BEIJING VOICE: LEAVING REALISM BEHIND

| March 12, 2012 | Post In LEAP 13

Even though the introduction to the exhibition states that the formalization of art and realism have been cautiously formulated as coexisting in relation to each other, there is still a strong whiff of something different from the verb in the English title of this exhibition. In the early 1950s, formalized art and realism in China experienced a similarly fierce conflict. The result was a victorious oppression of the former by the latter that lasted until the early 1980s, when internal debate on formal beauty caused the scales to tip for the first time. Consequently, it is easy to identify the context of the contradictory and suppressed feelings toward realism apparent in this exhibition.

Even so, in the context of contemporary art, realism by no means needs to be left behind. Just the opposite— it is actually at the core of global mainstream art practices today. From this starting point, the originally clear direction begins to seem subtle and ambiguous. In fact, in his densely concise foreword, curator Leng Lin sets out precisely to address this issue of subtlety. In China, seeking a totally new, legitimate discourse covering 30 years of the practice of contemporary art requires that realism be dealt with; in other places and countries, perhaps this issue is no longer being discussed. Whether to accept or reject realism is as intractable a problem as any. On the one hand, contemporary art is impossible to separate from reality. On the other, in China, realism is either appropriated for political propaganda or appears as the face of visualization and symbolization. Both forms of abuse already elicit our disgust to different degrees. This is the reason for the ever-increasing manipulation and revision of history in recent years. This exhibition must be added to the list of examples.

In order to generate an effective dialogue with contemporary art, what method, post-realism, is left? If we still want to retain realism as a relevant factor, then this method is undoubtedly neo-realist. Compared with many exhibitions that simply fall flat, “Beijing Voice” integrates important elements from modernist-based antimodernism. As a Chinese audience, we are thus fortunate to have the opportunity to seriously and profoundly confront our artistic tradition for the first time post-minimalism. Previously, a good number of people still regarded painting with modernist methods, even relying on point, line, plane and imagery of a painting to generate its meaning. A watershed for contemporary art, the minimalism of extreme materialization marked the end of that logic. It is through a systematic reappraisal of this period in art history that “Beijing Voice” seeks a new anchor for realism.

What “Beijing Voice” achieves— through a reflection and remolding of realism, and a revolt against modernism— is the ability to continue a dialogue with contemporary art. It is because of the very fact that form itself has been awakened within the narrative of realism that works narrowly defined as “abstract” or “formal” before were then emancipated from the ivory tower of pure aesthetics. The only thing that needs to be emphasized here is that the reality embodied by the exhibition is by no means due to the feeling of presence generated by its social involvement. On the contrary, the sensation of an urgent reality originates in the powerful claims brought forth by the abstract concept of cultural identity. In this sense, we may achieve a deeper understanding of why the curator, despite using a style devoid of emotion— as seen in the light art and hard-edge painting on hand— was still able to project and emphasize the principle subject of artistic creation: the concept of the self. As the logical extension of realism post-awakening, this subjectivity of the self happens to be the theoretical basis the curator found most feasible after coming to grips with contemporary art trends. By steadily manipulating and magnifying a collective idea of cultural subjectivity, the curator turns the reality posed by “Beijing Voice” into one of its particular strengths. This is the exhibition’s most significant goal.

The subject of this differentiation is intentionally set apart by the show’s exhibition’s layout. Entering through the door on the right, we see mostly works of American Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism, such as James Terrell’s Untitled (2007), Donald Judd’s Untitled (1988), Ad Reinhardt’s Abstract Painting, Blue (1952), Mark Rothko’s No. 1 (1957), and others. This sequence continues all the way to Chuck Close’s slightly numeric Self-Portrait (1996). Immediately prominent from the entrance on the left is Lee Ufan’s Dialogue (2007), whose intensely Eastern philosophical mentality indicates the strong Asian quality of this section of the exhibition hall.

If it would not be so disappointing to hear, we might say that were it not for their sensational reputation, the display of these Western artists’ works would honestly be nothing worth reporting. These works have generally been given a place in the loose genealogy of Western art history, but their placement seems to adhere to certain rules; here it seems little effort has been made to raise any new questions. Similarly, collating such an array of vastly different works via spiritual interpretation so as to achieve a kind of Western subjectivity is a method itself worthy of consideration. In the case of Rothko’s painting— even though the exhibition dispenses with Greenberg’s argument, only to return again to the cosmic philosophy of Rothko himself— the question is whether the work of Rothko, who possesses the subjective consciousness of the modernist tragic hero, can be placed on par with the subjectivity that developed following the minimalism of extreme materialization.

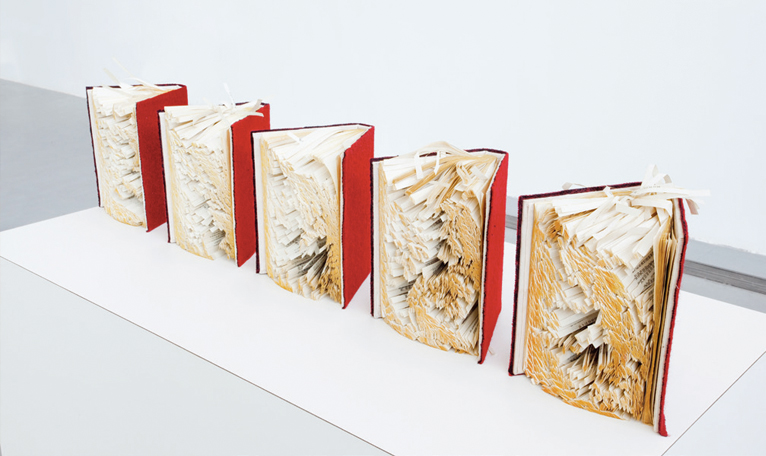

Fortunately, this rather lackluster display of artwork achieves a certain comic effect. Precisely because it is lacking, other subjects seem all the more prominent. We can see the philosophy of everyday objects in Song Dong using butter and books as the stuff of art, putting a very Eastern method into practice. Sui Jianguo once again abandons figurative technique, allowing for a more meditative and profound relationship with physical substances. Wang Guangle’s dizzying take on form, beyond his unique skill, is due at an even deeper level to his intimate connection with Chinese culture. On that note, Liu Jianhua chooses to work with ceramics, and Ding Yi’s works bear a heavy superficial resemblance to Chinese folk embroidery— different approaches that achieve similar results. Although the works of Li Songsong, Liang Yuanwei, and Xie Molin represent an interpretation of subjectivity on another level, taken as a whole, theirs is a cultural subjectivity realized subtly, be it through their choice of material or working method. This kind of subjectivity does not make understanding too difficult on us. Take, for example, the utilization of waste materials: in John Chamberlain and Liu Wei, we can detect two completely different cultural worlds.

In terms of promoting the particular trends of Chinese art, “Beijing Voice” is no more sophisticated than any other similar major exhibition of the past ten years. But through the display of Western works, especially from the Minimalists, this exhibition can perhaps spur China to start rethinking the locus of contemporary art, and to integrate our own understanding of contemporary art into a framework that previously was vague to the point of deficiency. Precisely due to its value as such a counterpoint, this exhibition achieves particular significance. Po Hung (Translated by Caly Moss)