the Hong Kong art world was extremely high. Everyone knew him as playful, passionate, affable and completely unpretentious. He had the refined air of a wealthy upbringing and he spoke fluent English. His social circles had no lack of distinguished society, and he was friends with Western painters as well as traditional Chinese artists. He was passionate about film, music, dance, and parties. He liked to go to teahouses, eat dinner at snack stalls on the street, and play mahjongg.

In the 1930s and 40s, he had a fondness for painting realist watercolor landscapes. The technical skill of these naturebased works was supposedly extraordinary, and he earned a reputation as the “King of Watercolor.” Chan, Li Bing and Yu Ben, who had studied in Canada, together became known as the “Three Musketeers” of Hong Kong’s Western art world. In 1934, he joined Hong Kong’s preeminent non-Chinese art society, the Hong Kong Art Club, at which time he recorded the following event: “Although [the Hong Kong Art Club’s] monthly meetings are not open to the public, they do not prevent outsiders from participating. There is an immaculately dressed, high-society-type foreigner who regularly comes to look at paintings. At one of the meetings, this foreign gentleman turned up and, after learning that I was showing my work, asked me a great deal about painting. Everyone talked and got along extremely well. After the gentleman left, other members of our organization told me that he was Sir Andrew Caldecott, the governor of Hong Kong. Afterward, Sir Caldecott asked me to send him some paintings. Of the 30 I sent, he chose four paying 45 or 50 dollars for each. I was beside myself with joy because at that time, Xu Beihong’s paintings were going for roughly 35-45 dollars each.”

During the 1950s, Luis Chan set up his own studio and began offering classes. He also became the chairman of the Hong Kong Art Society and began giving art classes every Thursday in the main meeting hall. In 1960 he founded the Chinese Contemporary Artists’ Guild, emphasizing his hopes for the successful union of “Chinese” artists and “contemporary art.” Other than painting, he also authored many reviews and essays on painting. His writings touched on a variety of topics, such as An Introduction to Chinese Painting (1954), The Art of Sketching (1955), Lessons in Watercolor (1959), English Language Art Lettering Copybook (1961), and The Evolution of Paintings in the Twentieth Century (1965), among others.

In 1962, the new Hong Kong City Hall was completed, and the art gallery it housed (the predecessor of today’s Hong Kong Museum of Art) hosted its first exhibition, titled “Hong Kong Art Today.” There was an open call for submissions, but surprisingly, not a single one of Luis Chan’s famous works was selected, and most of the works submitted by Chinese Contemporary Artists’ Guild members were also overlooked. The selection process drew heavy criticism, raising questions on the identity of selection committee members, and on why the selection process had not been made public from the beginning. But organizer representative John Warner pointed out in his introduction to the exhibition that any “watercolors of the British School” or works either “similar to color photography” or done by “painters of the Impressionist school” were entirely unsuitable for selection. And yet during the early 1950s, Chan had already begun to experiment with various styles from the modernist movement, and the works he had entered for the exhibition were abstract. In the end, there is no way to know whether those on the selection committee believed his new style of art imitated foreign modern styles too excessively. In any case, this incident was the low point of his artistic career— but it was also a turning point.

Fortunately, at the time the Alliance Française was sponsoring an exhibition of the French artist Jacques Halpern, whose monochrome prints profoundly inspired Chan. The monochrome printmaking process occasionally leads to unintended textures, lines, or figures on the paper, which Chan began to employ in his paintings. Utilizing their spontaneity and unintentionality, he sought to achieve an odd effect— the bizarre and fantastic world the painter seeks. From then on, Chan always employed this method in his paintings, believing that he could arouse the fullest power of the imagination this way, and that the possibilities of what could be produced in this way were endless.

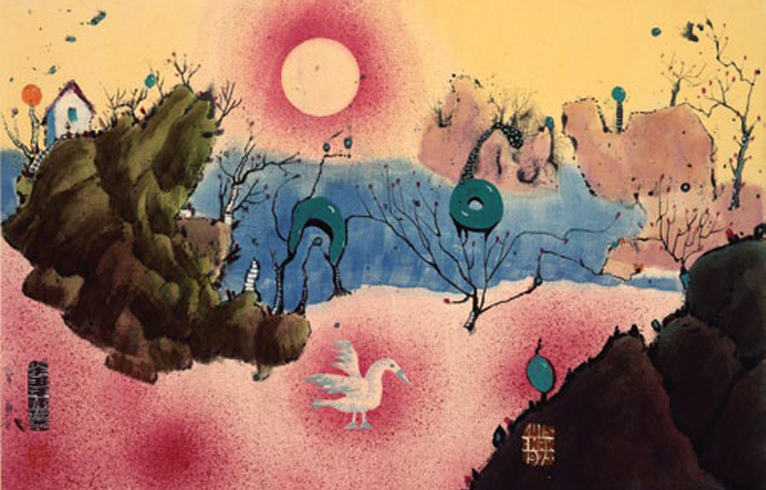

More than anything, Luis Chan emphasized the idea that creation cannot be stifled; he was constantly experimenting in his art. From the 1960s onward, he gradually began to integrate his capacity for realism and observation in his early years with modernist, non-figurative, unclassifiable techniques. Together with what the effect printmaking had had on him, he came to create a species of “fantasy painting.” I believe Chan never stopped in his progression. His later works are the most brilliant of his career.

Even though some of his works are purely abstract, Luis Chan’s emphasis was more on imagination’s vision of art than on pure spirituality, a kind of vision found in the work of great masters like Cézanne and Zhang Daqian. At times Chan’s paintings are brimming with humor and endearing imagination; at other times they can appear ugly, like a savage human face— a philistine’s observations of life, a microcosm of the myriad conditions of the mundane world. His “fantasia paintings” make heavy use of primary colors; the dazzlingly bold hues, together with strange scenery and characters, always making me think of the hazy, yellow submarine-style art of the hippies in the 1960s.

Again, Luis Chan’s paintings clearly draw from a variety of schools and artists. As David Clarke commented, “In one of his works, which is definitely intended as a dialogue with Lui Shou-kwan’s Zhuangzi, Luis Chan used collage (he used only real butterflies) and clearly pulled from Pollock’s splatter technique. This kind of splatter technique can also be seen in Chan’s other works, yet it is with a certain reckless attitude that he Chan uses it, having no scruples about the significance of the technique’s original context.”

As for the apparent collision of Eastern and Western styles in his art, Luis Chan did not adhere to such distinctions. As a result of the truly remarkable watercolors he did in his early years, Chan was seen as a Western painter of Chinese ethnicity. However, even though many of his works following the 1960s were created using traditional Chinese painting styles, their content and technique still predominantly resembled the Western modernist school. As for whether these paintings should be called Western or traditional Chinese paintings, Chan did not seem terribly interested in resolving the question of whether these paintings should be called Western or Chinese. He said that as long as the works bore the metaphorical Chinese red stamp of approval, then they were traditional Chinese paintings; those without the stamp were not. There was nothing serious about it. He followed traditional Chinese painting styles in terms of composition, which was very likely the result of his association with traditional Chinese painters (including important members of the New Ink Painting Movement). However, this question of Eastern vs. Western medium was absolutely not an issue for Chan.

John Clark regarded Luis Chan and Lui Shou-kwan as the two artists who had achieved the most success “communicating notions of modernist art to Hong Kong and defining how they might be transformed with Hong Kong subjects.” My thinking is that these are the two most important figures in the history of modern art in Hong Kong. Unlike Lui, Chan never sought to lead a movement, and with the passage of time no followers bearing his influence have emerged. Also unlike Lui Shou-kwan, he had no mission to reinvigorate cultural tradition. In reality, Chan was not a scholar in the traditional Chinese sense, nor was he an intellectual artist in the Western sense; his influences did not come from literature, philosophy, or politics, but from the little things in life, from the streets, from local people, and from television programs.

Fish often appear drifting in midair Luis Chan’s paintings, calling to mind Bada Shanren, but their origin is more explicit: not far from his Wanchai studio there was a place called the New Asian Strange Fish Restaurant, whose specialty was “strange fish.” Outside the restaurant there was a large fish tank with seafood on display, and there was also a mural featuring all kinds of fish. Chan liked fish, plain and simple. In his later years he used to go to a local shop that sold fish and look at all the peculiar species on display.

Early on, Luis Chan made frequent trips to the countryside to do landscape paintings. Gradually, he painted less and less of these until television became his primary subject. He was a huge fan of television: he would watch until dawn when the television stations stopped broadcasting, and only then start to paint. It was possible for any image from television to appear in his paintings, which probably accounts for the bizarre appearance in his paintings of such figures as Middle Easterners, Africans, people from Yunnan, the Pope, Yassir Arafat, the Queen of England, Qu Yuan, leopards, and elephants.

As for the spirituality of art, Luis Chan did not discuss this much. He was blunt about not believing in art’s ability to improve things or change people, and it is well known that he did not care about fame or fortune, so for him painting was simply something that captivated; in essence, there was no distinction between painting and other things he liked to do, like watch television, or play mahjongg. To Chan, art was always purely a hobby, a kind of pastime to which he attached no serious value, a way to eliminate worry, and nourish the soul. Chan said he liked art “the same way some people like to play video games.” He did not mean to downplay the essence of art, but rather to emphasize that art should always bring about a sense of joy.

No matter whether to a Western or a Chinese audience, nearly all of Luis Chan’s paintings have the mystical, illusory quality of a foreign place. But to true Hong Kongers, they possess a familiarity that is as aesthetically pleasing as it is difficult to articulate. Chan’s paintings, with their strange mix of culture and intersection of city and nature, certainly represent a kind of “Hong Kongness.” But it is crucial that we also remember how wonderful and charming his art is, and that he was not limited to a particular school of art but instead was in eternal pursuit of the spirit of innovation. This roughly represents the strange little island that is Hong Kong: its history is brief but exceptional, and it has neither the inheritance nor the burden of a cultural legacy; to create without cease— and excel at this creation— is thus imperative. Wucius Wong once said, “Hong Kong artists cannot talk of revolution, for revolution’s goal is the destruction of major obstacles, and Hong Kong originally had nothing (not even its own history or traditions). Therefore, we can only build.” It is my belief that Chan was a true founding father of modern art in Hong Kong.