PERFORMANCE AND EVERYDAY LIFE IN CONTEMPORARY CHINA

| December 23, 2015 | Post In LEAP 34

Protesting in front of the camera is not merely a demonstration; the resulting image could trigger another performance of protest at any moment. Facebook and other Internet media break down the relationship between viewing and performing, and transform its ritual nature into the repetitive behavioral patterns of the everyday. This new approach to the ceremony confirms the meaning of living today.

Performance in Contemporary China

The critical performing arts—from theater to performance—reveal the performative elements of everyday life. More often than not, this means exposing the power mechanisms behind the normative patterns of social behavior. Performing cultures in China have slowly evolved towards this deconstructive purpose since the 1980s.

Shanghai avant-garde theater practitioner and theorist Zhang Xian convinces us, in his article “Social Drama,” that, to understand the significance of alternative performance in China, one must take into consideration the fact that social life prior to the 1980s was controlled by and incorporated into the party-state apparatus.

With little space for people to freely deploy their bodies in social situations, they became “docile bodies” in the Foucaultian sense; they moved, functioned, and yielded productivity according to mandated social and political choreographies.

Theater itself was managed by the state, reinforcing the ritualistic and symbolic elements of everyday life on the stage.

The rise of avant-garde theater since the 1980s marks the emergence of bodies wanting to break out of these disciplinary demands. Mou Sen, Meng Jinghui, and Zhang Xian, among many others, started to create their own plays, apart from the mainstream of Henrik Ibsen and Konstantin Stanislavsky. Their practices primarily seek to make sense of what it means to be an individual in this new era.

It would take a book-length study to do justice to how these unofficial forms of performance have evolved, but this historical background allows us to consider the significance of contemporary Chinese performing cultures. We must think, first and foremost, about how new social spaces are opened up for new forms of performances to emerge. Free markets have brought about new social spaces, but themselves represent a new global neoliberal regime that codifies new desiring forms of bodies and behaviors.

The Rise of New Performance Venues

As the free market economy was implemented, state-run theaters faced financial crisis as the opening of market-driven performance venues enabled people to produce shows that were not explicitly state-sanctioned. However, as their commercial nature indicates, these venues often produce lighthearted romances and comedies targeting newly formed bourgeois audiences. Fortunately, there is a pocket of independent artists who insist on producing meaningful independent performances of the sort that reflect on the meaning of life, critically engage with normative behavioral codes, and reimagine the possibilities of public as well as private lives.

Zhang Xian still holds onto the notion of independent performances that can change lives. Unlike the pioneers of his generation, who mostly now lean towards the law of the market, Zhang and his cohort ran Downstream Garage (Xiahe Micang) as a base from which to produce independent performances and transdisciplinary festivals. Upholding social theater as a central credo, the performances produced there sought to destabilize the boundaries between performer and audience, inviting the audience to engage with social norms in a different light. After closing the Garage, these artists now try to continue their work through different venues, mostly art museums like Power Station of Art, Rockbund Museum, and Ray Art Center. Zhao Chuan and his Grass Stage troupe also make significant social theater in Shanghai, creating temporary utopian spaces in which amateur actors act out important issues of social inequality and exploitation in front of audiences from all walks of life and social classes.

In Beijing, the most significant independent performance venues is Penghao Theater, located next to the state theater school, the Central Academy of Drama, near Nanluoguxiang. Founded by Wang Xiang, Penghao positions itself as an incubator for new performing artists to create work as well as a node in the exchange network of global performance. So far, they have held six international festivals including artists and troupes from all over the world, who both present shows and hold workshops with local practitioners. Penghao has become the city’s main venue for immersive theater, environmental theater, theater as social action, documentary theater, physical theater, and psychodrama.

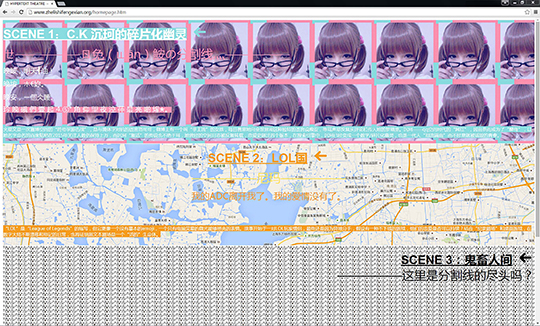

Much has been written on how the advent of digital space has changed social relationships, and the divide between public and private lives. In the contemporary Chinese context, we must consider these issues in light of the post-socialist historical condition. Theater artist Sun Xiaoxing has begun to think about the question of social space in the Internet era. Born in the 1990s, Sun’s digital drama Here is the Dividing Line turns cyberspace into a venue for performance, challenging participants to rethink interpersonal relationships and censorship in a public forum.

Networked space redefines our understanding of social reality. The fictions of the digital allow us to become more aware of the constructedness of our social norms, and often turn fiction into reality. If theater was once regarded as an inherently dangerous space to which the virtual could be safely segregated, then networked space is now the meta-theater of the contemporary world, an engine turning the possible into reality. Instead of using theater to look at issues of the digital, Sun’s work foregrounds the central question of theater as a medium—the dialectic between real and virtual, and how it enables us to think towards the meaning of a better life.

We are left with more questions than answers. Many must continue to be engaged: is this flourishing of alternative performance cultures indicative of the emergence of civil society in contemporary China, or is it simply a consequence of the free market that testifies to the commodification of cultural life? As life becomes more performative, we must treat theater as a serious field of knowledge production, one that pushes us to face ontological questions of being, epistemological question of reality, and ethical questions of acting.