Hauntologies of Chinese Contemporary Art: Instant Retrospectives Redux

| July 2, 2021

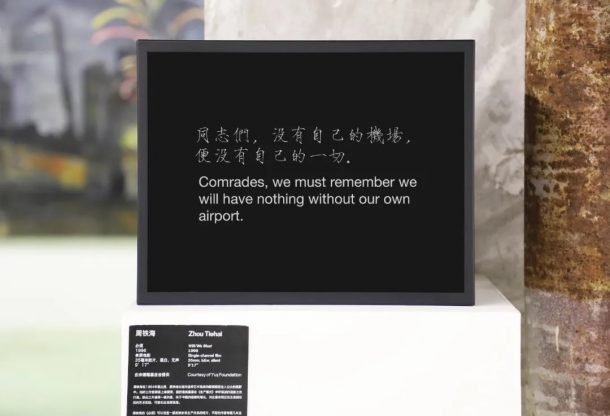

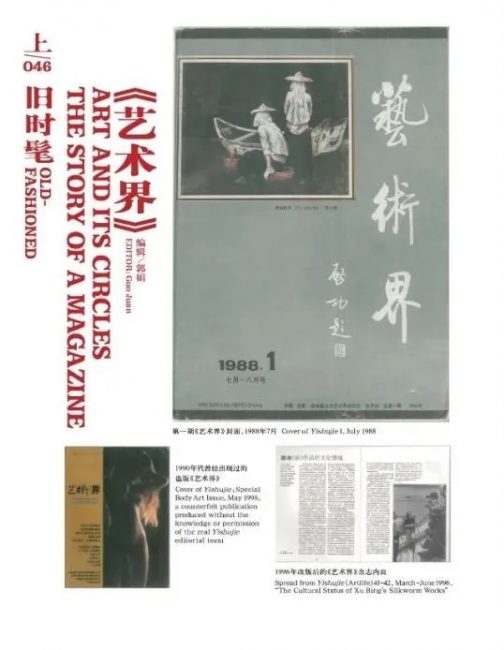

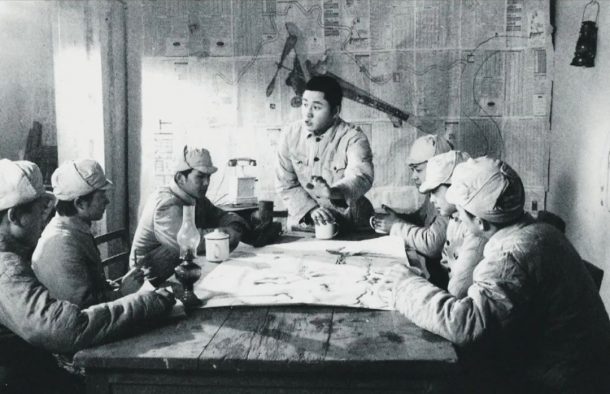

One of my most vivid, easily recalled memories is of reading the inaugural issue of LEAP. This was in 2010, At the time, I was standing on the top floor of the now-defunct Taipei Contemporary Art Center; a friend had lent me the magazine, and told me that it espoused a “native internationalism”: both Chinese and Western. This was a prevailing style at the time—take Beijing’s Arrow Factory, for example: the further into a hutong you walked, the more international things got; the smaller the dimensions of a space, the more influential it was. The magazine’s pages, typeset in both Chinese and English, were redolent of the bilingual Japanese publication ART-iT. In the column “Old-Fashioned,” one discovered that the magazine Yishujie (the Chinese title of LEAP) was actually established during the 1980s. Here was a case of purchasing the license of an old title and summoning the specters of the past, making one realize that the brand new LEAP was actually a reinvention of an earlier magazine. The most cringeworthy yet useful segment was an opening photo shoot in which members of the art world were photographed like celebrities; titled “Airports,” it was a subtle nod to Zhou Tiehai’s satirical silent film Will/We Must (1996), pointing out that China ought to build its own airports, to “welcome museum directors, critics, and gallerists from all countries.”

Zhou Tiehai, Will/We Must, 1996,Installation view

Courtesy ShanghART Gallery and the artist

Especially noteworthy is that in 2010 Chinese contemporary art was still young. LEAP’s inaugural issue ran a cover feature titled “Chinese contemporary art since 2000.” Looking back now, I realize that in today’s Chinese contemporary art landscape, each year there are a few exhibition programs that look back at the history of Chinese contemporary art. I like to call the rapid emergence of so many exhibitions of this kind as “instant retrospectives”: freeze-dried and ready to go. Mostly they invite specters of the past to haunt the contemporary moment. But each time they look back, the efficiency of the transmission decreases. It is as if they seek to bury these artists alive, to nail the lids onto their coffins, and transform them into undead presences. Beijing’s and Shanghai’s instant retrospectives traffic in false nostalgia for past events and objects—very few people really believe in them. But search for their raison d’être, and one realizes that it is the myriad real futures that have vanished. No one can create entirely novel, epoch-marking art any more; even the imagination for such projects has been occluded.

Cover of Yishujie 1, July 1988

Pessimistic Hauntology: “Yesterday’s Music Is Today’s Trend”

Theorists have come up with different attitudes toward the disappearance of the future. Hong Kongese critic Ackbar Abbas uses the speed of Asia’s change as the context for a discussion of Hong Kong’s hauntology. He focuses on the style pioneered by the city’s New Wave film: deliberately nostalgic, yet evincing a kind of temporal dilemma—only when Hong Kong began to worry about the disappearance of its identity did it begin to fashion a unique self-recognition that had never actually existed. This kind of hauntology is stranger even than déjà vu. Abbas describes it as “déjà disparu”: “the feeling that what is new and unique about the situation is always already gone, and we are left holding a handful of clichés, or a cluster of memories of what has never been.”

Applying French philosopher Jacques Derrida’s method of deconstruction to pop music, Mark Fisher’s writing about hauntology represents exactly this kind of resignation: “What it means to be in the 21st century is to have 20th century culture on hi-res screens/ distributed by high-speed Internet, actually.” Fisher gives an example: if you played music from the twenty-first century to listeners in the 1970s, they would be quite surprised—surprised by the music’s inability to deliver a sense of “future shock.” Such music would sound familiar to the point of weirdness—a kind of déjà vu.

In one sense, Fisher writes about such nostalgia from his own sense of disappointment as a music consumer, but he also tries to describe the formation of such “hauntological melancholia” from within: how capitalist realism, bolstered by new communication technologies, has succeeded in capturing our desires. Sometimes, this melancholy about a future that is declared dead before it even begins might appear suspiciously like lamenting the decline of a dominant culture, but Fisher is quick to declare that what he is describing must not descend into a kind of “Left melancholy” over the truth, beauty, and goodness of the erstwhile welfare state, or into a kind of “postcolonial nostalgia” that stubbornly denies global changes and longs for an earlier period of colonial power.

Worth noting is that while Fisher was theorizing hauntology he was also establishing a kind of hauntological writing style. In Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures (2014), he uses the technique of the thought experiment to allow his text to flit in and out of different times, creating various Ballardian “inner spaces” (“If this song from the 2000s had appeared in the 1970s, then…”) This music-review style seems intended to make time “out-of-joint,” as Fisher repeatedly returns to his own formative years, commenting on the technological conditions, culture, and personal and collective spiritual landscapes of the time.

Mark Fisher, Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures, 2014

Zero Books, 245 pages

Ghosts of My Life might be influenced, in part, by Lee Edelman’s explosive polemic, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive (2004). Edelman’s critique is that major elements of the future have already been occupied by mainstream society’s “reproductive futurism.” The most urgent action that queer people can take, then, is to withdraw from such a collective future. In his review of No Future, Fisher points to Edelman’s most incisive question: “What would a theory look like which is not oriented toward a ‘better future’?” As if in response, Fisher borrows from theories of political economy, officially declaring, with a music fan’s disenchanted, melancholic tone: “The dimension of the future has disappeared,” and all that remains is a continuous series of echoes.

In Chinese contemporary art’s “timezone,” avant-garde artists have indeed chosen to bury themselves alive, fleeing future actions. Curator Biljana Ciric once quoted the novelist Lu Huanzhi’s institutional critique to assert that when artists stop making art, art history and the opinions of their peers will “bury them alive”—to stop making art is akin to the artist’s death. Is this not mainstream society’s banal imagination of life? Though it has never been confirmed, there is a strong possibility Lu Huanzhi is the artist Qian Weikang, who left the artworld during the 1990s. His and Ciric’s novelistic and curatorial collaborations are intended to portray anew an artist’s withdrawal from artistic practice on the eve of the work of art’s being “inventoried and sold,” refusing to make art that will one day transform into garbage.

Zhou Tiehai, Will/We Must, 1996,Single-channel film, 35mm film, black and white, no sound,9 min 17 sec

Courtesy ShanghART Gallery and the artist

Optimistic Hauntology: “Yesterday’s Commodity Is Tomorrow’s Found Art Object”

The spectral pessimism referred to here envisages the future as one of decline. However, if one thoroughly thinks through hauntology, one realizes that its argumentative core lies in the fact that just as there is no origin or starting point, that such an origin is always already a carbon copy, neither is there a real end. After a body text comes the appendix, and more. Good retrospectives can also bring to life the dead objects of the past. Often, especially in Asia, the end of something is a highly contingent event. In 2019, Beijing’s Arrow Factory, which had been in operation for 11 years, decided, after only a week’s consideration, to shut its doors for good. Another nonprofit, Manila’s Green Papaya Art Space (2000–21), began long ago to discuss the most appropriate way to cease operations and tidy up its archives; the plan was to properly bid farewell this year—no one expected that in 2020 a fire would rip through the space. But during the Covid-19 lockdown, the staff collaborated with Malaysian curator Yap Sau Bin to organize an online project and dialogue, “Right People, Wrong Timing.” As the coronavirus spread, the project interviewed various independent art collectives that had at one point or another been involved with Green Papaya, and whose dreams had come to nought. Lives that had already ended were bound together in fellowship. The story goes that when Arrow Factory was invited to participate in “Right People, Wrong Timing,” its staff paid tribute to Green Papaya, expressing heartfelt regret at not having encountered the other art space earlier.

Zhao Tao, Zhang Xiuliang, and Zhang Mengmeng / Social Sensibility Research, Badlands, 2016,Installation view at Arrow Factory

Courtesy Arrow Factory

London-based Filipino artist Pio Abad has reproduced a series of ill-gotten art objects from the collection of the Philippines’ former president Ferdinand Marcos and his wife, Imelda, compelling the public to once again look back on this period of history. In the new context of an exhibition, attentive viewers discovered that the collected objects, which spoke for their owners’ onetime private wealth, had suddenly lost their bright, decorative exteriors, and, as if changing expressions, to express a belated apology on behalf of the Marcoses. To the artist, the glaring absence of an apology was the sticking point of this period of history. He began a talk at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco by borrowing Arjun Appadurai’s formulation to explain “the social life of things.” This is the key formula Abad uses to reconstruct the narrative: “Today’s gift is tomorrow’s commodity. Yesterday’s commodity is tomorrow’s found art object.”

Pio Abad and Frances Wadsworth Jones, The Collection of Jane Ryan & William Saunders, 2019

Twenty-four reconstructions of pieces from the Hawaii Collection, modeled from photographs taken by Christie’s

©Pio Abad

In 1986, Appadurai came up with “the social life of things,” a concept meant to end the unique position that the commodity enjoyed in Marxist analysis. He pointed out that any object can become a commodity and, in the process, accumulate value both as a result of human transactions, and independently over time. Consequently, the belief, in modern culture, that only humans have agency ignores the “vital force” of objects is problematic. In 2006, Appadurai wrote “The Thing Itself,” an essay on the development of contemporary art over the previous 30 years, and used it as an occasion to further clarify his formulation. There is an aspect of contradiction: when we talk about “specters,” a certain animacy unconsciously controls our views about life. When the specter of the so-called past haunts the present, his formulation holds that this is merely an auratic value generated by “the social life of things.”

Song Dong, Waste Not, 2005,Installation and event, dimensions variable

View of “Project 90,” MoMA, New York, 2009

Song Dong, the avant-garde artist active in China’s underground art scene during the 1990s, perhaps best embodies the optimistic hauntology of “the social life of things.” In 2007, looking back on his artistic career, he expressed that, due to rapid social change, “In the 40 years of my life I seem to have experienced many different lifetimes.” From 2002 to 2005, Song embarked on his “Waste Not” project, exhibiting objects that his hardworking mother had begun to hoard in 1960 and which had grown to an inventory of more than 10,000 items. Standing in the exhibition space, filled with an enormous volume of everyday things, one could not help but think back to the economic bubble of 2007, contrasting sharply with the monumental artwork-commodities that filled the entirety of the surrounding spaces. In reality, the feeling of déjà vu is not necessarily a case of returning to tired clichés. Song Dong’s original intention had been to relieve some of the pain his mother, who had recently lost her husband, felt when seeing the objects they’d owned together; it turned out, however, that the specter of material privation, which emerged from China’s impoverished past, resulted in this spectacle of fertile excess in the exhibition space. This positive example tells us that in Asia’s rich visual cultures, we might add an aspect of “the social life of things” to Fisher’s hauntology—or if you like, an aspect of Song Dong’s “waste not.” In any case, the point is that “today’s gift is tomorrow’s commodity” and “yesterday’s commodity is tomorrow’s found art object.” Even if buried alive, objects become seeds, waiting for the right time to spring anew from the soil and become valuable once again.

Translated from Chinese by Henry Zhang

- Abbas, Ackbar. (1997) Hong Kong: Culture and the Politics of Disappearance, Minneapolis: Univ Of Minnesota Press;

- Appadurai, Arjun. (2006) “The Thing Itself,” Public Culture 18 (1) Durham: Duke University;

- Fisher, Mark. (2014) Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures, London: Zero Books;

- 陈玺安(2020),“速溶回顾展:快速打包,即刻上新”,《黑齒》杂志。<http://www.heichimagazine.org/zh/articles/2/instant-retrospectives-freeze-dried-ready-to-go>