Unsettled Consciousness

| March 30, 2021

At the end of last year, the author conducted informal interviews with curator Angie Nee, artists Andong Zheng and Furen Dai, respectively, on the loosely connected concepts of overseas study and work, identity politics, and (reverse) cultural shock. Their practice as artistic and cultural practitioners were discussed, as well as various subtle situations, thoughts and feelings evoked by their experience in studying and working overseas.

Angie Nee is a curator. She received her master’s degree in curatorial practice at the School of Visual Arts in New York. She currently lives and works in Shanghai.

Zheng Andong is an artist who obtained a master’s degree in Fine Arts from the Photography Department of Rhode Island School of Design. He currently lives and works in Shanghai.

Furen Dai is an artist and researcher, currently lives and works in Boston.

Yam Chew Oh,《A Possible Way Forward》,2018,foundwood,plastic,pedestal and glue,Approx. 35.25 x1.5 x 16 inches

01

This January I came down with a bad cold. I rarely get sick, but in that small, Brooklyn apartment, I was forced both to endure the pain of a swollen throat, and to watch a string of words like “Huanan Seafood Market” and “infection” popping up in my newsfeed—all while looking for plane tickets home, back to the northern part of China. The inspissation of Chinese New Year atmosphere, friends’ visits, a plan to travel to the UK during a break from my internship—all these plans made such news seem as distant, and unconvincing, as other discomfiting news in the past.

At least half of my plans were realized: After a relaxing trip to the UK, I reached home on time, to celebrate Chinese New Year with my family—accompanied by an increasingly intense war of the news on the suspending contagion, between official and popular discourse. My mother continued to assert, confidently, that I was overly paranoid, and had exaggerated the severity of things; she overruled my decision to book a flight back to New York ahead of the scheduled one. Only on the day I returned home (January 21), did official sources confirm that “a novel coronavirus can be transmitted from person to person causing pneumonia.”

What followed was upsurges of upsetting news that was difficult to face, mentally and emotionally; and to someone who had happened to have just left the place “where I should be,” a huge shadow also settled over me: would I be able to return to New York—and should I?

Of course, this question was quickly rendered moot by the travel ban issued by the US government to nonpermanent residents seeking to travel between the States and China[1] (dozens of WeChat messages and calls from friends failed to rouse me quickly enough to change my flight). So, in the next twenty or so days, I stayed home, working remotely, and trying to formulate a contingency plan for returning to the States. From the beginning of the outbreak until now, the small city where I live has not reported a single case of coronavirus.

02

Towards the end of February, faced with a US border whose reopening seemed a distant prospect, I decided to play Benedict Arnold—flying, with stops in Dubai and Barcelona, to Mexico, then Cuba, each of which I would visit for one week, before returning to New York. As I traveled to these places, the “time lag” present in different countries’ responses to the epidemic became increasingly apparent. The rigorous lockdown and testing policies enforced in Mainland China go without saying—but compared to the vigilance with which Cuban airport staff interrogated me, at length, Mexico seemed relaxed, almost complacent, and the customers at the airport hotel buffet in Dubai showed no signs of anxiety.

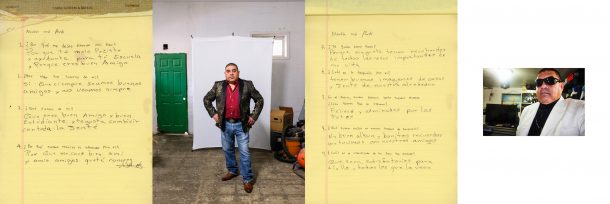

Gyu Ho Park,《Martin #3,#4》,“New York Guide” series, 2020,photography installation, flexible size

Thrown into a crowd of busy travelers of different backgrounds, as well as the locals of different stripes, I suddenly felt that my return trip might not at all an emergency—nor was it necessary. Only the frequent takeoffs and landings spurred my sense of “the immediate existing”; I must have had a different expression each time I was required to show my passport. When I eventually reached US customs, on March 1, after giving me my entry stamp, the employee behind the counter said, “You look so nervous.”

I believe that at the time Angie Nee was just as nervous—when there was less than two months to the opening of her graduate exhibition “Floating”, which she was then curating, the outbreak had begun to spread rapidly and predictably on the East Coast. Under such pressure, the Curatorial Practice department of the School of Visual Arts, where Angie was studying, ultimately made all its six graduate exhibitions online only, resulting that the questions surrounding “Floating” also fell into a state of strange, irresolvable contradiction.

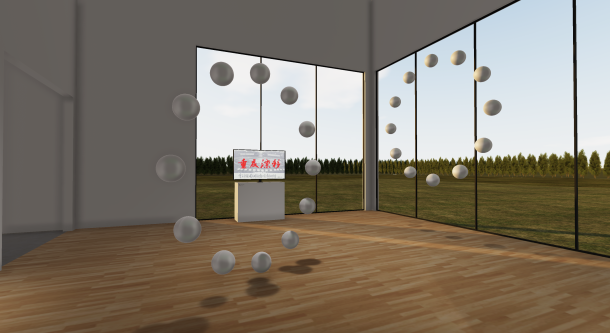

“Floating”,online exhibition, installation view,School of Visual Arts,New York

Constant transits from childhood to adolescence, the ability to adapt swiftly to new situations, and an acute sensibility to the changing environment as a result of living in different places, all thread through as clues in Angie’s curatorial work. She is constantly alternating between observer and participant, a reflexive role-switching that seems to continuously run through the exhibition: when artist Wei Tao released dozens of white balloons in Manhattan, using the drifting paths they took between skyscrapers a kind of metaphor for the artist’s own, provisional identities of international student and freelancer; when Yam Chew Oh scrutinized his family history carried by Karung Guni (believed to be a Malay phrase; according to one saying, it is a portmanteau of the Malay for “burlap sack” and the Fujianese for “milk.” In today’s Malaysia and Singapore, Kaarung Guni refers to used-good resellers who make their living buying used metals, cloths, and household appliances) and turns it into a installation consisted of light green plastic bags and a metal ring, finally “hanging” it beside the foreword written on a virtual exhibition wall; when Korean artist Gyu Ho Park, who grew up in his father’s factory, learned about the accidental death of a worker he’d once photographed in Queens slaughterhouse, and promptly decided to hand the camera he took with him during impromptu visits to the factory to the workers, and to appear himself in front of the lens; when Furen Dai finished interviewing fifty immigrant families, then took questions she’d heard when applying for a US visa and various immigrants’ responses to them and writing them on traditional Chinese lanterns…

Wei Tao,《Balloon in the city》, 2019 , installation with environment, flexible size

After a virtual walk-through of the exhibition with Angie, I met with her in person two weeks ago in Shanghai. The few Chinese artists who’d appeared in her show had all returned to China by this time. Angie mentioned her feelings now when watching international news: the first was, “Good thing I’m back.” The second was, “What about the people who are stuck there? What can they do?”

In all fairness, this is probably a common state of mind—at least to people like Angie and I, who’d undergone the identity transformation from “Chinese folks trapped in a foreign country where they are subject to discrimination” to “international students studying in the US who spent huge amounts of money and go through a whole gauntlet of obstacles just to return to China.” We stood at a crossroads in Shanghai that had largely regained its order, waiting for the light to turn green; and what tied to each passerby’s arm was a disposable mask whose symbolic content already exceeded its practical value.

Just as I found myself thinking, irresistibly, of making these quick adjustments to one’s identity, wondering which identity was more pressing and noticeable, which was more difficult to perceive because of its vastness, its complexity, and its resistance to discussion, Angie suddenly asked me: Do you ever feel like you’re afraid to run red lights in Shanghai?

The skyline of New York City

Our memories had dovetailed to New York, where running red lights is rather common. And just as the obvious truth displayed by her exhibition, sojourners are unable to perfectly, wholly “be here,” wherever here may be. When it comes down to it, individual experience was obviously not a minor historical footnote, but rather the model, and its many variants, for a kind of planetary state of being. After all, during this year in which travel has become nigh impossible, who can we encounter, other than our own selves, which once stayed in many places, and wrote self-ethnographies tirelessly and in every way possible (including via the other)? And even if we share the same labels as other people, when we think of all the changes we are always undergoing, thanks both to the outside world and our own bodies, is our homogeneity still assumed to be so simple, obvious, and ineradicable?

03

My photographer friend Zheng Andong, is still working on his photography series, A Chinese Question.

In many ways, Andong is far from the typical international student pursuing a fine art’s degree: after spending four years obtaining an undergraduate degree unrelated to art, he spent the initial period of his MFA experimenting, and during the school critiques, the question always seemed to be “where to find material, and how to justify the work.” He once told me that to his American and European classmates, his connection to General Tso’s Chicken—an American Chinese fast food staple—was perhaps much stronger that he’d imagined. Yet what, after leaving his campus, or the circle of overseas Chinese artists, was his “Chinese question”? The crux of the question (and the answer) seemed far less simple than the negative American stereotypes about Chinese migrant laborers and blatant anti-Chinese sentiments, pointed to in the political cartoon The Chinese Question, published in 1871.

Andong Zheng,《The Chinatown Motel,Nevada》, 2018, fine art inkjet printing

Filled with curiosity and suspicion about the “ways that Chinese people are seen and conceived of in the United States,” Andong began to travel across and photograph the American West in 2018. His explorations began from the cities and towns (including many ghost towns) bordering the western part of the erstwhile Central Pacific Railroad, and then extended to the mining towns and camps that still bore traces of Chinese laborers. The history of Chinese laborers building the Central Pacific Railroad in the 19th Century gave his journey a certain heaviness, a certain romance, yet when he drove solo along the interstate highway, tracing a path that more or less paralleled the railroad’s, or even on backcountry roads built on the actual roadbed of the former railroad, “the goal of searching for ’Chinese-ness’” seemed to dissolve into the strangeness of his proximity to this “historical origin”—even though, in Nevada’s mining towns, he was still overenthusiastically called “Chinaman” by gas station attendants.

The livelihoods of these Chinese railroad workers from 150 years ago, and Andong’s search for the evidential traces of their existence seem like two, parallel timelines, unfolded through the repetition of old pictures and satellite maps. The artist shuttled between different, still-recognizable gathering places for former railroad workers. He inspected the leftover platforms, cuttings and embankments near such ghost towns; collected porcelain fragments and Qing-dynasty copper coins scattered somewhere in the desert; gazed at the traditional lanterns, shrines and decorated archways inside a bar called “China Sea”; and even tasted the shrimp dumplings that a cowboy who housed him for a night brought out, miraculously, in the morning… These symbols, packed with East Asian connotations, finally lined up to form a kind of one-directional transparent screen, constructing a barely visible “Chinese past” through archival documents, theory, and language, but also foreclosed the possibility of using it as a point of reference for clarifying one’s hazy experiences of identity in the complex, present reality.

Andong Zheng,《Promontory,Utah》, 2019, fine art inkjet printing

As a kind of sustenance for the seriousness and arduousness of his trip, Andong pursued livelier interests that came along with the ritual of “going west”; and it was this sense of fable, incomprehensible without firsthand experience, that connect Self Portrait—A Chinese Cowboy and The Oriental Poppies in Tuscarora, Nevada.

Andong sought out the original site of a photo taken by Alfred A. Hart, the official photographer of the Central Pacific Railroad, in the late 1860s—Palisade Canyon, located more than 400 miles away from Sacramento. In order to “re-stage” the photograph, he surveyed the site, and then climbed the mountain twice, setting up an outdoor studio and camera mount on one of the peaks, then placing himself into the center of the composition. On the day of the shoot, fog and remaining mountain fires make the rock surfaces, roads, and occasional dried-up riverbeds glimpsed within the finished work seem even more untamed; much like the wild loneliness of the dense vegetation, there were few signs of habitation around the canyon. When the photoshoot finally ended, a Chinese mother and daughter who happened to pass him on the road doubled back, to give him two honey peaches.

Andong Zheng,《Self-Portrait (A Chinese Cowboy)》, 2018,fine art inkjet printing

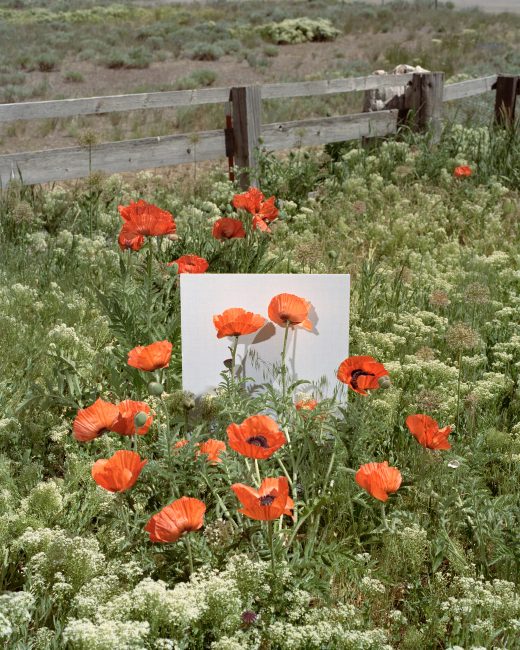

Of the subjects in The Chinese Question, the poppies that Chinese workers brought to the American West seem particularly vivid. The Chinese variant of the plant, a metonym for Chinese opium consumption, also became a negative symbol for China. When Andong first visited Tuscarora, a town to the north of Nevada’s county seat, Elko, the Chinese poppies growing outside of the houses immediately caught his attention. An old man who lived there explained that they had been planted, hundreds of years ago, by Chinese immigrants; because of their incredible vitality and tenacity, they had survived until today. But it was already midsummer, and so the majority of the poppies had withered; Andong could only arrange to come back the beginning of the next summer to shoot. His plan worked out: starting from April of the second year, he and the old man would talk over the phone, and the latter would tell him how the weather was in Nevada, and what time the poppies would flower. What do the two flowers placed in front of gridded, white paper in the photograph stand for, other than material evidence of a bygone history—do they, perhaps, accidentally suggest this incredible yet sincere connection?

Andong Zheng,《The Oriental Poppies in Tuscarora, Nevada》, 2019,fine art inkjet printing

Compared to the bleak, current reality of the US, driving westward and taking photographs along the way seems like an experience so carefree it’s cruel. To complement The Chinese Question, in mid-March of 2020, Andong moved to Flushing, Queens—a well-known Chinese enclave in New York—this also gave him some relief from Manhattan’s expensive rent. To Andong, living in the epicenter of the outbreak made it significantly harder to take photos of strangers; and to compound things, the vastly different lives of his Chinese neighbors swiftly dissolved the historical mists of “Chinese-ness,” instead pointing to the absurd, ineffable quality of living and surviving in the present moment.

“My neighbors each had separate life patterns. The middle-aged guy next door was a car salesman at a nearby Honda dealership; his wife and child were in Taiwan, and he lived alone in the States, sending money home each month. Across the hall were two people close to my age, one of them was a taxi driver, who’d come on a tourist visa two years ago and was now living undocumented, making a living working for Uber and a Chinese van service. He left his apartment each day at five or six and came back very late; he claimed that he could make more than ten thousand dollars a month, and that he’d already used this income to buy two pieces of real estate back China. Another person was an illustration teacher at an education company; during the outbreak, she didn’t leave her room, teaching class remotely every day. She said she wanted very much to stay in the US, but didn’t know whether staying was the best choice. In the attic lived a nurse who worked at a nearby hospital, who slept in the day and worked at night. She had a green card, and didn’t need to worry about being deported. And in the basement, there was a couple, but I only met them a few times by chance, and never got to know them.”

To the numerous international students in predicaments similar to Andong’s, the numerous doubts that revolved around the issue of “Chinese-ness” were roughly interrupted by the looming end of their legal status, skyrocketing flight prices, and the intricacies of returning to China. What once was a process of redefining one’s own identity based on changes in time, geography, and professions, including the changes, intentional or not, to one’s “coordinates,” now became a nostalgic game once played in a less anomalous era; yet when these feelings of indeterminacy had lost their savor, these so-called identity issues lost their urgency—amidst the roil of language and information, only history’s tireless, emotionless repetitions remained; as for the “I”, it seemed that only by thinking about it less and less, could its contours and tones become clear.

Andong Zheng,《A J-1 Visa Summer Work Program Atlendee, Nevada》,2019,fine art inkjet printing

“I felt like I’d escaped, though with a certain despair. Now, I ask myself—in the States, are Chinese people the Other, eternally unable to assimilate?

—Of course they are.”

04

I don’t know what Furen Dai, who has lived in the States for eight years, feels about the word “assimilate.” As a student, artist, and public program organizer, constant travel, residencies and visits have made Furen’s life one of constant flux, yet before the pandemic, these migrations and changes formed a kind of steady lifestyle for her.

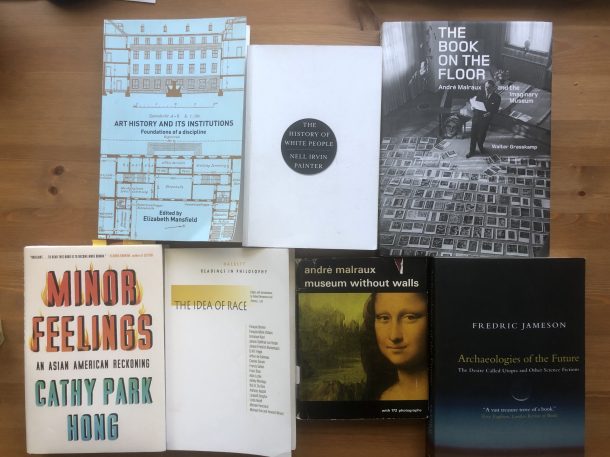

Furen Dai’s reading, during lockdown

Considering the extent of the outbreak in the US, and the myriad resulting restrictions to social contact, Furen decided to temporarily suspend her plan to start a residency at MASS MoCA this November. She told me that all the artists who’d been selected for the residency could still use the studio space provided by the institution, but the cancellation of studio visits and the impossibility of getting together with friends made such a residency lose much of its luster—compared to moving just to work, by herself in a studio, she’d rather jump on the bandwagon and participate in online programs.

Communities are like air. Even though the word, zi-bi, Chinese slang for “shutting oneself in”, seemed to finally be describing the majority of people, long periods of self-isolation and monotonous home lives made people crave fresh air—only when faced with a bed, a table, and a screen all day, did people realize how valuable going outside and seeing friends was, even if everyone just sat and stared at their phones. The excitement of “having lots of free time to do the stuff that I’ve been meaning to do,” lasted less than a month, after which Furen “began to feel a bit down.” It was as though artworks she’d previously done, which invested social issues like marriage markets, culture-driven trips, and linguistic functions, suddenly appeared largely and untimely aesthetic, raising the question for her once again: what kind of social problems could art really solve?

The “VOTE” notice board in front of the Boston Public Library

The solution to, or deferral of, this problem certainly involved social networks that had already been built, but had now totally migrated online. In addition to a few online classes and discussion groups, as well as exchanges with friends in different time zones, Furen’s work with Asia Art Archive (headquartered in New York and Hong Kong) also underwent changes. Because of its connections to China, AAA’s New York staff had already begun working from home in March, when New York was on the cusp of its first major wave of infections. After a few weeks of concentrated discussion and study, Furen and her coworkers began, in June, to recover the public conferences, using them as an opportunity to invite artists and scholars to reflect and discuss COVID-19 and its disruptions to the world. In previous, offline discussions at AAA, Furen had often served as an interpreter; it was obvious how much she missed these real-world interactions. “You know, before an event started at AAA, everyone could read some of our books,” she said. “And we were located a fair distance from the subway, so everyone had the chance to talk to each other on that stretch of road.”

From May onwards, large numbers of Chinese artists and international students chose to return to China, including many of Furen’s friends. The proximity of relatives in Boston, however, helped ease her anxiety about “being the only person who stayed behind.” Meanwhile, workplace discussions of Chinese and Asian art and related topics have swiftly changed to being about a harsh reality: as some Americans began to equate the virus with China itself, one of Furen’s friends launched “Stop DiscriminAsian,” an initiative seeking to resist virus-related discrimination against Asians. In a shared document called “WE ARE NOT COVID,” participants detailed discrimination and violence they or their friends had experienced because of COVID-19; over sixty entries were recorded within mere a month.

Furen Dai, 《Federal Census (Nativity and Mother Tongue)》, 2019, 16 Gauge Vinyl, 82” x 48” and 《Federal Census (Health)》, 16 Gauge Vinyl, fluorescent orange vinyl coated mesh, 64”x 48”

Image Credit: Eli Klein Gallery

On the other hand, her Chinese, Chinese-American and Asian friends expressed totally different perspectives during their discussions—some felt anger and despair about the real, linguistic and physical violence they’d suffered, while others thought more about ways or “strategies” in which their faces, and identities, might be better treated. “But everyone’s struggle was real, so when we talk about solidarity, the hardest thing was to find an issue that could motivate everyone.” When speaking about this, Furen recalled her experience filling in a slip upon reaching US customs, in 2012: “I didn’t think too hard about it. I was Asian, so of course I checked the box for Asian.”

Furen Dai, 《A for America》,2019,installation, wood panels, copper pipe, L brackets, wood screws, vinyl, american flag stamps, paint

Photo Credit:Du Xinchen

Furen’s works, How Was Race Made and A for America might be considered an evolution of this reflexive attitude. These two installations are comprised mainly of text; the former is a collage of the increasingly fine distinctions used to describe race in the US census from 1790 to 2010, on fluorescent textile, demonstrating a detailed, neutral investigative tone. The latter is a more personal analysis of the alphabet, in the context of the continuum of attitudes of America as a great power, describing how the relationship between individual and state and how immigration policy created a nearly insurmountable wall for people who wanted to immigrate. They are like a small bookmark, filled with scholarship and other investigations the artist conducted about her own “grammar” and habitual judgments with regard to “race.” The ingenious strategy deployed in these two artworks seems, today, more like a helpless smile—despite an official value system favoring freedom, equality and diversity, the actions taken by the US government seem more like a cruel, stereotyped classifying system. Similarly, an awkward and anxious retrogression away from globalization these past few years have revealed that individuals in transit are not “balloons,” but “kites”: a person’s place of origin still fuels others’ imagination.

This has forced people to turn their attention more towards internal things, in many ways. To Furen, a longstanding interest in feminism allowed her to feel, more acutely, the interactions between people and interior spaces—everyone used the kitchen, the bathroom and other facilities more than usual, but who, she wondered, used certain parts of this interior space more? Because of the failure of artworks to circulate as before, and the inability of artists to travel outside their own countries, it was only natural for museums that were used to organizing monumental international shows to turn their attention to domestic artists. Currently, Furen and her friends are working to create a community of artists who live in Boston: there, individual creation needn’t become a pressing matter. What will be more important is the exchange of and respect for different positions and perspectives.

Furen Dai,《Who Defines Race?》, 2020, 15”x23”, gouache, color pencil on BFK Rives Printmaking Papers

A bit hard to imagine, but also oddly convincing—thinking through the state of quarantine and isolation ultimately brings us to fewer “selves” and more “others.” In a present moment where each of us is increasingly tired of the myriad disruptions to our ways of life, perhaps it is these relative distances, inexorable and inexplicable, that reveal the state of a world continuously splitting apart, and reforming itself—rather than defining identity, fearing and hating “the other,” and obsessing over finding “a tribe”, I would much rather call the flux in which we all find ourselves a kind of unsettled consciousness.

Special Thanks to Angie Nee,Andong Zheng,and Furen Dai

Translated from Chinese by Henry Zhang

Originally published on LEAP F/W 2020 Issue “lIVING IN BUBBLES”

[1] On the afternoon of January 31, 2020, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services held a press conference at which it was announced that non-citizens and non-green card holders who had visited China within the last 14 days would be denied entry into the United States. The U.S. border will officially enforce the denial of entry for these travelers at 1700 EST on February 2, 2020.