LOSING FRANK

| 2012年03月09日 | 发表于 LEAP 13

In Chinese medicine they say that those who won’t make it through the following year tend to leave for good in the winter. It’s a theory that may sound folksy but that this winter was borne out by a string of monumental passings that seemed never to end. And no sooner had Christopher Hitchens, Václav Havel, and Kim Jong-il departed than cancer had claimed one of the Chinese art world’s own deepest thinkers and dearest leaders: Frank Uytterhaegen.

Born in rural Flanders and educated in Ghent, Uytterhaegen found his way to China in the mid-1980s after years as a university researcher. A product of that keenly idealistic decade in Beijing, he set up, with great success, the China branch of IBA, a high-tech firm that mainly produces cancer-treatment equipment.

On January 3, the mourners parked their cars in a line down the street that used to lead to the only gallery in Caochangdi. The China Art Archives and Warehouse, founded by Uytterhaegen, Hans van Dijk, and Ai Weiwei in 1998, is housed in one of two buildings on a serene courtyard; the other holds his family’s residence and the Modern Chinese Art Foundation, which he and his wife Pascale established in 2000. The CAAW may not have been quite as active in the past five years as it was in its first five —a period when it discovered the painter Li Songsong, or showed the monumental “Three Gorges” cycle of Liu Xiaodong— but a show did fill its stark rectangular volume: a floorful of Mao Tongqiang’s granite panels carved with the words to Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech in Xixia pictographs.

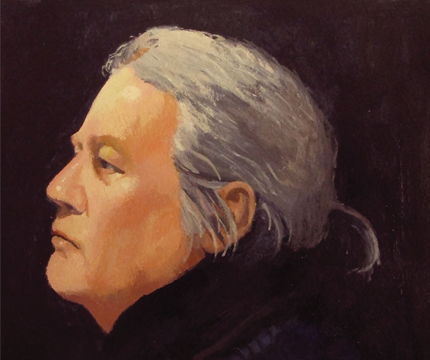

“It’s Frank’s friend, from the provinces,” explained a bespectacled Chinese fifty-something in perfect English, likely a colleague of Frank from one or another business venture. “He insisted on doing this,” said the man, pointing to the mourner, prostrate atop the carved stone tablets, swaddled in white gauze with a long cloth train upon which visitors were to write their farewells. White blooms adorned the poured concrete staircase, and dim light bathed the gray brick walls. We stood and watched the funereal PowerPoint, a photographic litany of a life well lived in China: the young couple embracing in a wheat field, the growing children Carl-Willem and Aiko in front of one or another temple, the mature Frank giving the camera ironic who-me gazes while holding a glass of red, offering advice to some now-famous painter, or standing belly-to-belly with his old friend Ai. The mourners lingered and lingered as the slideshow looped, then dispersed into the freezing air.

Quite beyond the family and friends who will grieve Mr. Uytterhaegen acutely, there is a much larger orbit of those who knew him casually, as the champion of a newly vibrant scene before a still dismissive audience in his native Europe. We are happy to have seen him do this, if only from a distance.