KAO CHUNG-LI: BATTLEFIELD WITHOUT CORPSES

| April 1, 2015 | Post In LEAP 31

TRANSLATION / David East

Truth is the first casualty of the news industry.

Kao Chung-Li’s 1983 solo exhibition, held in Taipei at the American Institute in Taiwan—the only way to enter the art world at that time—revealed the intractable scars of the cultural Cold War. The exhibition, labeled a photo show, amounted to a political manifesto within this particular history. Kao began to consider himself a photojournalist in 1984; his practice of image creation by technical means (including all sorts of video cameras and other mechanisms for image circulation propelled by capitalism) endlessly tears apart, exposes, splits, and strips his subject matter, turning his eye back on the intellectual hegemony of image machines and machine images alike.(1) Kao focuses on the inherent violence of technology, echoing Lu Xun’s concerns around the slideshow incident in the early twentieth century. Starting out from a position of reflexive self-critique, he pledges not to remain in the shadow of colonialism.

Can Lu Xun’s infamous slideshow incident—during which he supposedly abandoned his study of medicine in favor of healing the mind and soul after realizing that those sound of body often remained powerless—be seen as a link between colonial visual regimes and the rule of modernity? Regardless of the authenticity of this anecdote, individual visual experience is undoubtedly a crucial starting point in inverting the rule of modernity brought about by colonization. But does adopting the viewpoint of the camera symbolize the completion of the process of decolonization? In colonized Taiwan, the awareness of the subject emerges in images between the landscape of the Japanization movement(2) and the Health Realism genre advanced by Taiwanese government film during the Cold War. Beginning with seeing oneself in the camera lens, this visual consciousness and the image production it involves are deeply embroiled in the alienation and lack of introspection of the photograph. Even as history textbooks marked the collapse of the USSR as the end of the Cold War, a new type of war was already raging on the intellectual and cultural battlefields of Taiwan.

AN IMAGE REPRODUCTION MANIFESTO

Kao Chung-Li recalls: “When I was a photojournalist, newspaper offices were categorized as manufacturing plants. This label clearly indicates that truth is the first casualty of the news industry.”(3) In 1983, he produced the photo series “Body and Soul,” acclaimed by fellow photographer Chang Chao-Tang as “a sudden clap of thunder in the 1980s.”(4) Though Kao wasn’t reluctant to leave video behind, he flashed past the camera lens like a bolt of lightning, authoring texts on the mechanical and aesthetic mechanisms of image production. Although he continued to “use the inherent characteristics of media as a starting point,” as in that first solo exhibition, he was increasingly influenced by his experience of covering the 1984 Haishan mine disaster as a journalist. When reportage and photography become an equation for the reproduction and consumption of disaster, the link between the truth of the image and the beauty of art must be critically examined.

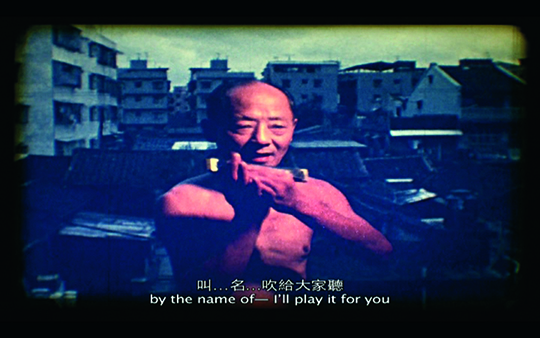

Starting from the Canon Super8 XL814 and then switching to the Fuji Single 8 ZC1000,(5) Kao won a total of seven Golden Harvest Awards(6) for his 8 mm “experiments, cartoons, and recordings” made between 1984 and 1988. The representation of time as a three-dimensional plane was an ongoing theme in his work, from the mixed-media work Unlimited Effect in his 1983 solo exhibition to the 1993 photo-essay “Home Movie: A Voice-Over of 8 mm Short Film,” written in the style of the Japanese I-Novel and published in the left-wing magazine Intermargins, and the 1988 prize-winning short film Home Movie. Reconstructed in collage, superimposed Polaroid, X-ray, photocopy, or Portrait of a Portrait of a Portrait, in which Kao’s father holds a portrait of his younger self, the artist’s scene extends endlessly behind and beyond the camera lens, like a wormhole in time created by the cycle of history: Kao himself becomes an interpretation of Roland Barthes’s metaphor of cameras as “clocks for seeing.” The aim of film is to condense past, present, and future, bringing about humanity’s “awareness of the imagination, memory, or knowledge” that film creates.(7)

Techniques that bring real and duplicate subjects face-to-face do not only allow the inherent characteristics and meanings of images to appear; Kao Chung-Li’s handmade mirror images also interpret the dual hegemony of knowledge and capital interwoven in time and technique from the unconscious point of view of the modern image, expanding on the multifaceted awareness of Lu Xun’s slideshow shock. At the seventh annual Golden Harvest awards in 1984, Kao’s experimental film That Photograph met with approval. Reproducing a shot of a crowd of people paying respects to a recently-deceased youth from Josef Koudelka’s 1963 photograph series “Gypsies, Jarabina, Czechoslovakia” and, using a technique that “converted the dimensions of an image into time and length,”(8) Kao creates a memorial space for a film industry undergoing digitalization. Projecting via videotape and an overhead projector, he is able to reverse time and movement, extracting a yearning for life from an image of death. As Henry Bergson notes in Matter and Memory: in unquantifiable memory, the past never ends; rather, a continuous state of affairs flows on.

TECHNIQUE AND POWER: WRITING WITH LIGHT

Kao’s sensitivity to video machinery and output formats comes from a critique of the continuing reproduction of colonial rule through the market economy of visual production. Taking his work as text, we find all kinds of not-yet-decolonized image properties. In 24 x 18. Half I, recently exhibited at the biennial held at the Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts in Taipei, an industry-standard 35 mm camera is transformed into a projector, transmitting a video composed of half-frame camera shots(9) of family life (mostly between the artist’s father and child). Since non-commercial film negatives are half the dimensions of camera negatives (24 x 18 mm rather than 36 x 24 mm), they are the exact same size of the costly half-frame film of the 1960s. Repurposing a 35 mm video camera as a projector reflects market strategies dialectically coexisting with the creative tactics represented by the half-frame camera, projecting a hazy frame-by-frame still montage. The project changes the course of a castrated industry into a mechanism for the control of emotions by means of the extra-diegetic image; by amplifying the sounds of the machinery with a microphone, it becomes incidental music for the soliloquy of the image machine confronting itself.

Kao Chung-Li once mentioned that, in 1966, Chen Yingzhen (under the pen name Xu Nancun) translated an essay on film titled “A Battlefield without Corpses,” critiquing Hollywood’s patriotic war movies for their legitimation and valorization of war. The essay was originally planned to be published in the fifth issue of Theatre Magazine, but, ultimately, “each issue was torn up one by one.”(10) That same year, the Organization of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa, and Latin America (OSPAAAL) organized the publication of the quarterly Tricontinental after hosting a titular conference in Havana, and, in 1969, Octavio Getino and Fernando E. Solanas co-wrote “Toward a Third Cinema,” published in Argentina. No one knew what the content of the essay on the missing eighth page of the fifth issue of Theatre Magazine was supposed to be, but the image of the ‘Battlefield without Corpses” may have beem expounded upon by these two South American filmmakers in their call for decolonization to fight the images of capitalism: “The battle begins without, against the enemy who attacks us, but also within, against the ideas and models of the enemy to be found inside each one of us.”(11)

This also echoes Kao’s Slideshow Cinema VI: An Autumn Afternoon, which discusses postwar machine-image aesthetics as a tacit mutual understanding of world order and the immovable presence of military force. The work targets the widely-praised Yasujiro Ozu through the work that best represents his quiet aesthetics: An Autumn Afternoon, which premiered in proximity to the signing of the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan, contrasting Ozu’s experience as a member of an infantry regiment handling chemical weapons with a Kodak Ektagraphic Audio Viewer Projector stored in the artist’s house and a series of shots depicting the richness of family life in postwar Japan. The artist bypasses the narrative as a background narrator, strengthening the intrinsic connections between image and text in public society and private spaces—the image is a ghost of colonialism that continues to operate on the body through capital just as Ozu’s influence on the aesthetics of machine images resembles the postwar economic miracle.

MELANCHOLY REALISM

Confronting the reality of the machine-image and the externally generated colonial history that developed the image-machine, Kao Chung-Li points out the interrelation of the material conditions of equipment and the aesthetics of image creation, taking Daidō Mori yama’s street photograph of a feral dog and the automatic function of 35 mm cameras as an example. Of course, this doesn’t stop the artist from working, just as Kafka did not stop writing in German simply because he was Jewish. My Mentor, Chen Yingzhen originates with the dual limitations of a sudden loss of funds and a miscarriage, and the fact that the techniques of the image had not yet been exorcised of colonial modernity. Kao, however, reproduces with a digital camera silhouettes that Chen Yingzhen originally filmed in 8 mm at a family party, pairing them with hand-drawn cartoons that explain the course of Chen’s life (including Rong-Zan Huang’s 1947 woodcut The Terrible Inspection, which symbolizes Chen’s coming of age during the 228 Incident, which launched the White Terror period under the Kuomintang government). This is art history taking its lead from Lu Xun’s New Woodcut movement, finding a way to liberate Taiwan’s blinded cultural history that has withstood the intrinsic belittling of colonialism’s steadfast belief in western modernity. This also corresponds with Chen’s answer (still under pseudonym) in an interview with his close friend, the painter Wu Yaozhong, titled “Man and History.” Discussing why Taiwanese painting bears traces of realism left over from Japanese colonialism while the Fifth Moon Society imitated Western abstract artists, Chen answers: “One condition of realism is the close connection of man and history … it can never see the world from individual, internal complications. Instead, it understands the world from the shared demands and desires of the masses.” In the opening and closing titles of My Mentor, Chen Yingzhen, Kao Chung-Li whistles “The Internationale,” resounding outside the reconstructed image but inside its memory. This is not an elegy for the “Battlefield without Corpses”; it is the language of resistance shared by the voiceless and oppressed.

(1) Kao Chung-Li, in the magazine Art Critique of Taiwan, describes the relationship between “image machines” and “machine images”: “Machine images are material, film is material, text is material. Image machines are material; the camera which breaks down time, space, and motion is material; the projector which returns time, space and motion to their original states is material.”

(2) Theory of Japanese Landscape is a recent Japanese masterpiece. By displaying the distinctive beauty of the Japanese landscape, it manifests a consciousness of Japanese national superiority and an awareness of colonial expansion.

(3) Excerpt from postal correspondence between Kao Chung-Li and the author, December 19, 2014.

(4) “Time and Body: Kao Chung-Li,” Chang Chao-Tang, January 25, 2013.

(5) These two cameras used 8 mm film, incompatible with the 35 mm film used by Hollywood for filmmaking and projection.

(6) The Golden Harvest Awards for Outstanding Short Films are held by the Republic of China Ministry of Culture National Film Federation, and encourage non-commercial films, documentaries, film experiments, and animations.

(7) “Picture of a Voiceover: Unconscious Theory of Light and Servants of Photography,” Kao Chung-Li, 2011.

(8) Kao Chung-Li stretched one part of the scene to cover the whole area, or edited the whole scene together with other parts of the image to turn the image into a 24-minute video recording.

(9) Most 135 film cameras are full-frame cameras, with one roll of film taking 36 shots; half-frame camera negatives are half the size of full-frame cameras, so one roll of film can take 72 shots, saving half the production cost.

(10) “Watching Time: A Solo Exhibition by Kao Chung-Li,” Kao Chung-Li, 2012.

(11) “Toward a Third Cinema,” Fernando, Solanas, and Octavio Getino, 1969.