Slime in Loops

| March 11, 2024

“Monsters are our children; they may be cast to the farthest margins of geography and discourse, banished to the fringes of our world and the recesses forbidden within our minds, but inevitably, they return.” [1]

-Jeffery Jeremy Cohen

Title page of H. P. Lovecraft’s “The Call of Cthulhu” as it appeared in Weird Tales, February 1928

Open source

In recent years, a slimy substance has emerged as a symbol in numerous artworks, and its symbolic significance has been repeatedly mentioned within the realm of contemporary cultural discourse. Regarding this, it is impossible to overlook its pervasive presence in horror and science fiction literature and film throughout the twentieth century. One of the most well-known examples is the enigmatic entity known as Cthulhu, hidden in the realm of the unknown, which has always captivated people’s imagination. It first appeared in H.P. Lovecraft’s short story “The Call of Cthulhu,” published in the magazine Weird Tales in 1928.[2] However, if we trace back even earlier, we can find its presence in the decaying landscapes of Gothic literature. In Mary Shelley’s seminal opus, Frankenstein (1818), the creature emerges, its “watery eyes” tainted with an almost putrid obscurity. It is a black box suspended betwixt the tenuous realms of life and death, forever poised upon the precipice of existence. Within this liminal state, we glimpse the anxieties concerning the unrelenting leaps of technology.[3] The viscous seems to always be associated with monsters. In the mid to late 20th century, with the outbreak of the first nuclear tests and the growing curiosity about extraterrestrial civilizations, they became increasingly commonplace in films and novels. In the 1958 film The Blob, for example, a towering entity composed of slime devours everything in its path, posing a tangible threat to human society. John Halkin’s novel Slime, published in 1984, depicts a group of gelatinous organisms originating from the deep sea, intensely craving human flesh. The Alien series, spanning nearly four decades, successfully evokes the audience’s strange and primal fear towards the main character, the Xenomorph, through the imagery of mucous substances.

The formless, slimy substance is a powerful symbol. It oozes and lubricates, leaving behind traces of deformation and eerie sensations. The corporeal vessel relinquishes its very essence and succumbs to a state of slimy decomposition, transcending all delineations of form and shape. It intricately mirrors our profound apprehension as we slip from the structured realm of order to the disorienting labyrinth of chaos. As things are always drawn to the process of becoming chaos, the monstrous slime, pushed to the peripheries and the forbidden, always returns to us. The idea of humans manipulating the world as the subject is disturbed and deformed, while the repressed terrifying objects awaken and resurface infinitely in loops in our cultural imaginations as a way to connect with us.

Loop I

A pink sludge upon the plinth pulsates, emitting growling noises reminiscent of an unknown living organism. It is named SONŌ, a soft robot created by Mads Bering Christiansen and Jonas Jørgensen, enlivened with an amalgamation of soundtracks drawn from the monsters that appeared in horror movies of the mid to late 20th century. Crafted with a unique silicone fabric often used in Hollywood’s special effects, SONŌ appears as soft as a living body. Its form echoes the slimy, undulating entities that haunted the silver screen. While the artists seek to explore the essence of life or, in other words, activism through this uncanny “creature” and its soundscape, SONŌ presents an interpermeating relationship between the subject and the object in a ceaseless loop. Similar to the aforementioned monsters, SONŌ is both familiar and enigmatic to the audience, as Julia Kristeva has already perceived in her renowned book, Powers of Horror, which illuminates the idea of the abject—an entity expelled from the realm of the symbolic order, capable of inciting terror and repulsion within individuals.[4] SONŌ is the abject created by the artists to explore the boundaries between the self and the other. It exists beyond the self, yet remains inextricably linked, forever hovering within the realm of the transitional. Herein lies the robot, taking the shape of a tangible residue of biological breakdown—a waste product straddling the tenuous line between existence and demise, bridging the realms of organic and inorganic, animate and inanimate entities.

Even though we often observe these filthy entities as the abject from a safe distance, with a smooth interface in front of us, it is worth being aware that monsters not only connect with us on a representational level but also reside within us biologically.

Jenna Sutela, nimiia cétiï, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Somewhere House (London)

In the video work titled nimiia cétiï (2018), artist Jenna Sutela sheds light on a bacterium—Bacillus subtilis, a slimy bacterial coating that resides in the pipes of dark, dank corners of cities and in our gastrointestinal tracts, as it even traverses to Mars in a science research program. Machine learning is employed to interpret messages originating from the movements of the bacterium Bacillus subtilis and to generate a new written and spoken language based on a Martian tongue from the late 1800s, originally communicated through the French medium Hélène Smith, who claimed to have been spirited during a trance to Mars and thereafter learned their language. In an interview, Sutela explained that humans were never purely human to begin with, as our bodies harbor a significant number of bacteria. The alien is within us and may influence our thoughts and emotions through the gut-brain connection.[5]

Mucus and gel-like materials do, in fact, play a crucial role in the human gut microbiome. They act as protective barriers between the host and the microbial inhabitants of the gut, preventing harmful bacteria from infiltrating the host’s tissues. Simultaneously, the mucus layer promotes the growth of beneficial bacteria that aid in digestion and other physiological processes.[6] The mucus layer and the microbial community it supports are integral to the functioning of humans as holobionts—a concept that views humans as ecosystems comprising both human and microbial cells.

Maybe the very existence of slime in our bodies is the reason why slime holds a primal allure deeply inherent within us, capturing our attention and imaginations. In the 1860s, Thomas Huxley claimed to have discovered the primordial substance protoplasm in the slimy sediment of seabed. It was believed by 19th-century scientists that protoplasm, the complex and gelatinous substance within cells, was necessary for life and served as both the material foundation and origin of life itself. This discovery was viewed as a perfect confirmation of the theory of evolution at that time, suggesting that organisms were not mere manifestations of the characteristics of life, but rather dynamic perpetual processes that transcended time and space. The primordial ooze was deemed as the origin of the processes that could be traced back to an existence between life and nonlife. Huxley’s theory was eventually regarded as a beautiful misunderstanding, becoming suspended in history. However, scientists’ imagination of protoplasm extends beyond regarding it as mere foundational matter; instead, they perceive it as a dynamic medium that pulsates with the energy of waves and the flow of biological material. The gelatinous substance is sensitive, contractile, and capable of movement in waves, leading scientists to draw parallels between protoplasm and other mediums that transmit waves, such as the ether. The observation of protoplasmic behavior, resembling the propagation of waves, suggested that it could serve as a medium for both energy waves and the movement of biological material within living organisms. As philosopher Ben Woodard points out, protoplasm is more like an “epistemic object,” an experimental site that connects both energetic and biological processes, and to a certain extent lays the groundwork for dismantling the reductive binary between materialism and mechanism that enriches and reshapes the discourse surrounding aesthetics.[7]

Huxley named the protoplasm he discovered as Bathybius Haeckelii in tribute to Ernst Haeckel, the pioneering biologist of protoplasm theory.

Loop II

Slime substances, such as biofilms or collections of microorganisms, can be found in almost every habitat on Earth. These slimy communities are essential to many ecological processes, such as nutrient cycling, waste breakdown, and disease prevention. Marine biologist Daniel Pauly speaks of the possibility of an “Era of Slime” – or Myxocene – wherein slime-dominated oceans encompass countless plankton. As Susanne Wedlich, the author of Slime: A Natural History, notes, “this is a man-made catastrophe.”[8] Climate change is altering the conditions in which these communities can thrive, leading to changes in their role in the ecosystem in an invisible way. Myxocene is merely an alternative to designations like Anthropocene, Chthulucene, Plantationocene, among others, but the amorphous essence and remarkable adaptability of slime make it both a powerful nurturing source of vitality and a potential harbinger of doom that is ubiquitous. The genesis that nurtures is also an ending that engulfs everything in its path. Palaeontologist Peter Ward, in his book The Medea Hypothesis: Is Life on Earth Ultimately Self-Destructive?, draws a parallel between this kind of Möbius-like process and the ancient Greek sorceress Medea, who, betrayed and cast aside after being used, sought revenge by taking the lives of her own children – “the killer is life itself.”[9]

Mads Bering Christiansen and Jonas Jørgensen, SONŌ, 2020–22

Photo: ZHU Lei

Courtesy Chronus Art Center

Therefore, the issue lies in our perception, as our sensibilities often sharpen and become attuned in precarious situations. Timothy Morton argues that only when what is considered normal is withdrawn, Gothic dark ecology unveils a corner that could be perceived as a vibrant reality.[10] Slime, as an entity existing between form and formlessness, now serves as a medium that connects our sensibilities with ecology. Filmmaker and researcher Freddie Mason, intrigued by the viscous states, suggests that “the viscous doesn’t exist” despite its ubiquity. This implies that “viscous” is not merely an adjective referring to a specific object. Mason goes on to explain that slime manifests as the viscous in forms with edges, but both the viscous and slime are in a state of fantasy – they are “dubious states of matter that dissolve eagerly into an operation of thought, a way of being and of feeling.”[11]

In this way, when the abjection, suppressed by the human-constructed concept of nature, is unleashed, the sublime from the idea of the subject is shattered, and we ultimately recognize the loop in the narrative of Medea and in our entanglement with slime. However, Morton believes that there is another loop, one that began long before the industrial revolution, often seen as a defining moment in the Anthropocene.

Slime mold Physarum polycephalum strains

Open source

Loop III

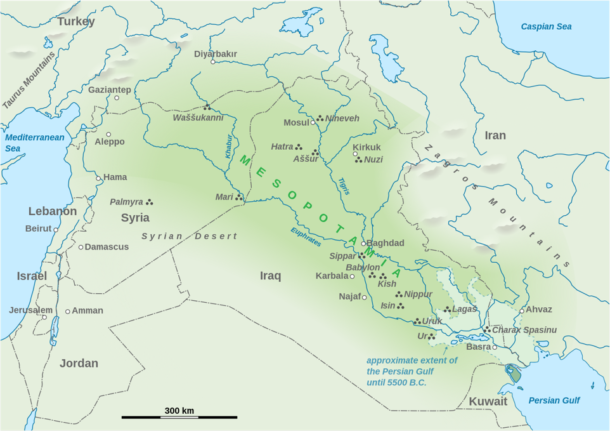

Around 12,500 years ago, as the glaciers of the Pleistocene began to melt, leading to a gradual warming of the climate, humans transitioned from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to agriculture and cultivation. Mesopotamia, due to its unique geographical location, became one of the cradles of civilization based on irrigation agriculture. It originated between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, where the arid land, caused by high temperatures and minimal rainfall, necessitated the development of irrigation and land management techniques by the local inhabitants to ensure stable harvests. Additionally, the alternating elevations in the southern region of Mesopotamia often led to flooding from the two rivers, enriching the soil with minerals and organic matter. The combination of these factors allowed for the stable cultivation of high-yield crops, particularly in the southern region, ushering in a settled agricultural mode of production.

Map of Ancient Mesopotamia

Open source

Morton views this period as the birth of “agrilogistics,” suggesting that humans shaped agriculture into a “nature” in order to transform ecosystems into resource pools. This shift in how humans perceive ecosystems involves efficient planning and utilization of these resources through technology. In this sense, the pursuit of profit maximization in industrial production in the post-industrial revolution era can be seen as an extension of “agrilogistics.” Rather than the statement “we have never been modern,” Morton firmly believes that we have always been “Mesopotamians,” even in today’s environmentalism. Morton argues that we still understand ecology through the lens of “agrilogistics,” and as a result, we have never truly escaped the dichotomy between human and nature.[12]

The slime, originating from nature and projecting human imagination, also seems to exist within the framework of agrilogistics. The powerful decentralized collective intelligence possessed by single-celled slime molds has always fascinated scientists. Their remarkable performance in addressing complex spatial problems, collective decision-making, and resource allocation has inspired various fields such as biology, artificial intelligence algorithms, and urban planning, among others. This unique organizational mode, particularly the movement patterns of cell networks formed by interconnecting slime mold cells through chemical signaling for communication and information exchange, is regarded as a robust model.[13] In their work Multitude, Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri appropriate the concept of swarm intelligence to describe a monstrous and unruly force. They emphasize that the essence of this power is a “democratic relationship,” which is not solely defined by a flexible and decentralized formal structure but also involves the production of social content together.[14] Only through communication can agents distributed within the network generate new information or knowledge, thus constructing a powerful community that maintains diversity in its actions.

Mads Bering Christiansen and Jonas Jørgensen, SONŌ, 2020–22

Photo: ZHU Lei

Courtesy Chronus Art Center

Whether in popular scientific media or in Hardt and Negri’s study of the multitude, they attempt to provide new answers to the problems in their respective fields with a post-human gesture. Nonhuman intelligence is emphasized and envisioned. However, nonhuman entities have yet to escape their symbolic and representational nature, especially in the discourse of Hardt and Negri. This simplification still confines the monstrous aspect of nonhuman entities within a human-centered, speciesist framework, inadvertently perpetuating a colonialist viewpoint and reinforcing hierarchical notions of human dominance over other species.

The Polish writer Stanislaw Lem depicts an alien planet encompassed by a vast ocean of gel in his novel Solaris. Conjecturing the slimy ocean as a single intellectual entity, terrestrial scientists tried to study it and build communication with it. Yet, all their efforts were in vain. The tranquil ocean remains indifferent to these attempts at accessing it, avoiding any possibility of being objectified and attributed to anthropomorphism that may lead it to a melancholic ending. Moreover, it materializes simulacra, bewitching the terrestrial beings by revealing their desires and fears, exposing nothing about itself but only a kind of “seemingly rational activity… beyond the reach of human beings.” What we see in slime is its abjection and monstrousness that may flow out of our control. Like the encounter between the terrestrial beings and Solaris’ ocean, in the countless attempts to access the unknown reality, humans helplessly project themselves onto the slime surfacing from the unknown reality.

[1] Cohen, J.J. (1996). Monster Theory: Reading Culture. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, pp.20.

[2] https://lovecraft.fandom.com/wiki/The_Call_of_Cthulhu

[3] Fan, J. (2021). Can We Trust Blackbox?. Foreign Literature Review, Issue 2:47-70.

[4] Kristeva, J. (1982). Powers of horror: An essay on abjection. Columbia University Press.

[5] Parisi, L. (2018). Jenna Sutela “Holobiont”, Vdrome. https://www.vdrome.org/jenna-sutela/

[6] Wedlich, S. (2023). Slime: A Natural History. Melville House, chapter 8.

[7] Woodard, B. (2020). Slime on a Wire, e-flux journal #112, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/112/352968/slime-on-a-wire/

[8] Wedlich, S. (2023). Slime: A Natural History. Melville House, pp244.

[9] Ibid, pp233.

[10] Morton, T. (2018). Dark Ecology: for a logic of future coexistence. Columbia University Press.

[11] Mason, F. (2020). The viscous : slime, stickiness, fondling, mixtures. Punctum Books, pp23-24.

[12] Morton, T. (2016), What is Dark Ecology?, Living Earth: Field Notes from the Dark Ecology Project 2014-2016. Sonic Acts Press.

[13] Sanders, L. (2010), Slime Mold Grows Network Just like Tokyo Rail System. WIRED. https://www.wired.com/2010/01/slime-mold-grows-network-just-like-tokyo-rail-system/#:~:text=a%20slime%20mold.-.

[14] Hardt, M. and Negri, A. (2009). Multitude : war and democracy in the Age of Empire. The Penguin Press, pp94.