Peng Zuqiang: Hesitations

| March 24, 2022

Peng Zuqiang, Keep in Touch, 2020-2021, multi-channel video

All pictures courtesy Antenna-Tenna

In the opening scene of the film Revolutionary Road (2008), the protagonist Frank Wheeler, sitting in his car, attempts to wrap an arm around the shoulder of his wife, April, to comfort her over an unsuccessful theater performance. His kind intent, not yet conveyed through physical touch, is the last straw for the distressed April. Bit by bit, their pent-up desires and frustrations fill the “post-performance” void. Eventually they find themselves in a heated argument by the side of the highway. However, between caring—which is shown as a habitual act between the couple in the movie—and the sudden outburst of helplessness, meanness and even hatred, there exists a turning point that cannot be precisely identified. Maybe it is hidden in the endless delay of that intended touch. This moment is specific but hard to pinpoint.

Peng Zuqiang’s recent solo project Hesitations presented by Antenna Space transforms the potential countless facets of such moments into concrete images. The temporary collaborative gallery space hosting this exhibition is located in a townhouse built in the 1920s. In places, the architecture looks dilapidated, as if in a state of unguardedness. The show consists of two works: a sculptural piece, and the five-channel installation Keep in Touch (2021), which consists of moving images shot on Super-8 film and high-resolution recording, installed on the third and fourth floors of the townhouse. In the video, hesitations and reticence interweave with pleasantries and abrupt arguments, resulting in a long-running, uneven but connected emotional continuum.

Peng Zuqiang: Hesitations, installation view, Antenna-Tenna/Objective, Shanghai, 2021

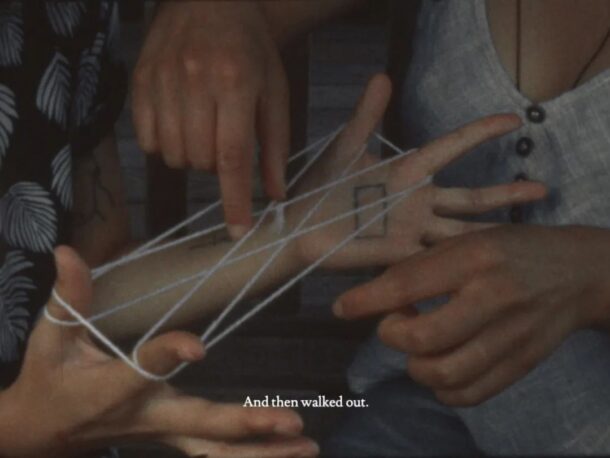

Cat’s cradle is a childhood game that many people are familiar with: after a few rounds, the strings wrapped around one’s fingers have exhausted their possible patterns or get in a tangle all at once due to a player’s mistake. On the third floor, in a room painted purple, a TV displays video footage of a game in progress between two people. Off-camera, a man and woman discuss the fragile balance between “exploring the game’s rules” and “keeping the game going”—their sharp and trenchant words addressing not the cat’s cradle seen onscreen but their experiencing of queer otherness. The absent third party and not-so-smooth communication make for an extraordinarily lively conversation. While a piano melody plays in the background, the video presents the movement of string between the two people’s fingers. It conceals and pulls parts of the two bodies, acutely exposing the hesitation, stupefaction, calculation, and compromise in this game through blank space whenever the two come into physical contact. The movement corresponds to the ebb and flow of the dialogue as well. Together, they complete a compound structure of probing—we cannot be sure if the speakers are the two who are playing the game, but here the cat’s cradle becomes a representation of communication in which intimacies are shared.

Peng Zuqiang: Hesitations, installation view, Antenna-Tenna/Objective, Shanghai, 2021

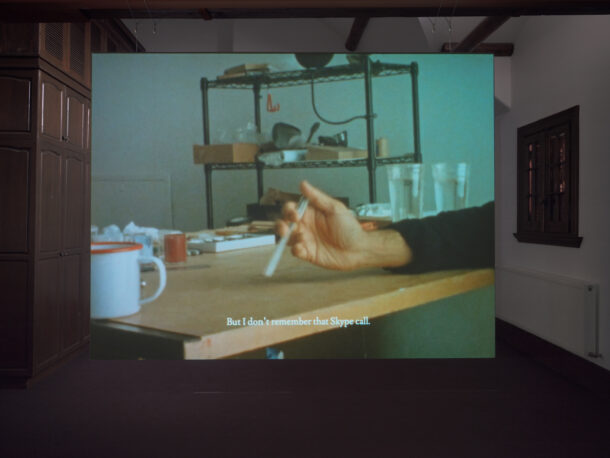

On the fourth floor hangs a double-sided projection screen, which shows footage of two people clipping fingernails for each other on one side and the delivery of a monologue lacking an obvious point on the other. Bodies are only partially shown; verbal expressions are made without any direct link to actions. On one side of the screen, narrative phrases and queries appear as subtitles interspersed among the dynamic nail-clipping actions, their tones wavering between voluntary submission and mild violence. The grainy texture of the film focuses the viewer’s imagination on a curved blade cutting deep into a fingertip. Reacting with an involuntary jerk of the body, the viewer is reminded of the fragile boundary between trust and hurt. On the other side of the screen, the narrator, shown only as limbs and torso, recounts the fragmented memory of an online call. Images of a pen alternately spinning and still in the speaker’s hand draw a direct analogy to a halting communication.

Peng Zuqiang, Keep in Touch, 2020-2021, multi-channel video

The playing of cat’s cradle, the clipping of fingernails, and the spinning of a pen can all be seen as a kind of everyday scribble. As the most ordinary of actions, they serve as common respite in our private lives. However, in Keep in Touch, as the subjects become aware that their forms of communication (conversation, monologue, and subtitle) are dangerous and ineffective among specific groups and untransmittable toward their already diluted objects, the aforementioned actions are used to hide emotions. With an outwardly expanding desire, these actions are the preemptive search for a “more intimate” relationship after the subjects have abandoned straightforward verbal expression. But they are canny and quick-witted too, always ready to get rid of the intentions that sought emotional approach or a strong sense of identity, like a cup of water becoming nonconductive after its minerals have been filtered out.

Akin to our familiarity with the patterns in cat’s cradle, we are too accustomed to using formulated languages. The result is, to one’s surprise, that originally straightforward physical touching and verbal expressions now become secondary to cryptic secretiveness. Instead, the difficulty and unpleasantness in the continuation of touch are hijacked by established linguistic programs, so that people have to keep inventing new signifiers for connections—even when people fail to coexist in a homogenized verbal space due to their cultural and identity barriers, reticence becomes an intense expression as well.

Peng Zuqiang, Keep in Touch, 2020-2021, multi-channel video

The other two clips on the third floor of the townhouse demonstrate the poetic quality and tension of reticence: in a visual parallel to the magnolia trees outside the window, the TV placed on the balcony plays footage of a young girl on a park promenade applying cooling ointment to her wrist, the acupuncture point on her face, the nape of her neck and her ankles. The girl is at ease, hinting at a correlation being formed between the way she touches herself and her spiritual world. Meanwhile, the noise of an automobile engine coming from another room sounds like a small war being waged. But really it is two men, one seemingly Asian and the other Black, standing silently on opposite sides of a car parked in a vibrant green forest. From time to time they scrutinize each other. This is one of the few moments in the video when the audience can fully see the faces of the protagonists. If viewers watch with close attention, they might see subtle provocation and suppression in the two men’s facial expressions, but they remain tight-lipped throughout the video. Renowned film Happy Together (Wong Kar-wai, 1997) set the scene for this kind of cinematic articulation, so it is likely some in the audience had that film in mind while speculating on the elusive context of this confrontation. Although there is no obvious emotional turmoil in the video, the missing closure and abrupt ending prove that reticence can nonetheless be noisy and intense.

Peng Zuqiang: Hesitations, installation view, Antenna-Tenna/Objective, Shanghai, 2021

If one looks closely at the resin handrails hanging vertically at the staircase, they will find faintly engraved on the inside a line that reads, “pointing back to ourselves.” Like a footnote, this tiny installation alludes to the fact that all emotional movements induced by touching eventually return to oneself. In those dispersions that happen sporadically, the emotional frustration evoked by touching and evading brings about a massive margin that exists beyond all forms of verbal expression. This small margin, which holds sensitivity and defiance, and links reticence with ambiguity, points to the bare minimum of freedom we should be pursuing.

Peng Zuqiang, Untitled (grip), 2021, resin, silkscreen print on transparency film, 16 x 17 x 2 cm

But I do not believe that anyone who has experienced such freedom can resist its tenderness and delicacy. When we are immersed in this microclimate consisting of narrative passages, when we bury our heads unconsciously in the perusal of scenarios, we can temporarily forget about things that happened externally which have a straight and clear-defined preference. Undoubtedly, these moments that have yet to be defined collide and grind against each other, in an effort to approach the essential core of the complexity and fragility of connection. But at the same time they also avoid any further advance toward determined emotions, so as to cancel any absolute argument or estrangement—the latter is the emotional state that never fades away in reality. To some extent, the exhibition itself is stationed in a certain manner that positions itself between opening up to the audience and looking inward. But here the instant validation and self-transition of an emotional movement would still return to the rough reality—it cannot tolerate our exploration of alternative communications as we please. Therefore, a world constructed by ambiguous moments cannot remain forever intimate and safe, as we naively wish. Excessive ministering to the sentiment of “nothing happened just now” tends to understate the real dilemma as a haze of tender feelings.

To propose a practical question: when the calibrated verbal expressions still assume their roles as the predominant majority to reinforce themselves, how shall we interpret the sense of touching and its absence? How shall we turn the “unnamed” into the “unignorable” so that we can gradually overturn the politics of measurement? Or shall we say, these nebulous forms of tension-filled reticence still remain the most common solutions at this moment?

Ren Yue

Translated by Lily Sun