WHAT WE TALK ABOUT WHEN WE TALK ABOUT HUMOR

| November 14, 2014 | Post In LEAP 28

NIETZSCHE’S RALLYING CRY presages postmodernism. Many believe that, with the advent of postmodernism, we are finally freed from the weight of history to pursue a more relaxed, freer, pluralistic life of pleasure. Everything will flow, and burdensome realities will dissipate as laughter rings out. Not so long ago, when Stephen Chow’s A Chinese Odyssey became the sound of its generation and gave voice to the thoughts of youth, some cultural commentators cried out that, because deconstruction and parody had entered mainstream culture, our value system was under attack from all sides. But looking back now, art that deconstructed or was deconstructed did not then exist: any comedy with a subversive or revolutionary stance had to seek a worthier measure. What should contemporary jokes be looking for? What do we mean by humor? To answer these questions, we must first recall how and why we laugh. Looking at the history of humor as an idea can help us see clearly the essential problems encountered by comedy today.

MODERATION AND DISCOVERY

HUMOR IS A common word, but for its precise definition we must look back at historical context. In ancient Greece, humor referred to the physical state of four types of fluid in balance in the body. This state of bodily harmony was closely related to a balanced spiritual temperament. Today, the word humor still carries these classical connotations of temperament—when we say someone is humorous, we are praising them for having a positive trait that implies a desire for harmony and moderation. On excessively serious, reserved occasions, humor is compared to a social lubricant; when we suffer the vicissitudes and unfairness of fate, humor becomes a byword for an optimistic outlook.In ancient times, the positive trait of wit or humor did not purely refer to joking, but rather was about being restrained when both joking and not. This is illustrated in a passage from Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics: Those who joke excessively become abusive and vulgar… Some jokes should not be made, such as those that mock or ridicule. Some things the law forbids us to mock or ridicule. We should even be forbidden from making these kinds of jokes. Rather than explaining what a joke is, Aristotle here explains why we must take care when making jokes. He believes that, if a person is to really pursue good, she must be- have reasonably guided by practical knowledge, must practice “restraint,” “moderation,” and the way of “the mean,” and must make sure never to be excessive. Otherwise, she will encounter evil and suffering (1104b33). In his Poetics, Aristotle defines comedy as an activity that mimics the funny nature of the buffoon, making people laugh and prevent- ing them from feeling pain (1449a32-36). That is to say, at least for the audience, comedy must display moderation to avoid feeling or heading towards evil and suffering.

There is another level of meaning to humor. Modern theorists believe that humor is related to the power to effect change on and rearrange the logic of everyday life, as Schopenhauer claims: “Laughter occurs with every sudden realization that object and idea are not aligned.” Leaving the classical world behind, the human trait of moderation is no longer as important under modernism, and humor begins to be defined by the discovery of new reasons and ideas. A joke or comic performance, appearing for the first time, has to imply the breakdown of convention in the real world; the deeper-seated the convention to be broken down, the funnier the humor. In The Frogs, for example, Aristophanes has Dionysus, the mysterious god of wine, enter by riding on a donkey, which comes as a surprise to the audience and gives them the fresh idea that a god can arrive onstage in an ordinary, human way.

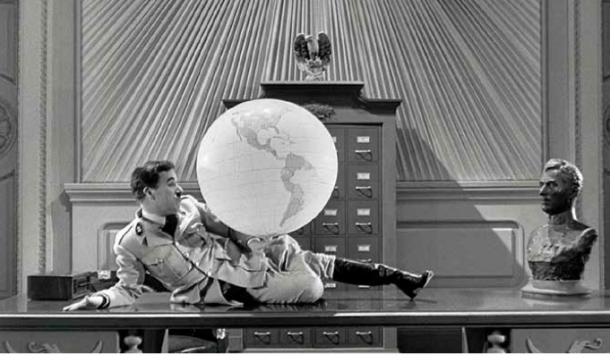

Modern artists and writers use yet more obvious and distinct techniques to articulate things that are already prevalent in their lives but have not yet been put into words. Presenting them in a comic style helps viewers and readers learn new ideas, ways of evaluating things, and feelings. In a scene set in an office in Charlie Chaplin’s film The Great Dictator, for example, Hitler juggles a globe like a circus clown, showing the audience that even a despot can actually have a comic or silly side. This scene gives the audience a new way of thinking about a tyrant, freeing them from the fear and anxiety that comes from being weaker and thus giving them psychological confidence. In this way, The Great Dictator effectively tempers with subversion the apprehension felt by the wartime audience; it is a successful comedy in the tradition of the Aristotelian principle, but with a generational flavor. By comparison, no one finds the old comedic sketches drawn from internet culture for Chinese New Year television programs funny, because they are old chestnuts well-known to the audience with no element of discovery at all.

Today we find new discoveries everywhere, so our lives have become ever more entertaining—but does that necessarily mean that our intelligence and ability to reason are also gradually improving? In fact, many thinkers believe the modern theory of humor that emphasizes discovery is the sign of a strongly rational spirit. Alexander Pope believed that wit was “correctness of thought and ingenuity of expression” and the “artistic expression of reason.” Humor is a natural outlet when reason reaches a certain level; in its highest state it can even reach spiritual transcendence. This is similar to the spirit of the carnival in Western traditions. In ancient Greece, by mocking the Dionysus of The Frogs, people could experience a Dionysian spirit that gave them temporary release from the strictures of convention and taboo, and allowing them to unite with the gods. Here, humor becomes a conduit to the divine. This kind of divinity was, of course, different from the sense of stability and security offered by normal religion—to use Nietzsche’s term, the Apollonian—in that it stresses the superiority of the intellect in dealing with human suffering. Thomas Hobbes once observed that laughter is a kind of “sudden glory” produced by comparing our own past weakness with others and suddenly realizing our present sense of superiority. Similarly, the scholar James Sully writes that: “[Humor’s] most apparent, if not most important condition, is a development of intelligence… The distinguishing intellectual element in humorous contemplation is a larger development of that power of grasping things together, and in their relations, which is at the root of all the higher perceptions of the laughable.” According to this explanation, no one who has mastered humor or the art of laughter is intellectually weak; at the very least, she has seen clearly, through jokes, the world’s innate contradictions and absurdities and has thought of a rational explanation, then incorporated the things in ourselves or others that are laughable to make the leap to a higher level.

CONTEMPORARY MISREADINGS OF COMEDY

IF COMEDY IS to achieve tempered realization, the precondition is sufficient self- awareness, including a recognition of one’s own role in society. Arrogance (holding one- self in too high esteem) and low self-esteem (feeling oneself is not good enough) result not in comedy but in an antisocial destructive force. Sully points out that an incorrect way of poking fun, such as an arrogant attitude, can damage friendships between people, whereas true comedy benefits social relations and can aid community integrity. With the advent of modernity, we have gradually lost the ability to be shocked at cruel humor. Perhaps the quantity of laughter can be used as an indicator of the standard of comedy? Laughter can also be a superficial, self-masking tool. This allows a deeper question to surface: is the sense of superiority to which comedy gives expression true self-confidence and strength, or is it just a pose for others to see?

Some comedians try to be deliberately self-deprecating or self-mocking, which ironically shows narcissism, a sense of superiority, and arrogance, and has already become a common fault of our times. One example is the mass internet craze of calling oneself a diaosi, or loser. Around 2010, with the increasing wealth gap and social inequality, many young people started to realize they would find it hard to break down existing barriers and attain personal success. This harsh reality leads them to give up and stop trying, ridicule themselves, and oppose anything of real value. In terms of psychological motivation, this is a kind of concealed dissatisfaction with revolution. One should always have an awareness of escaping her lowly position, not remain resigned to a desperate and wretched fate. Many of these internet “losers” are really expressing a bold and free spirit, rejecting the inequities of contemporary society. Given that this is the utmost expression of their self-esteem, this kind of cynical humor is clearly a kind of irrational, excessive jok- ing beyond the control of reason.

From this we understand that the liberalization of modern comedy is basically a process of separating intellect and restraint, along with the addition of arrogance. The spirit of the times, in which unrestrained play and laughter express individuality, encourages the mistaken idea that demonstrating a sense of superiority equates with true intellectual superiority. The proliferation of internet spoofs and parodies is precisely this kind of fake intellectualism.

A good and truly humorous comedy must naturally be filled with discoveries of all kinds, and discovery is clearly related to intellectual activity. Intellectual discovery has a basic characteristic, which is that only the person who first encounters it can enjoy the pleasure of discovery. If an artist who takes responsibility for being funny lacks a self-awareness of the intellectual dimension or curiosity about new questions and new subjects for comedy, then she is simply plagiarizing the progressiveness and depth of others, no matter how progressive or deep her thinking might be.

An extreme example is the entertainment industry, which deliberately creates laughing points in popular culture and pushes the boundaries of taste. There are now commercial organizations that use media psychology to analyze viewers’ reception of sketches, xiangsheng (dialogic comedy double acts), talk shows, comics, variety shows and so on, trying to find out which jokes or sketches can attract more online views in order to seek out or commission the same kinds of pieces. Of course, the commercialization of comedy is nothing new; there were professional playwrights who specialized in comedy even in classical times. But the problem is, the modern laughter industry has turned its bacalready familiar laughing points, hitting a series of new lows. Once the habitual joy has passed, they have no way to reach a higher level or surpass themselves.

Zhao Benshan’s sketches and television shows are a very good example. In the 1980s and 90s, he attracted viewers by making the rural population the object of his ridicule, as they had not yet been brought into the process of enlightened modernity. But today, when the basic economic and social structures of the countryside have been broken down and the lines between urban and rural populations are ambiguous, this kind of deliberate distortion has lost its naturally appreciative audience. Degenerating into vulgarity, it encounters resistance. By the same token, when Jiang Kun takes sketches that have been broadcast on the internet long before and puts them on stage, what we see is not intelligence, but rather the most desperate stupidity.

Four-panel comic strips are another example: the stylized rhythm of this short genre leads it to follow a conventional narrative structure, stultifying the comic effect to the degree that, in most cartoonists’ work, one finds identical themes and characters. Similarly, when the Japanese Gag Manga Biyori series of nonsense spoofs became popular, Chinese cartoon producers, like the producers of One Hundred Thousand Bad Jokes, did not consider gaining inspiration from rich traditional materials and contemporary life or establishing their own system of expressing humor. Instead, they copied their predecessors in everything from drawing style and musical score to subject matter, and gathered popular jokes from anywhere and everywhere to pad it out.

But we also see that, by preserving some traditional art forms, a certain standard is maintained. The xiangsheng or comic double acts of Guo Degang and Yu Qian or Miao Fu and Wang Sheng use observation and understanding of the real world to extract original comedy (sketches like “The Five-Star General Corporal James” and “The Water Margin Butterfly Lovers,” for example, briefly burst onto the scene and stimulate lively thinking). Beyond having individual style and displaying a sense of superiority, sketches like these can also give and take. Of course, this is the very nature of xiangsheng as an art form: in its traditional comic structure, a “straight man,” who represents the logic of normal behavior, repeatedly contradicts and criticizes the “funny man,” who represents the logic of discovering the bizarre or fantastic, revealing the clash of two world views and highlighting a sense of newness while guaranteeing that the topic has a certain level of restraint. The best xiangsheng artists of our time do nothing more than bring out and develop this basic property. Some works that have comic elements similar to those of xiangsheng have been worth seeing, including many films of Stephen Chow and Ng Man Tat and even the recent film Lost in Thailand. Stupid and unhappy are not just the respective moods of two characters—they also hint at the organic synthesis of two basic comic ideas: restraint and discovery.

In a commercialized world, this system of traditional arts can encounter unfair opposition. In a postmodern context that values systemic deconstruction, the role of the funny man has been greatly expanded and the straight man has been marginalized to the point that, in exaggerated performance sketches, the two traditionally specialized roles no longer exist and only one character is left. This is the doubi, or buffoon, who has sunk far in terms of both intellect and restraint. The buffoon is easily led by naked primordial desire; the absurd, self-destructive performances of internet sensations like Luo Yufeng belong to this type. They cannot be considered humorous in terms of either intellect or discovery—or at least it is not a humor of any value or depth.