THE SINO-FUTURISM OF JOSEPH NEEDHAM

| February 20, 2015 | Post In LEAP 30

WHAT MIGHT A theory of history look like at this moment? How might art make forms that at least suggest a way forward? These are pressing questions now that we know this era is the Anthropocene, that epoch when the futures of both the social and natural worlds depend completely on each other.

There’s a lively debate in the Anglophone world about the future, most admirably stirred up by the revival of an accelerationist theory and art. For the accelerationists, there’s nothing for it but to say yes to the techno-capitalist enterprise, even as it transforms the human into something other than itself.

This meets a more classically Marxist critique, in Benjamin Noys’s book Malign Velocities and elsewhere, which insists that historical change depends on some kind of agency, in and against techno-capital, which can negate and transcend it as a historical stage.

It seems to me that both the accelerationist affirmation and its negation are missing something. Both rest on a kind of prior theoretical move, which then remains largely unexamined: both separate social history from natural history. Natural history becomes a sort of neutral background, a mere environment or resource for social history.

This is why I think this debate needs to encompass two other positions, which I call inertia and extrapolation. There is a brilliant theory of inertia in Jean-Paul Sartre’s now-neglected Critique of Dialectical Reason, a book that refutes most of today’s breezy accelerationist thinking even though written half a century ago.

In Sartre, natural history appears negatively, as a limit on collective social action in history. Worse, every attempt at a praxis to overcome this limit and the scarcity it imposes hardens into a mere world of things, what Sartre calls the practico-inert. Our attempts to make history are fractured by the residues of past attempts to make history, which force us back into passive and solitary forms of action, or what Sartre calls serialism.

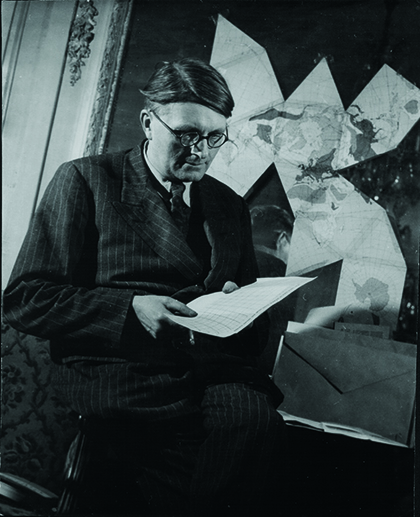

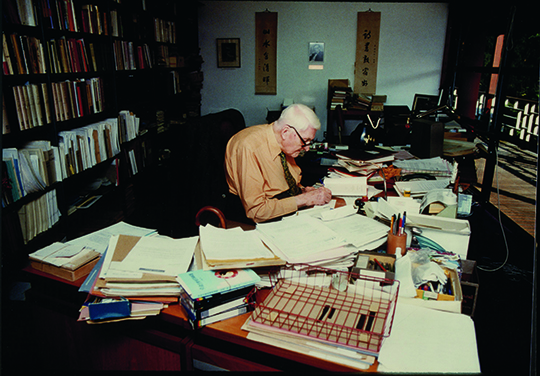

But what would an affirmative approach to natural history look like? Here I think we need to turn to thinkers even more neglected than Sartre. In particular, we could do worse than study the work of Joseph Needham: biochemist, embryologist, diplomat, historian of science, radical Christian, polyamorist, and lifelong friend of China.

Needham’s scientific work is relevant here because he was part of a movement that tried to work out what lay between chemistry and biology. In the 1930s this was a lively field, which started to map the sort of architectural forms that complex molecules could form, and how living things assemble themselves as a kind of higher-order organization out of these building blocks.

Needham realized that mechanical models would no longer suffice to explain the biochemistry of life, but he was strongly opposed to vitalist theories of life as having some magical added property beyond scientific investigation. This is an important moment in the history of science and philosophy to recall, given the popularity in our time of new forms of vitalist materialism, which want to revert to the sort of metaphysical thinking Needham and his collaborators dispensed with seventy years ago.

Equipped with the beginnings of a biochemistry of life, Needham then studied how the embryos of birds and reptiles grow. Here he turned to field theories, which understood the development of the form of the organism as a result not just of chemical processes but also of their location in a field structured around organizing nodes. This was about as far as the actual biochemistry of the late 1930s could go in thinking complex organization without invoking magical vitalist notions.

Needham’s scientific achievements were enough for a lifetime, but he had a second career as a historian of Chinese science and technology. In the 1930s, he fell in love with a Chinese graduate student, with whom he and his wife formed a lasting three-person household. He added Mandarin to his many languages and became an advocate for China, which was, at the time, under Japanese attack. The British government sent him to China on a diplomatic mission, charged with trying to help Chinese scientists and scholars, who were a particular target of the Japanese military.

And, of course, he fell in love with the place. He traveled over 13000 kilometers. He conversed with leading scholars, collected books, and even met Zhou Enlai, who would become the first Premier of the People’s Republic. What struck him was the way the Chinese seemed to have invented pretty much every practical technology, from plant-grafting to suspension bridges to toilet paper, many years—even many centuries—before the west.

After the war, Needham sat down to write a history of Chinese science and technology, a project on which he would spend the rest of his life. It is an acknowledged classic of western sinology, but our interest in it lies elsewhere. Needham had an even larger project in mind.

It is a question of worldviews. Needham thought that, in the west, there had been two dominant positions. The first stems from Plato, and posits a more real idea or form above and beyond the observable. The vitalism he so opposed is, via many twists and turns, a descendent of this worldview.

The other worldview comes from Epicurus, and sees the world as reducible to atoms. Order emerges from the random collisions and collusions of atoms. The Platonist worldview is something of a priestly view of the world; the Epicurian one is the worldview of the merchant or trader. This is not surprising, given that the ancient Greek world was run by both.

Modern science got going when researchers tried to actually discover the hidden idea or form behind appearances, but then had to make more use of atomism to actually explain it. Newton was motivated by a kind of Platonist faith, but actually described the world in atomist terms. That kind of mechanistic worldview had worked to get physics going, but it didn’t work so well for biology.

This is why Needham turned to what he called organicism. He got it partly from Marx and Engels, partly from Alfred North Whitehead, and partly from the early systems theory of Ludwig Bertalanffy. In this worldview, the world is not defined by a hidden idea or random atoms, but rather nested levels of organization, each with discrete material constraints and possibilities. The organizational affordances of physics give rise to chemistry, chemistry to biology, biology to social forms. Each is constrained by the level below it, but is not otherwise determined by it or reducible to it.

What fascinated Needham about China is that its ancient thought was already organicist. A civilization built not on coastal trade but on hydraulic engineering had been way ahead of the west in thinking organizational form all along. The future, Needham thought, belonged to organicist thought and action. The future, in a certain non-chauvinistic sense, might even be Chinese.

Needham’s great project was not just to understand biological organization or the past social organization of China, but to extrapolate from that knowledge to address the pressing question of what present and future social organization could be. Other levels of organization, or past social organization could suggest possible forms—in a non-deterministic way.

This is a crucial task for the Anthropocene. We need a speculative theory and art of possible forms for a human history that is nested within natural history. We need a way to think of organization that is not reductive, and certainly not one that projects social ideologies onto nature, as if nature were already a business model. Thus, of the four models of historical thought— acceleration versus negation, inertia versus extrapolation—it is the last of these that needs advancing. It points towards one or many worldviews, each of them new but partly old.

This has to be a collaborative project, not just across cultures, but across different kinds of knowledge. And here Needham himself is a great model of how to work. Theory can’t pretend to be a higher mode of thought than technology or science. If there’s a role for art it is interstitial, as a way of moving ideas between fields of knowledge. The great collaborative project, as Needham well knew, is to design and build a higher level of organization, where the futures of the natural and social worlds affirm rather than negate each other.