MIAO YING AND THE FIRST GENERATION OF CHINESE NET ART

| March 12, 2015 | Post In LEAP 31

TEXT / Ophelia S. Chan

As much as the internet is a utilitarian space for social movements, it is also a cultural space for personal and collective expressions of social issues.

BORN IN THE 1980s—China’s Generation Y—artist Miao Ying grew up in the era of Reform and Opening, when the domestic space of the home held optimism and aspirations for the future as digital media and technological devices became increasingly accessible to middle-class families. First there were air conditioners and microwaves, then personal computers and the internet. In the late 1990s, access to the internet was expensive for the average family, but it soon became a popular topic among young people and was much more accessible by 2000. In the 1990s there was a real sense of anonymity online—something impossible in this day and age of social media. By communicating in chat rooms and bulletin board systems (BBS), internet users could talk to people around the world in real-time and drop out of conversations and disappear offline almost instantly. This is what Miao initially found most intriguing about the internet.

Miao received her BFA from the New Media Art Department at the China Academy of Art (CAA) in 2007, and an MFA in Electronic Integrated Arts from Alfred University’s School of Art and Design in 2009. She found her time at CAA particularly inspiring: together with artists like Lu Yang, Miao belongs to the first group of new media students in China to be tutored by pioneers in the field like Zhang Peili and Geng Jianyi. The New Media Art Department, encompassing a wide range of disciplines from photography and video to animation and programming, offers a fresh approach to creative thinking, shifting the emphasis of training from refining technical skills to nurturing individual creativity.

In 2006, when blogs were popular and readers subscribed to RSS feeds on Xiami or Google Reader, Miao came across a post on the popular group blog Boing Boing that inspired her to make Blind Spot (2007), her first work to specifically address the conditions of the Chinese internet. The thread of posts addressed the Great Firewall, the complex system of internet content control in China, with a list of terms of government- censored search results on Google.cn; Miao decided there and then to use the preparation time for her university graduation project to compile a complete list of censored terms by searching for every entry in the Contemporary Chinese Dictionary—word by word—on Google.cn. This list, which took three months to complete, was then transformed into a “Revised Edition” with scans of the censored words, first shown as an installation in the United States in 2010—the same year Google’s search sites became inaccessible in mainland China.

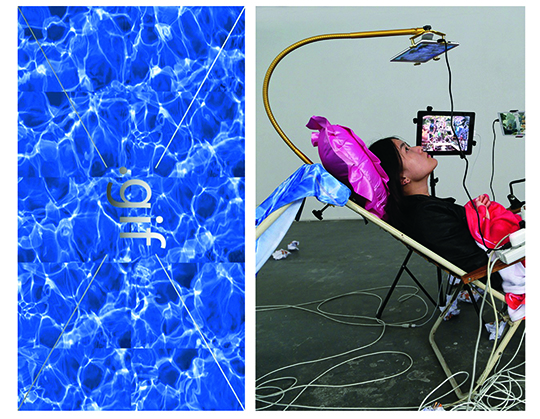

Miao Ying’s work, as exhibited in the recent V Art Center solo show “.gif ISLAND,” has a distinctive aesthetic and sense of humor; with lo-fi visual elements and a self-deprecating and witty commentary on contemporary digital culture, her works embody the essence of “Chinternet” aesthetics. In a series of animated GIFs, “LAN Love Poem.gif” (2014), screenshots of websites censored in China—Google, Facebook, YouTube, Twitter—are overlaid with animated three-dimensional typography for phrases from internet culture that resemble short poems: “Holding a kitchen knife cut internet cable, a road with lightning sparks” and “When cigarettes fall in love with matches the cigarette gets burned.” These visuals are accompanied by the soundtrack of Lionel Richie’s “Hello,” referring to the many memes and other derivative works based on the plot of the music video for the song, which famously tells a story of love between an art teacher played by the musician and a blind student who makes a sculpture of his head. This scene also inspires Miao’s work Is it me you’re looking for? (2014), a video in which the music video for “Hello” plays on YouTube in a subtle satire of the relationship between mainland internet users and the Great Firewall: the desire to reach over the wall and access the inaccessible resembles the proverb of blind men and an elephant, in which each man draws a different conclusion from incomplete information.

As much as the internet is a utilitarian space for social movements, it is also a cultural space for personal and collective expressions of social issues. The particularities of the meme form—catchy humor, simple imagery, remixed found materials—make it an accessible vehicle for political and social critique, especially in the context of China’s web censorship. Miao Ying’s recent online exhibition “Meanwhile… in China, so in love, will never feel tired again,” titled after the “Meanwhile in X” meme featuring absurd imagery of specific places, inaugurated the platform Netizenet with a series of six web-based works, including three animated GIFs and three posts on issues related to the Chinese internet environment. Far from an isolated wasteland, the Chinese internet evolves and grows within its unique limitations.

Miao Ying’s practice—particularly her web-based work—allows users outside China to get a glimpse of life within the Great Firewall in a humorous and accessible way. Works like iPhone Garbage (2014) are inspired by the website Bilibili, a popular video-sharing website in China on which user comments are overlaid directly onto the video in real time, such that the most popular videos are almost entirely covered. By turning commentary into content, the site creates a shared viewing experience among its audience. This technique of information overload is also a source of inspiration for Miao’s practice; she uses the term naodong, internet slang literally meaning “brain hole,” derived from naobu, or “brain supplement.” The latter term, which originated in Japanese anime subculture, once referred to using the power of will to make fantastic things occur in real life, but has taken on a more general meaning in Chinese—pure imagination. Naodong, on the other hand, indicates a gap in the mind for which imagination must compensate—a type of humor and temperament specific to the Chinese internet.

The internet both contrasts with and parallels daily life. According to Miao Ying, “Second Life is a game without a purpose. When people get together to participate in games for which they establish rules, you can pretend to be whoever you want to be—build things, make friends… but there isn’t a greater purpose, nor is anything at stake, which, to a certain extent, is like the internet itself. We can play different roles, interacting with whomever and whatever we want.” As she stresses, however, “We have to remind ourselves of our responsibilities as artists, and the fact that the most successful things might not necessarily be the best.” Internet art does not yet have a firm place in the history of Chinese contemporary art; in some ways, it remains separate from the umbrella of contemporary art. Even though more senior artists like Cao Fei and emerging figures like Aspartime have started to explore this field, there has been a delay in its popularization, lagging behind the development of global internet art. Miao Ying believes that the future of internet art in China is promising: whereas the nostalgia of Generation Y often conveys a sense of negativity, the next generation—artists born into comfortable and carefree lives in the late-1990s and 2000s—will be able to cultivate the genre because, counterintuitively, they lack the experiences and memories of a time when internet technologies were inaccessible.