Spirited Away: the Shifting Landscape of the Art World in 2020 from London, Berlin, New York to Los Angeles

| March 5, 2021

As life was disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, Sammi Liu, owner of Tabula Rasa Gallery, and artist aaajiao (Xu Wenkai) have been stranded in London and Berlin respectively. Author Danielle Shang who lives in Los Angeles and curator Weng Xiaoyu at the Guggenheim Museum in New York have hunkered down for nearly a year, unable to travel. Each of them has witnessed a tumultuous year in the world from a different perspective. At the beginning of the New Year, the four of them congregated on Zoom to chat about their experiences in the past year, as well as their reflections on the shifting landscape of the art world.

Aaajiao (A): Around this time last year, a stranger called me “China virus” on the street in Berlin. That was the first time for me to experience contempt from ordinary Europeans. I knew it was not an isolated incidence, because there had been several attacks on East Asians. Li Zhenhua, Hu Xiangyu, Du Du, Wang Jiangnan and I took to the street to protest, holding signs that read “Fear Eats The Soul,” “Racial Discrimination and Self-Discrimination Are the Real Viruses,” etc., in a hope to band together with other minorities.

Danielle Shang (S): Attacks on East Asians in the US are common too, especially at the relentless instigation of the previous president. The Asian Diaspora in the art community therefore organized a grassroots coalition Stop DiscriminAsian. [1]

Last year, we saw racism and inequality intensified. Guggenheim was at the center of criticism. Xiaoyu, what are your opinions on the museum’s union workers’ picketing over labor exploitation, the forced departure of Mortimer D.A. Sackler from the museum board after Nan Goldin’s campaign exposing the Sacklers for their role in the opioid crisis, chief curator Nancy Spector’s resignation due to her allegedly suppression of a black curator, and the appointment of Naomi Beckwith, a black curator, to replace Spector?

Weng Xiaoyu (W): First, I’d like to clarify that the Metropolitan Museum of Art was at the center of the Sackler scandal. But of course the family has donated to many museums, including the Guggenheim. I’m aware of the external criticism of the museum; however, the museum is just a microcosm of the American society. For example, the racial challenge: regardless how people of color argue, white people’s view of the world was instilled in them at the birth. It might not be their intention to hold prejudices, but the social structure is based upon wealth accumulation, which predetermines white people’s innate privilege and others’ disadvantage. “Empathy” is the trendiest keyword for the time being. But empathy is very limited; at best, it is no more than acknowledging minorities’ hardship. What is then?

S: Sympathy is probably more accurate. To empathize, one not only acknowledges the hardship, but also experiences it and shares emotions from the same perspective, which is almost impossible.

W: A white man makes a 10% effort to do something, and he receives 200% feedback, whereas a person of color has to make a 1000% effort to accomplish the same, but receives no attention. If we disregard social mechanism, identity, race, upbringing, and wealth basis, universality is an absurd premise. However, the privileged wealthy elites want to spin their argument with this hypothesis.

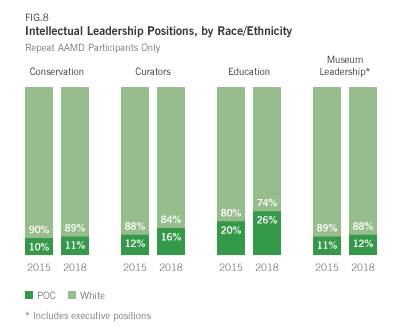

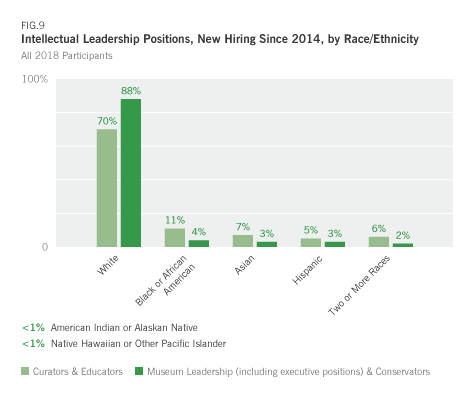

All museums talk about diversity and representation of non-white-male artists. However, there’s a traditional power relation between artists and curators: curators are the gatekeepers who decide whom to represent and what to show. The current gatekeepers are mostly white men. When a white curator shows black artists, they think highly of themselves for making contributions. But it is impossible for them to yield the power of decision-making to people of color. It is rare to see a black curator curating a white artist’s exhibition. In general, black curators curate exhibitions of black artists; Asian curators curate exhibitions of Asian artists, while white curators can curate everything. In the end, discretion and authority are still in the hands of white people.

Sammi Liu (L): In the British art community, class division is ostentatious. When Nicholas Cullinan became the director of the National Portrait Gallery in London, the public derided him as “the toilet guide,” because he was employed as a visitor services assistant, when he was in school, and sometimes he gave directions to the toilet to visitors. The actual reason for the ridicule is that he attended the public high school. In the British cultural circle, attending a private school and being born in the upper class are necessary conditions for a museum director. His advanced education and work experiences at the Guggenheim, the MET and the Tate are all dismissible. The audience of this museum consists of conservative British aristocrats, who, in their mind, can’t admit people from a different class to be their director.

S: Class disparity and economic inequality are instrumental for the thriving of the art market [2]. For this reason, mega galleries recruit interns and employees from the wealthy and upper class. For example Gagosian hired artist Ed Ruscha’s daughter from outside his marriage and the daughter of billionaire/super collector Steven Cohen. Their families are on the boards and councils of large museums, dictating museums’ operations. It’s not surprising, when the Art Newspaper reported a few years ago that, over all, 30% of the solo exhibitions of 68 American contemporary art museums were for artists represented by the five mega galleries. 11 of the 12 major exhibitions at the Guggenheim in seven consecutive years were for artists represented by the five galleries. The ration for the same period at the Museum of Modern Art in New York is 45% [3]. In 2020, this trend of winner-takes-all is even more flagrant. The reason behind it is clearly capital accumulation.

L: The disparity is getting worse. Many galleries in London are shutting down. Even Marian Goodman closed her London space.

S: In contrast, new galleries are sprouting in Los Angeles. For example, Rele Gallery from Nigeria, Half Gallery from New York, and CLEARING from Belgium all opened their outposts. Chris Sharp moved back from Mexico City to open his Los Angeles space. How is the preparation for your London space?

L: Still in progress. I have been investigating the art scene in London for the past year. Before, I only learned about London galleries from Frieze Art Fairs. The galleries that did not participate were not on my radar. Now I have discovered so many interesting small galleries in London. At least 20 small spaces have caught my attention. There are also non-profit and alternative spaces, which have existed for a long time, occupying a pivotal space in the local art community. There is at least one in each neighborhood, serving residents, students and art lovers. Both their quality and reputation are very good. Such as Chisenhale Gallery, Peers UK, Heni Group, Delfina, etc.

The art ecosystem here is diversified and healthy: not everyone is madly after money. Of course, government funding and various grants provide basic financial stability. If citizens benefit from the free, non-profit space in the neighborhood, they are much more willing to financially support the space when it’s economically possible.

I hope to be able to organize in London exhibitions and projects with a focus on Asia that cannot be realized in Beijing. But there are very few Chinese in the UK, and even fewer in London, so I understand that it makes no sense to simply parachute an exhibition of a Chinese artist. The exhibition needs to have local relevance.

A: There is no interest in Chinese or Asian artists in Berlin either. It’s easier for a queer artist to make it, for they have a community. Ironically, Europe is very eager to tap into our resources and the market back in Asia. Galleries here do not necessarily represent Asian artists, but they all employ salespersons who can speak Chinese. This is what they call “cultural diversity.”

W: The same logic exists in the US. Now the curiosity about Chinese artists has long gone, and the anti-Chinese sentiment is skyrocketing, but museums all hope to attract money from the Chinese.

S: The sinophobia is quite preposterous. When The Week In Art (the Art Newspaper’s podcast) reported on the Shanghai art fairs, the host absurdly suggested Western galleries to take the opportunity of being in Shanghai to condemn China’s policy in Xinjiang [4].

The Chinese artists have fallen out of favor. Black artists now are in demand. In order to perform a gesture of cultural diversity, museums have begun to scramble for works by black artists, especially paintings. The art market has turned into a feeding frenzy. Some black artists could only produce 10 paintings a year, but 100 museums are lining up. As a result, not only prices are dramatically inflated, but also it robs private individuals the opportunity to collect from the primary market. Consequently, the collector has to spend a fortune in the secondary market, which in turn exacerbates the spike of prices in the primary market. It is unprecedented for museums to conspicuously compete in the market, which incites the vicious circle. Last year, the epitome of shooting to stardom overnight was the case of Amoako Boafo.

A: I think, the chaos has made the rule of the game more transparent, revealing the close relationship between institution, art and capital. No one is in it purely for the sake of art; everybody is participating in the game of market transactions and art productions for power and profit. I know that some artists, such as Julie Curtiss, sell very well and are desperate for institutional validation, so they demand collectors to donate their works to museums, but museums don’t want them. It’s not just one party who speculates, but the entire system functions in this economic structure. The pandemic has compounded its magnitude and speed. When the step of physically viewing exhibitions is skipped, the only thing left is the naked monetary exchange based on a PDF. What a shameless theater! We are all actors in this, and we all understand that the cost of the game is very high: the market will influence the content of the gallery to quickly move towards conservative values of investment and decoration. We will regress at the end.

L: The hype around black artists reminds me that western museums have advocated supporting female artists for many years. The Baltimore Museum of Art, for instance, has promised to only collect works by female artists in the next five years. Some people question whether it is overreacting. However, according to a recent survey by In Other Words in conjunction with Artnet News, only 11% of collections and 14% of exhibitions in the 26 largest US museums in the past 10 years are works by female artists[5]. Similarly, only the final data can tell whether we go overboard with black artists.

The Black Lives Matter movement has given me an opportunity to pay attention to the activities and related creativities of black artists. For example, in the summer, I visited “We Will Walk: Art and Resistance in the American South” at Turner Contemporary in the UK. The show toured from the MET and presented works by black artists not in the mainstream in the American South. My overall impression is that quality exhibitions of black artists and minorities are far from enough.

We were educated in a Western-centric system, and there was no “need” to investigate non-Western cultures and histories. Because of this movement and this exhibition, I began to look into materials that underline their historical backgrounds. For example, James Baldwin and Toni Morrison. Before, I only knew of their names, but was oblivious to their writings and theories. Now I finally have an opportunity for self-education.

Nowadays, works by many black artists look alike. I hope to learn about their backgrounds to better tell which artists are more imitative and which are more genuine.

S: Lately, American institutions and galleries have shown a great number of black artists, and hired a lot of black directors and curators. Whether a gesture or not, It is undoubtedly a positive thing. My concern is that if the black identity is singled out as the criterion for collection, exhibition, and promotion, other people of color will be even more excluded, marginalized, and left with even fewer opportunities. Latinx artists and Native American artists, such as ASCO and Slanguage, have stood in solidarity for many years to fight for equal rights for exhibition and representation. Rafa Esparza turned his solo invitation from the Whitney Museum into a collective presentation of several Latinx artists. Will their voices now be buried?

Asian artists are relatively quiet. An Asian gallery owner in Los Angeles was hoping to organize a group exhibition of Asian artists in the summer and donate all the proceeds to black social movements. But in the end, the gallerist gave up out of the fear of being blamed for opportunism. Korean American writer Cathy Park Hong in her book Minor Feelings explains, “Asians lack presence. Asians take up apologetic space. We don’t even have enough presence to be considered real minorities. We’re not racial enough to be token. We’re so post-racial, we’re silicon.”[6] I remember, in 2017, to maximize profits United Airlines oversold seats and used violence to force a 69-year-old Vietnamese passenger off the plane when the aircraft was full. Why did they single out an old man with an Asian face among all passengers? And how could they brutalize him into a coma under all eyes? Are we Asians not model immigrants? Hong’s explanation hit the nail on the head, “Chicago aviation officers thought, He is not any man, he is a thing. They sized him up as passive, unmasculine, untrustworthy, suspicious, and foreign.” [7] The endless brutalizations targeting Asians since the outbreak of COVID-19 accompanied by the apathy from the public and politicians attest Hong’s statement.

Additionally, in order to lip service black artists or posture for political correctness, no one criticizes bad works by black artists. Isn’t that counterintuitive?

The Tate organized an exhibition of African American artists “Soul of Nation.” Ironically, it failed to land a major museum for its tour in the US. Only second-tier museums and private museums picked it up. Nevertheless it became a social media sensation.

W: This exhibition that was centered on identity may be the best received of its kind in recent years. The reason for its sensation was that it arrived at the right time and the right place in the United States, at the height of the black movement for justice. The relationship between the United States and Europe is inextricably linked. American culture is ultimately a continuation of European culture. The United States is secretly feeling culturally inferior. Many art institutions love to hire Europeans curators and directors. Under the guise of cultural diversity, they bring in Europeans to be their gatekeepers. Such is the rule of the game: Americans go to Europe for the shortcut to unwarranted credentials, and vice versa. But their game excludes Asia or Africa.

A: What they want from Asia is Asian capital. In fact, it is still a colonial ideology, although it looks very civilized on the surface.

W: Another important point is the continuity of religion and belief system. Europe, the United States, and former colonies in Latin America form their power structure based upon this genealogy. The second foundation is class and capitalism. These two arteries are instrumental for the paradigm of today. Everything is structured within this network and following this logic. Skin color is a fabricated subject and a token. We can superficially debate anything, as long as we don’t touch these two major arteries.

L: I am currently reading The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution. The author Dan Hicks proposes a radical idea, which is to return all looted Benin cultural relics to their original places. According to the author, the discussion on repatriation has been around for half a century, but in the end it still remains futile. It is time to take a radical step. However, this idea cannot be discussed in the UK at all, as it is castigated by the British upper class. They find excuses in Africa’s economic instability, war and dictatorship for holding African artifacts hostage. The British assume the moral high ground to “help and protect” the world’s cultural heritage.

There is a Decolonizing Arts Institute at the University of the Arts London [8]. They give grants to minorities for research on decolonization in various areas. I think the game needs to change at all levels, but how to do it and to which extent remain questionable.

W: Speaking up is not the same as being heard. There are many similar grants and positions related to decolonization research. Many people are creating contents—very meaningful contents—but without any social impact. Their voices are in an empty echo chamber with no actual effect. What is needed now is a platform to be seen and heard. Small noises are no problem; however, if we demand for a large platform, we would be told that we are not qualified and do not meet the institutional standard. But who is qualified? The ones represented by blue chip galleries? Who decides the standard? After all, it comes down to authority and the glass ceiling. I think the only way to make a paradigm shift is to completely deconstruct and reconstruct from the ground up.

Weng Xiaoyu in New York, Sammi Liu in London, aaajiao in Berlin, and Danielle Shang in Los Angeles in January, 2021

Transcribed and edited in Chinese, and translated to English by Danielle Shang

Notes:

1. stopdiscriminasian.org

2. William N. Goetzmann, Luc Renneboog and Christophe Spaenjer. Art and Money. Yale School of Management Research Paper Series, International Center for Finance Working Paper No. 09-26. 2010

3. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/almost-one-third-of-solo-shows-in-us-museums-go-to-artists-represented-by-five-galleries

4. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/podcast/where-art-fairs-still-happen-the-shanghai-buzz

5. https://news.artnet.com/womens-place-in-the-art-world/womens-place-art-world-museums-1654714

6. Hong, Cathy Park. Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning. United States: One World, 2020. P7 & P18

7. lbid, P33

8. https://www.arts.ac.uk/ual-decolonising-arts-institute