Diriyah Biennale: Feeling the Stones

| November 1, 2022

The title of the first Diriyah Biennale derives from a phrase—“Crossing the river by touching the stones”—coined in 1950 by Chen Yun, later the second chairman of the Central Advisory Commission of the Chinese Communist Party. Chen deployed it to argue for a slow, steady approach to government, and during the 1980s the phrase became closely associated with Deng Xiaoping’s “reform and opening up” economic policies. Saudi Arabia was one of the last Middle Eastern countries to recognize the Chinese Communist Party as the government of China (in 1990). This biennale then, with director and chief executive of China’s UCCA, Philip Tinari, at the helm, marks how much things have changed. Although, naturally, it also suggests that you can never escape the feeling that international politics have a role to play in the underlying framework of the show.

The exterior of Diriyah Biennale Foundation

Courtesy Canvas

The biennale takes place in a vast warehouse-like complex (occupying a whopping 12,000 square meters in six connected buildings) located in a suburb of the capital city, Riyadh, and seeks to be a launchpad for the conversion of this industrial district into a culture factory —— a site for year-round exhibitions, workshops, and other interactions, both on a global and local scale. This is not to say that the Diriyah Biennale is any more or less instrumentalized than any other similar-sized art event, just that it wears its instrumentalization on its sleeve (the view from some of the windows in the biennale offers up a wasteland of construction rubble). I’m not a total cynic, but you do need to walk into these things with your eyes open.

It’s change and coping with it that form the exhibition’s core themes. More specifically, the biennale, while comprising work by 60-plus artists from around the world, is a comparison between China, and the emergence of its contemporary art scene during the reform period of the 1980s, and the government-backed contemporary art scene of Saudi Arabia, now emerging from relative isolation—the Land art festival Desert X is in its second edition, the Bienal Sur (which focuses on art from the global south) took place in Jeddah in 2021, and an upcoming Biennale of Islamic Art is due in the same city. As the biennale handbook puts it, somewhat glossing over the separations in geography, chronology, and political systems (Saudi is a kingdom), these two scenes share “a similar moment of optimistic energy,”, while “in moments of great change, art plays a central role, exposing viewers to novel concepts, empowering individuals to imagine new ways of being, and providing a space to think through and discuss critical ideas.” Naturally the 2018 murder of Jamal Khashoggi at the hands of government agents at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul remains something of a looming counterpoint to that. An elephant, albeit in a very large room.

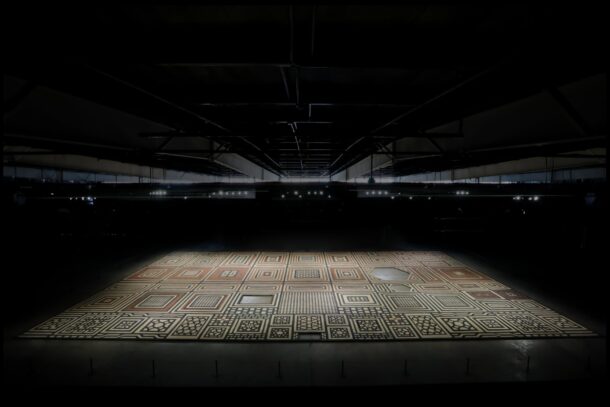

Dana Awartani, Standing on the Ruins of Aleppo, 2021, installation

Courtesy Canvas and Diriyah Biennale Foundation

Given the scale of that room, it’s no surprise that the biennale houses a number of large installations, and one of the standouts among them is Saudi-based Dana Awartani’s Standing by the Ruins of Aleppo (2021), a fullscale (20 meters long and 10 meters wide) replica of the geometric patterns of the courtyard of the Grand Mosque of Aleppo, an eleventh-century structure that was destroyed in 2013 during the civil war in Syria. The new version is made up of thousands of adobe bricks and clay earth (which come from various locations across Saudi, to offer a secondary reading as a ‘real-life’ map of the kingdom), which, lacking any binding agents, consequently deteriorate during the course of the exhibition. Yet, while it alludes to a moment of cultural destruction and the notion that, contra the exhibition’s general positioning, change is not always good, this is a welcome complexification of the theme. A different kind of nostalgia is present in Saudi artist Maha Mullah’s Food For Thought series (2020), which in the commissioned incarnation here takes the form of 3,840 cassette tapes (featuring religious readings from the 1980s) racked into bread trays and attached to a wall in such a way that they form another map, this one a pixelated map of the world, and spell out a series of Arabic letters (prominent among them an ‘ayn, which sounds like a sigh, and presumably references the COVID-19 pandemic and the way in which it has accelerated global connectivity at the same time as it has reduced more localized interactions). At once an archive and a monument, both to technology’s power to connect communities (the tapes would once have been played at intimate social gatherings; the map might suggest communication on a less personal scale) and its inbuilt redundancies, the work continues to establish change as the product of dialectics rather than teleology. Indeed, it’s a feature of many of the works on show here, that modernization and progress are accompanied by a certain amount of disquiet as much as celebration.

It’s a theme that’s picked up again, for example, in Egyptian painter Ibrahim El Dessouki’s pentaptych Series of Gated Communities (2020), which documents the isolation, lack of context, and superficiality engendered by ‘modernized’, gated -living developments in his home country. And in Zhang Peili’s Broadcast at the Same Time (1999.12.31) (2000), which comprises 26 CRT televisions screening recordings of various news broadcasts from around the world at the end of the last millennium, placed in a circle and offering viewers a cacophonous and disjointed vision or what was worrying the world at the time and how those stories were spun. But while it may have been revolutionary in its examination of the increasingly globaliszed world at the time, it now seems like a commentary on what we already know. Indeed, by the time you get, in the latter stages of the show, to Lawrence Lek’s Nøtel (Red Sea Edition) (2018/2021)—a speculative ‘hotel’ for global nomads explored via video-game technology—and John Gerrard’s LED wall featuring a dancing human tree (rooted—ha, ha—in European traditions of the Green Man) in Leaf Work (Derrigimlagh) (2021), you feel more uncomfortably connected to our presently abstracted world and its concerns. And Zhang’s work inevitably feels more like a historical artefact. Which perhaps it always was.

Maha Malluh, Food for Thought “WHORLD MAP”, 2021, installation

Courtesy Canvas and Diriyah Biennale Foundation

Lei Lei and Chai Mi’s 1993–1994 (2021), is a two-channel video installation that features footage shot by Chai’s father, while he was working in the Gulf for a seven-year period during the 1990s. It explores the relationship between a migrant worker and a strange and alien land, the maintenance of connections to the place you came from, and the life and relationships you left behind. It’s more personal and intimate than many of the other works on show, which go for statements on a grander scale. Perhaps, indeed, for those reasons, it’s the key work in the entire show. And one that has a continuing relevance to the migrant -labor forces that fuel the Gulf (alongside oil) to this day. It’’s also a work that finds echoes in Koki Tanaka’s Abstracted/Family (2020), part of an excellent and no-less-moving ongoing project. In this version, the Japanese artist asks four unrelated native Japanese speakers (either born in Japan or immigrated to the country at a young age) whose family background is visibly from elsewhere, to role-play as a family in an exercise that speaks to both ideas of belonging and the relevance of inherited cultural baggage.

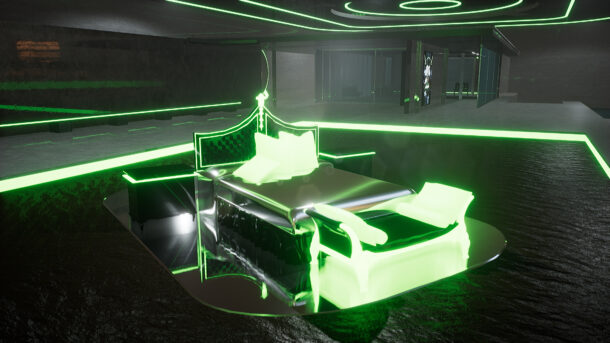

Lawrence Lek, Netel (18 Third Suite Enjoy Your Stay), 2016—ongoing, multimedia installation,VR experience, open-world game, variable duration

Courtesy the artist and Diriyah Biennale Foundation

If most of this makes the biennale seem coherent, connected, and filled with echoes, it is and it isn’t. Every time it gets going, it drifts off somewhere else, leaving the connections to occur in later synaptic firings. Of course, this in itself might not be a bad thing,; as Awartani’s work reminds us, things often come together only to remind us of how they can fall apart. But it’s a sensation not helped by the seemingly random insertion of micro-exhibitions by the Nairobi Contemporary Art Institute, a collection of works on canvas dating from the 2000’s from Jeddah’s Al -Mansouria Foundation, and a bizarre architecture section, featuring, among other things, Italian group Superstudio’s drawings from their Endless City project, dreamt up at the end of the 1960s as a “negative utopia” and a warning against the onward march of urbanization. At the beginning of 2021, Saudi Arabia’s crown prince announced plans for a 100-mile city dubbed “The Line”, which architecture critics such as The Guardian’s Oliver Wainwright immediately linked to the earlier Superstudio project. It leaves any visitor to the Diriyah Biennale unclear as to whether what was originally a critique has now been turned into an advertisement. But perhaps that’s the true function of any biennale these days.

Lei Lei and Chai Mi, 1993—1994,2021,two-screen video

Courtesy Canvas and Diriyah Biennale Foundation

Mark Rappolt