CHANGE NOW, CHANGE LATER

| March 15, 2012 | Post In LEAP 13

INSIDE, OUTSIDE, AND PERIPHERAL

“NOW THAT WE’VE finished going through all of the traditional types of painting and the history of art in Hubei, we are definitely going to move in a more modern and contemporary direction.” As he speaks, Hubei Art Museum director Fu Zhongwang is sitting in the museum’s coffee shop, looking out through its glass windows towards sculpture works by Hubei artist Shi Jinsong. A little bit further on down, in the exhibition “Transfer,” the director’s own works— among them paintings, installations, and videos— are on display. For a newly opened provincial art museum like this one, an exhibition like this is quite contemporary indeed. The others are not quite as avant-garde: “The Xinhai Revolution,” “The Seal Carving, Calligraphy, and Drawings of Li Lanqing” (a former member of the Politburo Standing Committee), and “Picture Exhibition about Peking Opera and Hubei” [sic].

The Hubei Art Museum opened in November of 2007. Its opening exhibition, “Retrospect and Prospect,” traced the development of art in Hubei from the Republican Era to the present, featuring traditional Chinese paintings, oil paintings, engravings, and sculptures. It was a safe, conservative approach. In choosing to catalogue the development of Hubei’s art, the museum ducked any potential criticism, and— it must be said— its “2010 Hubei International Lacquer Triennial” did right by Hubei’s lacquer painting tradition. A strongly regional approach such as this, though, has obvious limits. As the museum’s director puts it, the exhibitions have to “satisfy our superiors, satisfy the experts, and satisfy the public.” With its fretting tone, this does not strike one as a particularly “contemporary” criterion for success. But it is a problem that provincial art museums such as this cannot help but confront. The museum relies on the government for its operating budget. Befitting its place within the system, its personnel structure resembles that of a state-run institution. But as both the museum’s existence and that structure indicate, the system has begun open the door to “contemporary” art— indeed, only two years after the Hubei Art Museum was founded, the similarly contemporary-thinking Wuhan Art Museum opened its doors to the public.

The government has realized what art can do for a city (though in China, the term “creative industries” may perhaps hold greater attraction than “art”). Its indifference towards art is a thing of the past. A glance at the exhibitions on display at the Hubei Art Museum is sufficient to know how this newfound interest has manifested itself. The size of the space gives one hope, though, and the task the new museum’s staff has undertaken requires patience and bravery in the extreme. With the flimsy collection typical of any newly established art museum, “moving in a more contemporary direction” is a complicated, time-consuming process.

The people at the Hubei Art Museum realize that there is more to art museums nowadays than collections and exhibitions. Public education is a necessary part of running any such institution. The challenge of interacting with today’s public, of nurturing their appreciation for art— especially in a city where “going to the art museum” is not part of anyone’s daily routine— has seen the staff here come up with some unique ideas, such as inviting artists to come paint on the premises to demystify the process of producing art, or sponsoring a debate competition for college students (topic: Chinese ink and wash painting’s relationship with modernity) that was the subject of much local media attention.

But even with all the hardware in place, software remains a challenge. Lang Xuebo, director of the Hubei Art Museum’s planning and outreach department, recalls participating in an international museum symposium: while Western museum directors discussed the conceptual and academic side of exhibition planning, the majority of Chinese museum directors were focused on how to raise funds and how to balance various interests. The difference cannot be blamed entirely on their forging unthinkingly ahead. Like most things in China, art museums are in a nascent stage. Many problems remain to be solved, one of which is the system itself. A relatively enlightened political leader is a boon and a blessing for everyone toiling underneath him. But any change in leadership could render all that toil for naught. Also like many things in China: a lack of mature mechanisms forces a reliance on a few key persons.

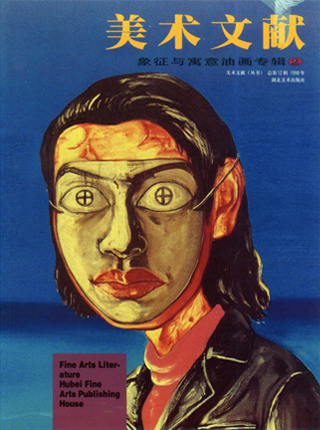

According to Liu Ming, head of the Wuhan gallery Fine Arts Literature Art Center, “the ’85 New Wave in Hubei actually came from inside the system. The leaders of the provincial artists association put together a big event, and all of the young artists— and even some of the more established artists— were there.” At its launch in 1993 with art critic Peng De at the helm, Fine Arts Literature magazine was also firmly situated inside the system. In the 1990s, art magazines played a very different role from that of today. Artists and critics were all active participants. Liu Ming says that, in those days, Fine Arts Literature ended up forging very close relationships with a number of artists, including a few Hubei natives like Zeng Fanzhi that would go onto later fame. When it came time to open the Fine Arts Literature Art Center, these relationships were the foundation off of which it was built.

The Fine Arts Literature Art Center was founded in 2003 as a share-issuing entity, but one whose actual status remains formidably complicated. Although the “center” ran a gallery and published a magazine, it maintained its “non-profit” status, and, along with it, an uncertain relationship with the government. From the outside looking in, it is not easy to understand how one entity could possess so many apparently conflicting identities. And yet such an arrangement is not uncommon in Wuhan. “Compound” institutions such as these arose as a response to holes in the city’s art ecosystem. Their existence illuminates the ecosystem’s response to the outside environment.

Liu Ming compares the story of the Fine Arts Literature Art Center to a fossil bed: with each layer one excavates, one finds more of the traces left behind by the changes in Wuhan’s contemporary art scene. Wuhan was an important battleground during the ’85 New Wave, producing a crop of influential artists and critics. It also saw the meteoric existence of The Trend of Art Thought magazine. Although its sponsoring institution was local, the magazine itself was a national publication. Issues with “too much experimentation” would lead to its shutdown, but during its brief life it provided a home for both Peng De and his deputy editor-in-chief Lu Hong. The magazine bore witness to many of Wuhan’s artists pulling up stakes and moving “up north” or “down south” during the 1990s.

In 2004, ten years after its first issue, Fine Arts Literature organized the “Inaugural Fine Arts Literature Nomination Exhibition.” Liu Ming recalls, “I thought the first exhibition was an important one. At the time, Wuhan had lost a lot of people. This exhibition might serve to bring them back together again.” In 2007, the organizers asked well-known curator and Wuhan native Pi Li to oversee the exhibition’s second installment, which would turn out to be the Hubei Art Museum’s grand opening exhibition.

Although the market for art in Wuhan never really took shape, the Chinese contemporary art market’s journey, from nonexistent to existent and then from being white-hot to cooling down, couldn’t help but be reflected in the rise and fall of galleries here that choose to operate inside the system. Nowadays Liu Ming will sometimes bemoan how conservative he was at the market’s peak. But, at the start of things, the status of his “gallery” was dubious, mired between for- and non-profit. The first time he attended a conference, he came away with his head spinning. Only gradually did he fumble his way towards an understanding of terms like “consignment” and “representation.” Despite his initial ignorance, later on he did manage to cart some works by young artists like Gong Jian and Li Jikai up to an art fair in Beijing, where they promptly sold out. Liu says that mature collectors in Wuhan are few, and galleries even fewer; however, people are gradually beginning to make their way in. The many discrete functions that the Fine Arts Literature Art Center has spent so many years performing will eventually be split up and taken on by others. Liu now spends his days thinking about the future direction of his institution.

THE THINGS THEY ARE A-CHANGING

ON TWO CONSECUTIVE days, in two separate spaces, the gallery K11 held two separate openings. The first— curated by Pi Li, Gong Jian, and Li Jianchun— went by the name “Something Will Inevitably Happen.” The second— also curated by Gong Jian, this time in conjunction with Wei Yuan— was titled “The Things They Are a-Changing.” The first ceremony had all the trappings of a typical second-tier city event, complete with speeches from dignitaries, ribbon cutting, fireworks, and ornamental hostesses— all things one would never see in Beijing or Shanghai— to mark the opening of the “Wuhan K11 Art Village.” The “village” has exhibition space, along with space for residency programs. The majority of the artists exhibited were from Wuhan, along with a few works from non-local artists like Chen Xiaoyun, Hu Xiangqian, and Yan Xing. “The Things They Are a-Changing” opened in K11’s space inside the Wuhan New World shopping center, and was, in its layout and atmosphere, more what one expects from your average art event. The three artists featured all hail from a younger generation and live and work in Wuhan. Attendees discussed and debated among themselves. Occasionally one heard someone pointing out some artist who was “the person to keep an eye on in Wuhan.” As conventional as the exhibition was, it succeeded in that it was demonstrably an exhibition.

K11’s backers are the Hong Kong real estate developers responsible for the “New World” series of developments found all over China. Such tie-ups between art and real estate are hardly a new phenomenon. The first signs of collaboration were apparent as early as the turn of the millennium, and as Chinese contemporary art has developed, cooperative relationships between the two worlds have flourished. In 2001, Ai Weiwei was invited to plan a series of public sculptures at Beijing’s first SOHO development. Shortly afterwards, “art centers” started popping up all over Beijing— mostly of the flash-in-the-pan variety. Staging an art exhibition was cheaper than a personal appearance by a celebrity, and seemed to be “more cultured and more tasteful.” Even if the money in art was just a fraction of that in real estate or entertainment, in the public mind at least, “contemporary art” gradually gained enough cachet to partially displace the glittering world of celebrity. Despite some hiccups in their initial forays at cooperation, the relationship between art and real estate did not break down; rather, it helped generate a new model. Using nearby Hunan as an example, the third annual “Art Changsha” exhibition lacked the air of ironic mockery it had in years prior. No longer qualified to make snide remarks like they once could, the participating artists, curators, and critics were reduced to mocking themselves. Money is now the most important driving force behind trends. That being said, the ability to coordinate a group of professionals and sustain investment over the long haul is still what separates the true, long-lived galleries from the amateurs. It remains to be seen whether K11 can affect this kind of change upon Wuhan’s art scene.

The day after its opening, Pi Li hosted a forum as a follow-up to “Something Will Inevitably Happen.” The majority of the speakers were not from Wuhan— Bao Dong and Colin Chinnery come from Beijing, Nikita Yingqian Cai from Guangzhou, and Robin Peckham from Hong Kong, to name a few. Clearly these “imports” were of no small import, even if, after the forum finished up, some of the befuddled local attendees professed that its discussions on “artistic intervention in society” left them with a headache.

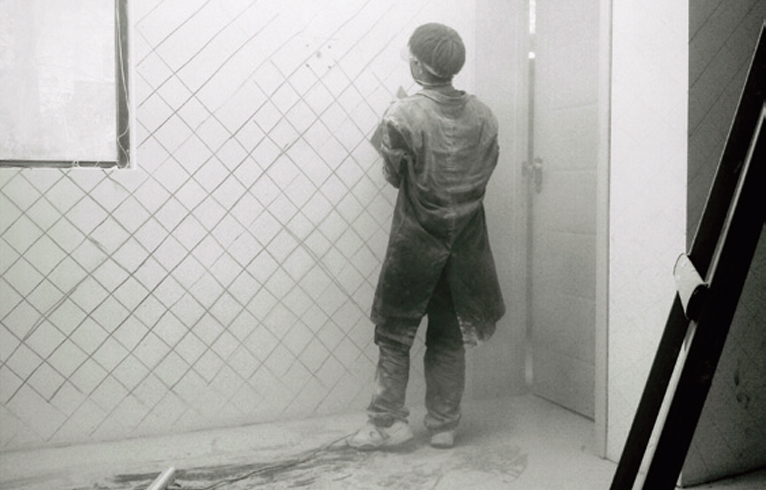

If K11, with its exhibitions and forums, seems like the improvised outburst of an infusion of “foreign aid,” the Yangtze River Space is just the opposite: a dark, quiet current flowing underneath Wuhan’s urban skin. The brainchild of the artists Gong Jian, Cai Kai, and Li Jikai, Yangtze River Space opened its doors in 2011 in Li’s small three-story house far outside the city center. The organizers’ summary of the character and aims of their project is succinct: “The costs for the space are all paid with donations from sponsors or small groups. We don’t host commercial events. Our aim is to provide like-minded individuals with the chance to make their plans a reality, and to work hard to give this city a space for communication and exchange.” The project’s methods and agenda are much closer to the “Chinese contemporary art” we know so well. The roster of artists that have exhibited to date includes Hu Xiangqian, Jin Shan, Chen Wei, Yan Xing, and Li Jinghu, while talks by Pi Li and Wang Min’an have been amply attended. Gong Jian recalls that “All the art youth at Yan Xing’s show were completely bowled over. Three of them cried after they saw his video.” Here, Gong might be exaggerating slightly, but there can be no doubt that the Yangzte River Space has given Wuhan a window through which to communicate with the outside world. Artists brought in from outside Wuhan have given the local creative scene a jolt. To say it is “pointing the way forward” might be overstating things; “broadening horizons” is more accurate. Only if one knows what is happening out in the wider world can things begin a-changing closer to home.

Tracing the relationships between the various members of the art world is always a fascinating exercise. Despite the difficulty of mapping them out precisely, they are not without their use. Fu Zhongwang made a speech at the K11 opening; Liu Ming also dropped by. Gong Jian has staged solo shows at the Fine Arts Literature Center. Lang Xuebo participated in “Something Will Inevitably Happen,” and is a fixture at Yangtze River Space events. Each and every one of these artists has their own close-knit relationship with the Hubei Institute of Fine Arts: student-teacher relationships, cooperative relationships, and friendships. Hubei’s art world is not large, and the artists in it are known for being “independent,” “wild,” for “going their own way.” This is, of course, a sign of openness and strength. But in a city like Wuhan— neither an economic center, nor a political center— each and every one of the people who choose to stay behind are, by default, anointed builders, charged with the task of ensuring that those “inevitable changes” do, in fact, a-happen.