FROM DESTRUCTION TO CO-CONSTRUCTION: THREE CASE STUDIES OF ARTISTIC PRACTICE AND THE MUSEUM

| March 16, 2013 | Post In LEAP 18

Here, we cull from art history three examples of artist interaction with the museum. In the mid to late 1980s, three works by Huang Yong ping and Xiamen Dada adopted a destructive attitude to directly challenge the establishment, burning artworks and even planning to “tow” away a museum. after the turn of the century, artist actions taken to directly challenge the museum system have grown increasingly rare. growth in the commercial appetite for art and a healthy rise in the number of new museum projects combined to give artists more opportunities to work with museums instead of against, an example given here being Zheng Guogu’s robust line of inquiry into the museum from the early 2000s. Meanwhile, young artists in the 2010s are issuing tougher but more refined challenges to the art establishment than their predecessors.

HUANG YONG PING AND XIAMEN DADA

The Burning of Art/ The Fujian Art Museum Incident/Drawing Away the National Art Gallery

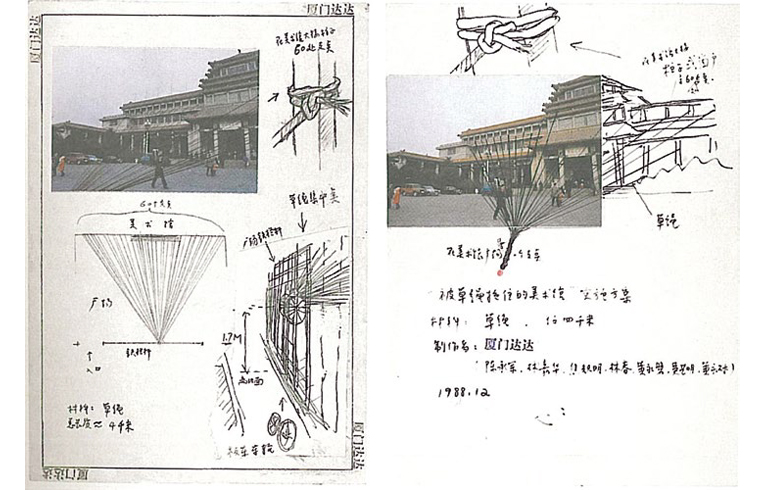

The ’85 New Wave movement saw the rise of a new group of young Chinese artists, among whom the Xiamen Dada collective were considered the most radical. Huang Yongping was the leader of the group, having organized and led it from 1983 to 1989. Also included among the 13 total members were Jiao Yaoming, Lin Jiahua, and Yu Xiaogang. together Xiamen Dada undertook a series of performances aimed against the museum system, leading to much debate and introspection in the artistic community. the first was a burning of their own artworks in front of the Cultural palace of Xiamen on November 23, 1986. The collective followed that up with an exhibition in Fujian art Museum in December of 1986, when they showcased construction material from nearby building sites alongside an announcement that the exhibition hall was available to rent. the exhibition was shut down within two hours. In 1988, Xiamen Dada devised the plan “Drawing away the national art gallery,” which was never realized except on paper.

With the “events” exhibition at the Fujian provincial art Museum exhibition, Xiamen Dada attempted to relieve the museum of its long accepted function as a display space for artwork. they proposed a plan of “dissolution,” aiming to dissolve the elevated status of art, artworks, artists, and the system of official registration held by the establishment. Huang Yongping felt that under the existing governance of art, the determination of whether an artwork may be considered a work of art was completely meaningless. he writes about his performativity in Fighting Art in the Name of Art: “to exhibit objects that are clearly not works of art in the museum is clearly paradoxical. the existence of this paradox is due to people’s reluctance to let go of their predetermination of what art should be. the only way to dispel this paradox is for the art museum to transcend its conventional function towards infinite adaptability.”

Xiamen Dada sought to progress towards transcending or destroying the picture plane. Huang Yongping explains the intention of burning their artwork in 1986: “This is a ceremony, a ruthless non-artistic treatment of artworks. Only when the work is burnt by its creator do we see the true meaning.” When they moved construction materials into a museum that December, the aim was not to challenge the viewers or the museum, but rather the artistic authority in China at the time. in the 1987 article “Art—An Inauspicious Thing,” Huang not only confronts the mechanisms of art and exhibition, but also questions the very goals that we aspire to, and challenges the development of art in general. his main goal was to create a “society that refuses art.”

ZHENG

ZHENG GUOGU

Reconstruction of the He Xiangning Museum

In 2003, Zheng Guogu created a scaled-down version of the He Xiangning Museum for “Fifth System: Public Art in the Age of Post-planning—Fifth Annual Shenzhen International Sculpture Exhibition.” Zheng is especially interested in “illegal constructions.” To him, the interior functions of the He Xiangning Museum had been lost, so he abstracted the building into a sculpture. The reconstructed he Xiangning Museum is situated over roughly 1,200 square meters (60 x 20 x 9 m) on a square in Overseas Chinese town. A 10 x 10 m space dutifully copies the original building’s architecture, while the rest is realized through scaffolding. This “illegally constructed museum” remained in place as a sculpture for two years, during which many local residents complained that it interfered with their daily lives and spray-painted the “demolish” symbol on it multiple times. At the same time, the interior of this reconstructed museum was used to exhibit art by children from the nearby community.

My Home Is Your Museum

In 2002, Zheng Guogu bought seven apartments in his hometown of Yangjiang (at RMB 1,280 per square meter). The apartments were on the seventh to ninth floors, which he opened up and convinced the builder to construct according to his own designs. the newly constructed space not only serves a function as a home, but also has plentiful working space. On the ninth floor roof, he even put in a giant water tank. Looking up from the seventh floor, the space looks like an aquarium. Zheng refers to it as the “illegal construction within the illegal construction,” as the building project itself never received official approval. In 2004, Hu Fang coined the term “My Home is Your Museum” for Zheng’s seven-apartment construction. The “scenery” he created in this space was refined and exhibited in Vitamin Creative space. The project studies the interchangeability between art and life. To understand the theme “My home is Your Museum,” we must look into Zheng’s past experiences. He had worked as an interior designer in Yangjiang for many years. His goal to “decorate a home as though decorating a museum” is not just his creative drive; it is also the very concept that he preached to his clients over his working career. For Zheng Guogu, “art does not exist outside the context of life, nor does it exist within— art and life are one and the same.”

Birds Flying Into Rain Pattering On The Plantain Woods

In 2006, for “Infiltration—Idylls and Visions: Second Space for Contemporary Ink Work,” Zheng Guogu planted a small plantain forest in the Guangdong Museum of Art and provided the first half of an antithetical couplet: “Birds Flying into Rain Pattering on the Plantain Woods” and set out a large sheet of blank paper for viewers to come up with the matching line. More than 500 trees were transported to Guangzhou from Yangjiang in four trucks. Zheng hoped to reproduce a literati garden inside the museum, filling the space with landscaping elements such as plantain trees, small paths, stone bridges, scholar’s rocks, ink paintings, calligraphy, and “ponds.” The ponds were filled with crumpled calligraphy scrolls resting on top of mechanical massagers; when turned on, the effect was not unlike the waves of a natural water pond. The planting of 500 trees indoors posed a challenge to then-director Wang Huangsheng, who not only had to consider how an audience would perceive the work, but also deal with the odors and bacteria of plant decay during the duration of the exhibition. In the end, the show was successful, and thereafter the trees were transplanted to the museum’s courtyard, changing the landscape of the museum in a meaningful way.

HU XIANGQIAN

Xiangqian Museum

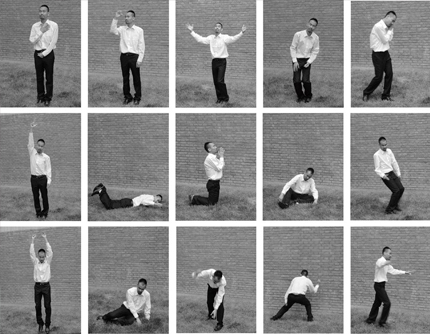

In 2010, Hu Xiangqian performed the piece Xiangqian Museum at Taikang Space in Beijing for the first time, using his own body as a medium for the exhibition of 16 artworks. There are five versions of Xiangqian Museum, which he subsequently performed in Manchester, England, as well as at the Times Museum in Guangdong. The name of the piece alludes directly to the physical space in a museum. The artist attempts to replicate the museum’s traditional functions of collection and exhibition using his own body. The artworks he acts out include those that have left a deep impression on him, as well as his own past creations: “Everyone is born to be empty. We need materials and non-materials to fill ourselves. A museum fills itself with materials, but through my eyes and my mind, a typical museum would turn into non-materials. and in my performance, these museums and artworks are represented through my body to the audience. I think the best thing about art is we can carry it wherever we go.” In describing his works, Hu focuses primarily on converting material possession into mental possession. For him, the educational purpose of museums is hypocritical; so-called education should be a proactive process for the audience, rather than a passive acceptance of the museum’s choices. Hu Xiangqian does not oppose the museum as a “white box,” equipped with modern technology and conveniences. like many other young Chinese artists, he actively seeks to collaborate with museums, art institutions, and independent curators. In the ways he questions the museum establishment, Hu Xiangqian is much more resilient and skillful than his predecessors from the 1990s.