A RESURRECTION OF IDEALS

| March 13, 2012 | Post In LEAP 13

WHEN ONE SPEAKS of the strong presence the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute (SFAI) has established within the Chinese contemporary art world, it is often in conjunction with the stream of painters who have emerged from it over the past 30 years. Consequently, in the eyes of many, SFAI is a breeding ground for painters who will later enter the Chinese art industry, Huangjueping being the place where these young painters experience their first shift of perspective. Today, the giant smokestacks no longer guide workers to the power plant; instead, the strange “graffiti street” guides visitors to the academy. These pragmatic guests unwittingly ignore the great changes this area has seen, the majority of them much more concerned about finding the place that is so important to Chinese painting.

To some, the SFAI painting tradition deserves heroic status, but to others who have spent time in Huangjueping, it is little more than a noose around the area’s neck. Meanwhile, the focus the outside world places on it engenders a double predicament for the Chongqing contemporary art scene. The always quite conservative, slow-to-respond education system of SFAI shows little sign of changing, while the art market continues to indulge in the great influence it has had. The result is that the contemporary art scene in Chongqing is prevented from confronting its own tradition, from breaking out and constructing a new contemporary art system. Although Huangjueping holds pretty much all of Chongqing’s artistic resources, apart from several clusters of artist studios, there are only two places which hold regular exhibitions at present: Organhaus Art Space, located in the 501 Art Warehouse, and Chongqing Art Museum, which is within the academy grounds. This state of affairs has persisted now for many years.

Limited funding and resources leaves artists with few opportunities to exhibit in these spaces, which in turn prevents the development of a consistent exhibition program, something that would stimulate local art practice, even on a daily basis. Although the art system of Mainland China now offers increasingly better opportunities for artists, the young people who graduate from SFAI with the desire to become professional artists have already begun escaping to Chengdu, or further afield to Shanghai or Beijing. Apart from members of the wider painting community, those who work in other mediums leave and are rarely seen again. Needless to say, the diverse foundations on which a future art ecology could thrive are not being laid. In fact, a kind of art-ecological “Matthew effect” has become a real issue for experimental art in Chongqing.

There have been attempts to remedy the situation: in 2005, Li Yong, a representative figure for Chongqing experimental art, set up an independent space called H2 together with Bao Dong, Ni Kun, Wang Jun, Ge Lei, and others. Although its sign still hangs at the entrance of a space on the ground floor of 501 Art Warehouse, this project lasted only about a year and six exhibitions before falling into inactivity. But for Li, the motive to set up his own space was linked to a recent personal experience.

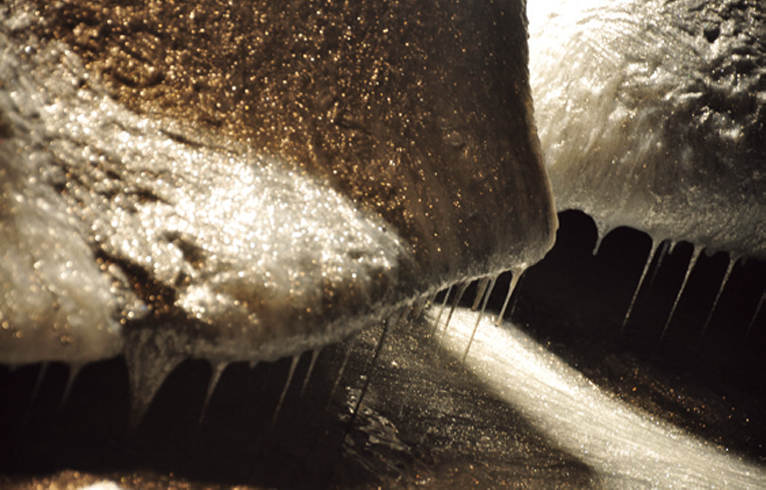

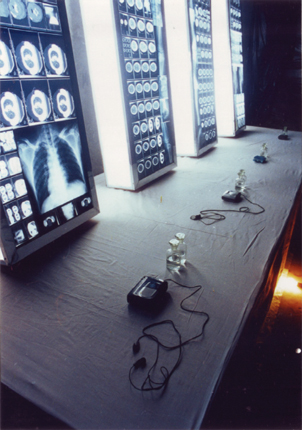

Freshly graduated from the print department of SFAI, in the year 2000 Li Yong organized an experimental art show titled “Aphasia” with fellow graduates Huang Kui, Li Pinghu, Li Chuan, Ma Jie, and others. Despairing at the academy system, the group decided to leave Huangjueping and find a space elsewhere in Chongqing to hold the exhibition. After much difficulty, the group finally opened the show in a real estate sales office in Shapingba district. The opening of “Aphasia” happened to coincide with the second peak of experimentation in Chinese art since the ’85 New Wave that was spreading fast across the country and starting to be “officially” taken seriously by the Shanghai Biennale. Things seemed to be moving in a positive direction, and “Aphasia” received an unanticipated amount of attention, even from SFAI itself— an institution with a long-standing coldness towards experimental approaches to art. Owing to this nascent experimental group, new forms of art began to flourish in Chongqing amongst increasing numbers of young students. For almost every exhibition, however, a new temporary space had to be sought; the 2004 show “Cave,” for example, was held in an air raid shelter located in Huangjueping. It could be said that the autonomous nature of H2 was the result of the irritated reaction of a group of curators and artists to the poverty of Chongqing’s art spaces.

To be sure, the disappearance of H2 did not come out of nowhere. True, Bao Dong left for Shanghai in 2006, and H2 closed shortly after his departure, but this should not be taken as a simple case of cause and effect. As the most active young curator in Huangjueping at the time, Bao’s work, both curatorial and critical, came to be regarded as the initial drive and enduring source of energy of Chongqing’s experimental art community. Looking back today, regardless if at his critique of a new cartoon phenomenon formulated in Chongqing, or at the group exhibition he curated at Chongqing Art Museum in 2006, titled “Re-metaphorized Reality,” all were instituted in response to a personal preoccupation with structural linguistics.

Incidentally, Bao Dong’s departure coincided with the boom of the Chinese contemporary art market. As Huangjueping’s workspaces were welcoming a constant stream of keen gallerists, a certain group were seriously concerned by a certain individual’s departure, forced to face up to the imminent disintegration of their community: the market never takes groups, but individuals. Bao’s departure, much like that of Chu Yun, Huang Kui, Li Pinghu, and others before him, simply acted as yet another reminder of the disease that was afflicting the art ecology of Chongqing. In other words, H2 was swallowed up by the increasing ferocity of the Chinese contemporary art system.

At the time the entire system was seemingly retaliating against its former so-called deficiencies, Chongqing’s experimental artists went pragmatic, picked up paintbrushes and turned themselves into sensible artists. The unexpected breadth that comes with being a “professional artist” to a certain extent also threatened their inner sense of superiority; in the face of the market, everyone had become mere “Huang drifters.” Although this term has now faded out of the Chinese art market’s post-bubble vocabulary, the psychological impact it has had on the area remains. Nowadays, in most all studios there are painting works to be found, even if one occasionally does come across an artist willing to discuss his or her performance or installation work. But on a strictly professional level, being a painter at least seems more dignified than teaching SFAI hopefuls at cram school.

Comparatively speaking, the Huangjueping of today seems a little desolate. In one sense this is a result of the market’s influence, though another major reason is the move of several of the remaining departments of SFAI’s Huangjueping campus to the Huxi campus in Shapingba district. Although the local government has attempted to transform Huangjueping into a specialized art zone, or a “cultural creative industry park,” it has done little to give cause for optimism for the future beyond leasing the former industrial base’s empty warehouse space out to artists for studios. Organhaus Art Space, however, contrary to expectation, has remained in Huangjueping since its inception in 2006 and now appears to be a rare and valuable establishment, especially considering the increasingly grave state in which the Chongqing Art Museum has found itself since SFAI left the area. Indeed, the combination of these factors has turned Organhaus into a central creative hub never before seen in this area.

The origins of Organhaus can be traced back to M Commune, established in 2001. For a long time, M Commune was an important place of activity for experimental art in Chongqing, as well as a gathering space for a new generation of art youth. It often puts on experimental music concerts, film screenings, painting exhibitions, and various other cultural events. The person currently in charge at Organhaus is the same person who founded M Commune, Ni Kun (another founder was Pang Xuan). Today’s Organhaus continues this operational approach: far from focusing solely on exhibitions, its curators strive to maintain a diverse program— they have organized a festival of Chinese and international independent film, as well a series of artist workshops in 2008— and strong dialogue with the public.

That Organhaus has been able to exist in the long-term is due in part to the export-oriented strategy it has adopted. It is certainly the most international of all Chongqing art establishments, evident on the one hand in its funding. The space’s founder, Yang Shu, finances only rent, basic supplies, and the wages of two staff members, while the not inconsiderable remainder is drawn from overseas foundations and various foreign state-sponsored arts funds. Nonetheless, the quality of international exchange programs often depends on the level of the artists in exchange, a dependence that leads to instability. In operational terms, however, this system provides the opportunity for talented young Mainland artists to come to Chongqing on exchange, or even to take up residency overseas. By the time it was trendy to start keeping tabs on up-and-coming artists, the longstanding emphasis Organhaus had already placed on young artists ensured that the space would maintain its strong influence.

As an independent, non-profit organization, Organhaus keeps alive the artistic ideals of many of those who worked in Huangjueping long before it. With its collaboration with the newly-formed Ceiling Space (established in 2010), the embryo of a localized, composite contemporary art system may or may not have begun to take shape. Ceiling Space is situated within the famous Eling Park in the central Yuzhongqu district. Its primary investor, Zhou Yaxin, has always been an admirer and collector of contemporary art. Although his transformation into a gallerist was somewhat accidental, his open-minded attitude towards art, coupled with an astute knowledge of the local collector environment, means that the gallery has from the outset focused on cultivating its academic qualities. With Tian Meng acting as art director of the recent “Huangjueping’s Faust”— a series of exhibitions and events which took the corporeal experience of locality as its starting point— this space is drawing Chongqing experimental art into new discussions on cultural autonomy.

Working off of the dialectical relationship between epistemology and practice, “Huangjueping’s Faust” was divided into five components: “Ruins of the Subjective Imagination”; “The Sayings of Confucius”; “The Hormonal Age”; “The Post-Hormonal Age”; and “Utopian Delusions.” First entering into historical research and observation, then into the background of knowledge, then returning to the construct between the body and the present, the project placed its ultimate focus on individual and regional cultural autonomy. Never mind if the discussion of cultural autonomy is outmoded— it cannot be denied that thanks to strategic implementation, the Chongqing experimental art scene was once again revitalized in 2011. SFAI, although now far away from Huangjueping, remains an important source of support. More importantly, the principle awareness and reflective mechanism “Huangjueping’s Faust” has attempted to initiate is precisely what contemporary art can contribute towards overcoming the limitations of the individual.

Since the initial phase of Chongqing’s experimental art scene at the turn of the century, to its resurrection in 2012, Huangjueping has inevitably seen various changes. One person might point to a new teahouse, another might say the flavor of its dishes has changed. As far as experimental art is concerned, though, what has not changed is the local collective consciousness. Those on the outside may be quick to suggest that this is a case of artists sticking together, and those on the inside may very well respond that now is a good time to be doing just that.