THE HARM OF DEFINITION : A CONVERSATION BETWEEN SU WEI AND LIU DING

| 2013年08月08日 | 发表于 LEAP 21

SU WEI When we work together, many ideas, anxieties, and problems are interrelated and sometimes projected onto each other. Though these connections are not always apparent, our collaboration has been based upon a common ground we share when we discuss, initiate, and explore things together. Looking back on our past collaboration, I would say what we share is a stubbornness for art-making.

For the exhibition “Little Movements,” we proposed that all people in the art system are equal practitioners exercising various forms of creation. What is the act of creation? What is the foundation to all these occupations—artists, critics, curators, gallerists, collectors, publishers, and educators? Why are they (we) equal? I have heard doubts from people working in other industries; they suspected that our proposed equality is the reverse side of the same coin that reaffirms the power structure in the art system. But for many practitioners, this equality is self-evident, and they feel there is no need to discuss the matter.

LIU DING I hope our discussion does not stray too far away from the topic of art-making, in which you and I share certain common ground. The way I see it, the allure of art-making lies in the distance and apparent disconnection between art and non-art systems I refer to in my work. This gap gives me the most anxiety and excitement, producing moments of desperation and feelings of powerlessness. Particularly in these moments, I reconsider the ideas of equality and art making as inspiration for deeper understanding and imagination of my role as an artist.

With “Little Movements” and the Shenzhen Sculpture Biennale, we began with these inspirations. We proposed that every kind of work has aesthetic value and this value cannot be condensed into mere descriptions or definitions. If we seek to achieve descriptions or definitions, art making will fall into utilitarian logic. In the past we have produced too much work that strived towards definition. The ideas of equality and returning to art making are urgent issues for me. In my practice these are not utopian ideas, but a way of returning to being human, including doubts, indecision, uncertainties, inabilities to describe, and failures. I think as a creator I must confront, respect and understand these things as they are, and not for the sake of perfection.

SW Our thoughts about equality and art-making are clear and focused, and inspired by our dissatisfaction with pre-existing historical narratives that reduce vibrant artist careers into goal-oriented tales. Many critics and curators, in particular, take learning history as a kind of technical training. Its writing, then, can easily be bred into specialized skill (which is a good thing; this skill most often appears in the hands of faux elitists, via the so-called theoretical interpretation of artworks).

But back to the question of art-making: on the most direct level, this involves the critic and the curator. If we see art as a way to confront, question and explore the world, to return to art-making means to return to the time before our questions were defined. The trouble of posing questions—forget about questioning our questioning—is that when we make art we constantly think about how we formulate these questions. The same themes lay behind the discussions of “what is experimental art” and “what is conceptual art” in the 1990s. Today, it has clearly emerged in the present dilemma of artistic practice.

Returning to creation, then, is not a task only for curators and critics; all practitioners must face up to this call. Here, is it necessary to define the parameters of this return? In other words, it is not only a call for change in the working method (as if our return to creating means to return to concept from expression, or to return to expression from concept). Returning to creating is not an issue of our value system, and definitely not a question of body politics, of making the artist monastic. From my understanding, art making is about coexistence. What do you think is the essence of the relationship between coexistence and creation?

LD Coexistence is the basis of a lot of research and artistic practice today. Like the research we did about Chinese art of the 1990s. Art made at that time to me feels both distant and close. I cannot clearly express how these works have influenced me, but the influence is great. In the process of our research, which began with limited scope, I had the distinct feeling that what we heard and saw of these works before was inconsistent with what we actually came across. If our research is made in the name of foregone conclusions, then we must seek corresponding materials to vindicate these. But what does this mean for art-making and research itself? History provides us with a distance of time. It gives things and relationships a space to grow on their own. History needs to be reviewed time and time again, instead of becoming fact after its first definition. As the art world celebrates definitions of the past and future, definitions are also harming all its participants. They only serve to convert artists into servants. To refuse definition means to refuse to become a servant and return to the role of a creator. This is not just about taking a stance; it is a matter of urgency. Artists should see each other as equal creators who experience the good and the bad of life together—this dawned on me in my research of the 1990s. This kind of vision gave me new understanding of myself.

SW From my understanding, coexistence is a concept particular to post-collectivist society. In history we have experienced the consequences of advancing and retreating from this goal. Globalization has not only brought us a high stream of exchanges in various forms, it has also created complicated feelings that we are reluctant to express. Perhaps the problem is that people eagerly want to come up with (or reintroduce) a method that can bring immediate improvements. But such methods will only make things worse, because the difficult exploration and meditations in between various methods will be subordinated or simplified and transformed into passing stages of one whole process.

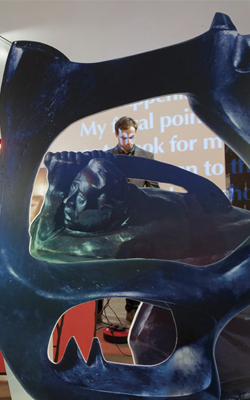

PHOTO: Lucy Dawkins for Tate Photography. Copyright Liu Ding & Tate

We have looked at many examples outside of China. We looked at how socialist conditions in 1960-70s Europe inspired the Situationists and the Fluxists to create art movements that called for personal expression and critical review of capitalist values. We also looked at Latin American art that struggled under Fascist government. Another example is the trend of social art practices in Europe and America in the 1990s. In these various forms of co-existence, art has contained political demands. If we are compelled to follow these forms of practice in our own social context, is it because we are anxious about art making? Are we insecure and distrusting of art? Or are we disappointed by our inability to form an art consciousness beyond the logic of our own value systems?

LD I believe coexistence derives from political evolution. Coexistence is a container for relevance. Coexistence offers conditions for committing crimes, but it also provides clues for inspection. I want to share with you a recent experience I had in my travels. It was a pleasant and real experience of coexistence.

In Italy a friend recommended that I visit a personal collection. I did not have a lot of time, and the collector was not home, but he permitted me to visit regardless. The next day, a middle-aged Italian man picked me up for the collection tour. I didn’t understand Italian, so we remained silent for the entire ride. The car drove past rivers and creeks, vineyards, castles, ski lifts… Finally we steered into a small valley, where a circular concrete building appeared in front of us. Half of the building was imbedded in the mountains, half of it sat next to the creek. As we stepped out of the car, a guard opened the four-meter high copper door and greeted us. We walked towards a four-story art museum, in which artificial and natural light fell softly on the gallery’s pale wooden floors. There was the sound of rotating film wheels and other mechanical devices… this was an art museum not open to the public. The exhibition had no name, no exhibition labels, no audio guides, no introduction, no artist names, no artwork dates, no other explanations whatsoever. There were only artworks hanging on the walls, placed on the floor, in black rooms, hanging in midair. There was art and that was all there was. I wanted to ask the guard some questions but we were unable to communicate because we did not understand each other’s languages. Our conversation consisted of occasional exchanges of artist names. This was a very interesting exhibition. Without any aid of introduction, the will of the works, of the narrators, of the proprietors were so present.

When an artwork as an ordinary object comes in contact with the universal values of the art world, oftentimes these values determine how we position and understand art. We use words such as criticize, reflect, and refuse very literally to discuss art. We never use real actions to deeper reflect upon our work. Ironically, I saw such potential in the private collector’s exhibition, where no explanation was provided.

SW Since our dialogue in 2008 in “Liu Ding’s Store,” your work has become more and more complicated, with many trains of thought happening at the same time. We have just spoken of some experiences that lead us to consider “the question.” Sometimes this is directly present in your work; sometimes it is absent. Most importantly, you believe in subjectivity, you insist on starting with “I” to confront the political questions in art. This state of mind had particularly interesting transformations in 2012. In July that year, you showed I Simply Appear in the Company of… in which you invited Tate curator Marko Daniel and independent curator Carol Yinghua Lu to engage in a discussion of your work. In this group conversation you played the role of “Mr. Liu,” which appears to be a humble generalization of Liu Ding. I think within this roleplay is also some theoretical advancement of your understanding of socio-politics. I wish to hear more about this. Recently, your two works Un-erasable and I Simply Appear in the Company of… plus your forthcoming performance at Tate called Almost Avant-Garde have all involved the idea of weak performance. I wish to hear more about your process of reflecting on art-making through making art. To reexamine art audiences and boundaries through art— is this your understanding of what it means to return to art-making?

LD In my practice there are many developing threads and states of expressions, I think it will be like this in the future as well. The inconsistency this state encourages me and molds me at the same time. In I Simply Appear in the Company of… I directly used the gap between inconsistencies to create a work of art. Within this gap there is a resemblance to criticism, which I hoped to emphasize by using the first person. A lag begins to form between the expression of the individual and the progress of time. To be in the plural while conversing with people that understood me felt the most natural to me.

My last series of “performance” works were primarily inspired by my dialogue series. After seeing these, many people ask if I have started to make performance art. At first I was a bit confused by this question. Obviously what I do is not technically performance art. I loosely offer them the term “weak performance,”which I define as “a performance or action within the framework of premeditated performance or action.”

In such recent works, I take my own and other artists’ works as material, and present them together through photography or screening. This creation of (dis)connection directly addresses the connection between me and others, as well as the generally incommunicable.

I think art-making in and of itself is suitable material, a realistic and critical method, for testing its own audience and boundaries. To advance as both material and method is like multiplying a cell, in which the process appears to be nothing out of the ordinary—but as artists, to observe such subtle transformation is our greatest challenge.