Protect or Expose? Decoloniality in Times of Strife

| July 25, 2023

“The twentieth century prematurely ended in the late 1980s, while history continues.” [1]

In the late twentieth century, following the mass withdrawal of the last European colonizers from Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean, the forceful control and plundering of colonialism came to a near end. Since then, decolonization has emerged as a core value, concept, and method in the art world. In terms of tangible reality, western art institutions have been showing nonwestern artists and works extensively, from the 1989 exhibition “Magiciens de la Terre,” at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, to the research, exploration, and presentation of diverse forms of localized modernity by institutions of all scales today. Yet the postwar order remains largely European-American in its rationale and thrives on resources, labor, and profits plundered from developing countries through both economic and cultural neocolonial means. In direct reference to structural privilege and prejudice in art institutions, decolonization discourses continues to interrogate European-American-centrism and introduce more pluralist issues of race, ethnicity, gender, and class. In the context of the postwar order, however, “pluralism” is not a completely decentralized heterogeneity but rather, still, a “diversity” regulated by a Euro-American outlook. This has resulted in decolonization’s further direct confrontation with the postwar order on intellectual, mental, and ideological levels. Though such confrontation does not yet appear to have resulted in a new wave of placing non-western works in western museums, it is likely to be both extremely constructive and destructive.

In light of the current dilemmas, conflicts, and crises, it seems as though we are moving away from supposedly post-World War II art towards (and may even have arrived at) a “pre-World War III art.” Now, I am not advocating for war or assuming its inevitability, since contemporary wars can take place in diplomatic, economic, and cultural contexts and even in virtual space and time, obviating the traditional battlefield of close engagement; nor am I reiterating clichéd conclusions such as “contemporary art is dead,” because, as the title suggests, even if contemporary art comes to an end, art continues to exist. From my observation of the controversies at this year’s edition of documenta in Kassel to my personal experience in teaching, it seems as if the postwar order that once promised stability, prosperity, and pluralism to the world is now experiencing a total collapse on all levels: political, economic, cultural, religious, and ethical.

From “Platform” to “Rice Barn”

In 2002, documenta welcomed the first non-European art director in its history, Okwui Enwezor. His elaborate curating for documenta spanned five platforms across Asia, Africa, Europe, and the Caribbean, attempting to remove the homogeneous geographical nature of Kassel and to examine systems of knowledge production and decolonization discourses in a global context. [2] In 2002, documenta welcomed the first non-European art director in its history, Okwui Enwezor. His elaborate curation for documenta spanned five platforms across Asia, Africa, Europe and the Caribbean, attempting to remove the homogeneous geographical nature of Kassel and to examine systems of knowledge production and decolonization discourses in a global context. This year’s edition of documenta introduced its first Asian artistic director, ruangrupa, an art collective from Jakarta, Indonesia. The curating of this edition of documenta is based upon the concept of lumbung, meaning “rice barn” in Indonesian, which refers to the sustainable harvest method of collectively sharing among villagers. After gathering the harvest, instead of bringing it home, the villagers store it in the rice barn, which is open to the community and can be accessed on demand. This Southeast Asian emphasis on voluntary, consensual, and collective values clearly contradicts the western order that focuses on profit, efficiency, and the individual. Based on the concept of the lumbung, ruangrupa further decentralized the role of the artistic director by inviting 14 other groups to co-organize this edition. These groups, known as the “lumbung inter-lokal,” invited other groups and artists to participate, ultimately including thousands of artists in the roster in more than 30 spaces throughout the city of Kassel. Ruangrupa encourages the viewer to enter the exhibition by nongkrong—the Indonesian word for aimless casual conversation and hanging out, to “make friends, not art”, and to “learn together.” [3] In doing so, lumbung deemphasizes contemporary art as defined by institutions and markets, shifting the focus of the exhibition to a restless collective of improvisations, talks, workshops, gatherings, and parties… Drawing on Boris Groys’s discussion of the exchange of values between cultural archives and the secular world in “On the New” (1992), Pan Lü vividly summarized the ambiance of this year’s edition as “The living are partying in the graveyard,” and went on to elaborate: lumbung introduced soil (localization) from all over the world to Kassel but did not necessarily connect with the “soil” in Kassel. [4] This explains, in part, the core conflict of the exhibition: the extent of and responsibility for the antisemitism present in works presented at documenta.

Taring Padi, The Flame of Solidarity: First they came for them, then they came for us, 2022, Documenta fifteen, installation view, Hallenbad Ost, Kassel, 2022

Photo by Frank Sperling

Someone as wise and generous as Enwezor was still perturbed by Munich’s social and bureaucratic climate when he was living and working there: “As an African in a mostly monocultural city, I’m one to stand out. And then you ask yourself: Can you feel safe? Who will help you if something happens to you?” [5] Around 2001, Hito Steyerl was invited to submit work to documenta 11, which was curated by Enwezor. Steyerl had previously submitted a short video titled Babenhausen (1997), documenting a demonstration against a series of attacks on a Jewish family, the Merins, in the small town of Babenhausen in Hessen, Germany. The curatorial team ultimately said nothing at all about this work. In that edition of documenta, which examined systems of knowledge production and decolonization discourses, Germany was absent, with very few works exploring issues of racism and immigration in Germany. [6]It is worth considering this context when looking at the controversies of documenta 15, where People’s Justice, created in 2002 by the Indonesian art collective Taring Padi, along with other works and events, were identified as containing problematic symbolism and other imagery, resulting in the labeling of the artists, ruangrupa, and even documenta as antisemitic.

Clay workshops by Jatiwangi Art Factory on Documenta fifteen, 2022

Photo by Frank Sperling

Courtesy Documenta fifteen

The “localization” of Kassel clearly involves a kind of German exceptionalism: the relatively abstract globalization issues such as “Black Quantum Futurism” are used in lieu of a concrete and personal examination of Germany’s past and present.[7] Germany seems to be a place of neutrality, but in fact it also inherited a privilege that nurtures and perpetuates exceptionalism based on postwar political, economic, cultural, religious, and ethical order in all dimensions. Without distinguishing antisemitism in Germany and Europe from the rest of the world, without separating antisemitism from the rejection of Israeli hegemony, the opposition to antisemitism in documenta risks labeling and instrumentalizing antisemitism in defense of Eurocentrism and white supremacy in Europe. [8]The transnational, intercultural curating, works, and writing of Enwezor, Steyerl, and ruangrupa should not be reduced to “antisemitism,” “naïveté,” or “political reparations,” but rather regarded as an ultimate revelation in the ongoing intellectual, mental, and ideological confrontation: Germany is not alone in attempting to claim the privilege of exceptionalism in the name of order.

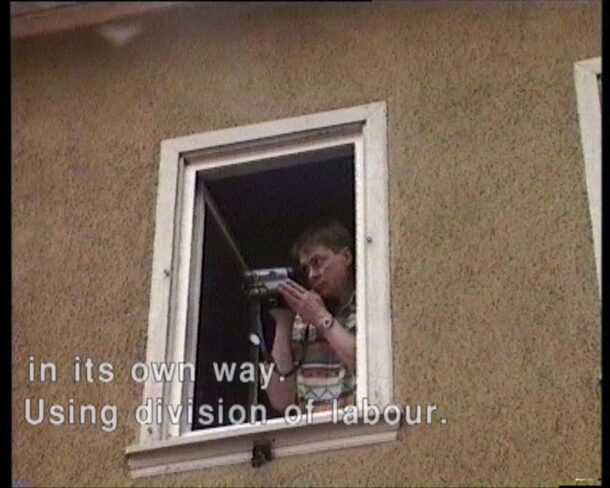

Hito Steyerl, Babenhausen (film still), 1997, documentary, 4 minutes

“We Have to Protect Each Other’s Feelings”

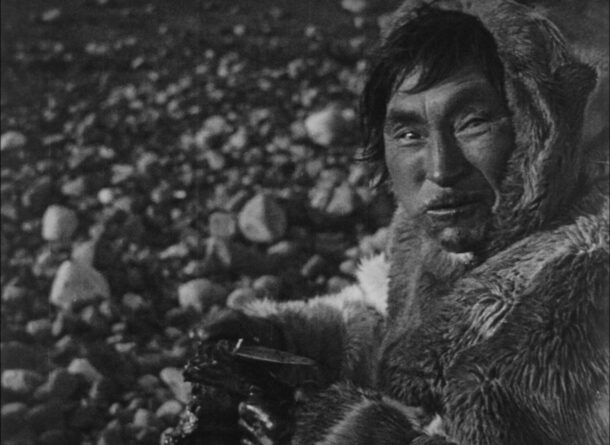

In American art schools it is not uncommon for decolonization to be added to the teaching curricula. [9]Schools are offering many courses on nonwestern art, while professors are introducing nonwestern art into their syllabi. The majority of college students today are the so-called Gen Z, the most demographically diverse generation. I used to teach a course called Art, Mobility, and Ethnography at the University of Cincinnati College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning in the Midwest. In my daily interactions, a distinguished white painting professor once expressed confusion about my stated research focus of visual ethnography: why am I teaching in an art school rather than the anthropology department? Indeed, the construction of nonwestern art history has relied heavily on the ethnographic method, a process of knowledge production that, in recent years, has offered a means of reflection on decolonization issues such as new/old, self/other, and here/there. For example, ethnographic cinema is narrowly defined as a method between film and anthropology, with a specific target audience (usually scholars and anthropologists), that aims to “making a detailed description and analysis of human behavior based on a long-term study on the spot” and “relates specific observed behavior to cultural norms.”[10] In a broader sense, classic ethnographic films, as exemplified by Nanook of the North (1992), address different races, environments, and cultures through explanatory narration and subtitles.

Robert J. Flaherty, Nanook of the North (film still), 1922, documentary, 79 minutes

One issue is that this method of research and representation has also been commodified in western societies where predominantly white audiences watch the “other” as a recreational pastime. I showed a film called Forest of Bliss (1986) during a course. In contrast to classic ethnographic films, the director, Robert Gardner, refused to provide any explanatory subtitles or voiceover, instead allowing the audience to follow the lens and experience the Hindu holy city of Benares on the banks of the Ganges. Showing this film led to a hiccup that was utterly out of my expectation: a student suggested that trigger warnings should be provided before playing the film. This was a baffling request to me; why would an ethnographic film, essentially unrelated to trauma, need to have a trigger warning?

Robert J. Flaherty, Nanook of the North (film still), 1922, documentary, 79 minutes

Robert Gardner, Forest of Bliss (film still), 1986, documentary, 90 minutes

Through exchanges inside and outside the classroom, I roughly understood some of the reasons behind this request: one, the film depicts Hindu daily routines and rituals, not Christianity; two, because it was close to Halloween, some felt uncomfortable with the content of funeral rituals; and three, there are scenes in the film where stray dogs fight for food among themselves on the street. Some of these reasons are so absurd, like the one about stray dogs, and some seem valid enough, such as the different contexts of Hindu funeral rituals versus Halloween, a western festival. The instructor can indeed respond to these discrepancies by offering more background information.

Again, I wonder why Gardner rejected this approach. Like the request for ruangrupa to “provide more curatorial elaboration on the context of the work,” does that mean the curators have assumed the viewers only receive passive input? Does it mean the viewers will not, cannot, do not, or choose not to understand complex contexts actively? There are also extremely disturbing reasons, for example, based on Christian centrism, for placing trigger warnings on films that show non-Christian content or even to regard them as “horrific,” “traumatic,” or “devious.” I then asked my students: How would the film be watched differently if trigger warnings were in place? Their responses were to “block their eyes with their hands” or to “shift focus and avoid watching some of the clips.”

In the end, the students rationalized their behavior with a truth that seemed universal: “We have to protect each other’s feelings.” The truth is that everyone is attempting to plot for themselves the privilege of exceptionalism on all levels of political, economic, cultural, religious, and ethical order: I have the power, or privilege, to cover my eyes to avoid seeing Benares’s stray dogs, to not learn about Hinduism, to not know about the construction of ethnographic knowledge because my feelings need to be protected. In class, I made it clear to my students that I would not use trigger warnings, but as a young teacher, I was not sure I had explained to my students the complexity of the multiple aspects of this issue. Once self-reflection is discarded, “we need to protect each other’s feelings” may seem like a way to “protect diversity,” yet it is essentially the delicate, fragile privilege of exceptionalism to which decolonization is confronting. What is wrong with watching?

The Future of Uncertainty and Certainty

While documenta is a particular center of contemporary art, the University of Cincinnati is a public university in an industrial city situated on the American Rust Belt, peripheral to contemporary art. Although I cannot fully empathize with ruangrupa and the many artists at this year’s edition, when considered in terms of my personal experiences and reflections in academic institutions, the direct confrontation between decolonization and order on the intellectual, mental, and ideological levels is intense, concrete, and subtle. The two are not just a superficial situation of majority and minority but a dialectical contradiction that interconnects, interpenetrates, and excludes and struggles with each other, thereby prompting the motion and change of things. When we discuss the opposition to antisemitism in Germany, what is Germany in this context? Is it all Germans or is it the nation-state? When decolonization refers to the privilege of exceptionalism within each individual, the post-WWII order, which once delivered stability, prosperity, and pluralism, faces a fundamental disintegration on all levels: political, economic, cultural, artistic, and religious, progressing to the “pre-World War III art” that is both highly destructive and constructive. A new order will follow, though with much uncertainty; no theory predicts the new order, but what is certain is that decolonization will always be a process, an ongoing scrutiny, and that history continues from there.

[1] Wang, Hui. (2008) The Historical Roots of China’s “Neoliberalism”: Revisiting the State of Thought and Modernity in Contemporary Mainland China. Depoliticized Politics: The short end of the 20th century life with the nineties (Chinese Edition) (pp. 98). 90 SDX Joint Publishing.

[2] The five platforms of documenta in 2022 in Kassel are: Platform1, Democracy Unrealized (Vienna and Berlin); Platform2, Experiments with Truth: Transitional Justice and the Processes of Truth and Reconciliation (New Delhi); Platform3, Créolité and Creolization (Saint Lucia); Platform4, Under Siege: Four African Cities—Freetown, Johannesburg, Kinshasa, Lagos (Lagos); Platform5, Exhibition (Kassel). See Yu Kefei, “A Study of Documenta 11 in Kassel,” Master’s thesis, Central Academy of Fine Arts, 2016.

[3] Technically, there is a considerable amount of criticism that raises issues with this approach to the exhibition, such as the extremely high demands this engagement challenges on the viewer’s knowledge base, the effectiveness on the posters and mind maps all over Kassel, etc.

[4] “Rolling Congee 20: A true international exhibition is one that creates controversies—A discussion of documenta in Kassel” (podcast).

[5] Steyerl, Hito. (2022, August 5). “Context is king, except the German one.” ArtChina. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/9HHwgvbxTyPCSJel4hfp2w

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] For a discussion of the relationship between opposition to anti-Semitism, Eurocentrism, and white supremacy in Europe as presented in this edition of documenta, see Ren Hai. Perpetual Aesthetics, Historical Institutions, and the Futurism of Planethood: Reflections from documenta 15. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/M_EJtjCsYOHFs6QQy3V4Aw

[9] Gopal, Priyamvada. (2021, May 28). “On Decolonisation and the University” (Aseem, Trans.). Peng Pai. https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_13430130

[10] Heider K. Ethnographic Film. Austin[M]. TX: University of Texas Press, 2006: 5.

Yuxiang Dong is an artist and a lecturer in new media art at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. He was a recipient of the Joint Second Prize in the 5th International Awards for Art Criticism.

Translated by Chloe Yang