ZHAN WANG: FORM OF THE FORMLESS

| 2013年05月10日 | 发表于 LEAP 18

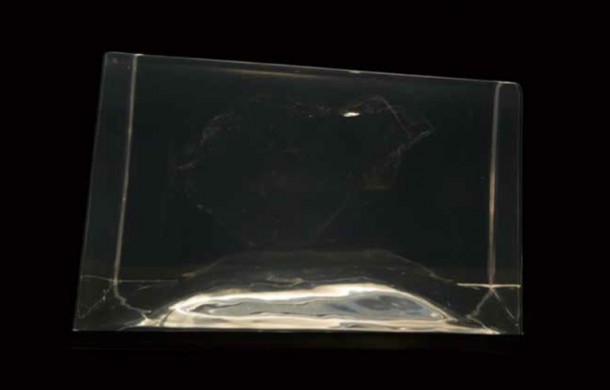

These new works by Zhan Wang continue his explorations of the nature of the universe and the forms that make up our understanding of it. Long March’s galleries have been divided into two areas, which might be characterized as a light space and a dark space. The light space presents floor- and wall-mounted panels of smashed rocks painstakingly recreated in the artist’s signature stainless steel, along with a centerpiece block of resin holding the ghosted shape of another rock suspended within. On the ceiling, a spotlight punches through a small opening so that, on the other (dark) side, a cone of light crosses the room, catching motes of dust in its beam. Aside from this penetration, the dark space simply presents two small video monitors, stacked on top of each other behind a column. One shows a rock suspended in deep blue ocean waters, and the other the documentation of how this first video was produced (by attaching a camera rig to the rock and dropping both into the sea).

Zhan Wang’s “My Personal Universe,” the large installation that he produced in 2011 for UCCA in Beijing, seemed like hubris in its grandiose intentions: from scale to interpretation, it aimed higher than it was able to reach. This new set of more modest works makes it clearer that, despite these grand schemes, the artist is in a continual process of experimentation that strives for perfection, but continually comes up against the imperfect nature of matter. This imperfection in the execution (the steel is never quite smooth) and final display of the objects (dust on the mirrored surfaces) perhaps, inadvertently, say much about the nature of the reality that Zhan is presenting.

Zhan Wang seems genuinely committed to his chosen forms. The technical skills developed in his pursuit of the perfect finish for his famed stainless steel Taihu rocks has fed through to the creation of these new high-finish stainless steel panels. The polished rocks are also juxtaposed with a sand-like surface— reportedly made from ground rock mixed with paper pulp. The nod towards the flat surface as a presentation device promotes its nature as a plinth, holding this in play with its nature as the material from which the rock particles are formed. This could make for an interesting commentary between Zhan’s “macro” reading of the rocks as connected to the universe, and their “micro” or local sense, as art objects— although this is not explicit.

Moving away from the forms that make up so much of Zhan Wang’s most visible works, the beam of light and the video are the more interesting experiments in this show. That said, the video of the rock being dropped into the ocean threatens to be neither one thing nor the other. While fitting into Zhan’s penchant for large-scale projects to place his rocks in relation to the world (taking a stone to the top of Everest, an unrealized project to return a stone to space, and so on), this new piece’s installation seems restrained in its small and discrete presentation. The effort involved in developing this project, including the creation of the elaborate camera rig, is in marked contrast to a simple event— a rock sinking. The resulting video seems almost comical in its depiction of this event—the effort far outweighing the results.

Zhan Wang’s works seem to want to have their cake and eat it too: they seek to play with the forms and their relation to the formless (hence the exhibition title), yet at the same time, to play on the margins of a highly visible monumentality. This ambiguity is actually what makes this show more successful than “My Personal Universe.” Maybe these works should be classed as “heroic failures,” as records of grand attempts that never quite reach their planned effect, and stand in powerful relation to the vicissitudes of reality.