PUNKS IN THE ACADEMY: LOCATING 90s TAIPEI IN CHINESE NOISE

| 2015年04月23日

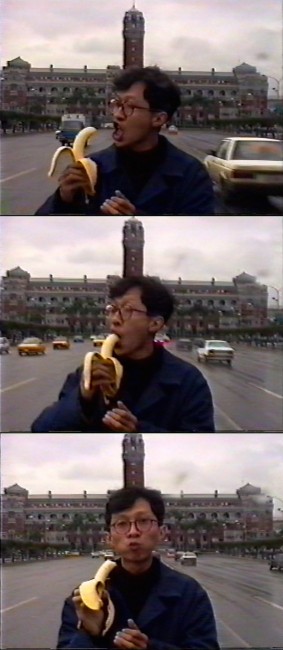

Courtesy Wei Yu

WEB EXCLUSIVE

A mannequin, already victim to an axe attack and subjected to a simulated sex scene, bursts into flames. A man in a business suit throws another one, wrapped in some sort of diaper-harness, to the ground. Behind a table, a band plays a cacophonous rush of semi-rhythmic noise, the keyboardist slamming his instrument with his hands and feet before smashing it against the stage.

Watching video footage of Taiwanese punk band Loh Tsui Kweh (LTK) Commune’s early performances from the 1990s, it is shocking what they could get away with, more in terms of personal safety than controversial politics or outright obscenity. The flames and destroyed props stand in stark contrast to the cozy confines of the Peltz Gallery at Birbeck, University of London, site of “Shoot the Pianist,” an exhibition documenting Taipei’s noise scene between 1990 and 1995. Collecting videos, ephemera, and recordings from LTK Commune alongside sound artists including Wang Fujui, Lin Chiwei, and his noise group Zero and Sound Liberation Organization (ZSLO), the event proclaimed the subcultural movement’s brief flourishing, yet left unanswered questions about Taiwanese noise’s place in broader narratives on Chinese sound art and its existence within an institutional space.

Courtesy Yao Jui-Chung

Taking its name from LTK Commune’s manifesto in the zine Agony News, “Shoot the Pianist” captures the burst of artistic activity following Taiwan’s lifting of martial law and gradual political opening at the turn of the 1990s. Even with paintings and photographs by key participants on display, the exhibit has a heavy archival feel, copies of Wang’s zine Noise displayed alongside flyers from 1994’s Broken Life Festival and 1995’s Post-Industrial Arts Festival. Audio and video recordings of LTK Commune, presented as an expression of local working-class male identity, strike a less mediated note, though perhaps obscure the group’s origins at National Taiwan University. Screenings of Huang Minchuan’s documentary 1995 Post-Industrial Arts Festival and a 2011 edit of Singing Chen’s ongoing Ears Switched Off and On project, profiling Lin, Wang, and noise performer Dino, provide more detail, the participation of women in drama groups at the 1995 festival bringing some diversity to a predominately male scene.

Yet the documentaries also draw out the disjuncture between the 1990s and the current scene. The transition from punkish noise to academic sound art is understandable in terms of these artists’ transitions to adulthood, but the cause of shifts in the noise scene as a whole are harder to extract. The Post-Industrial Arts Festival, true to its name, was housed in a Japanese colonial-era brewery slated for demolition the day after the end of performances. So is this brief emphasis on trash and violence a symptom of Taiwan’s transition from an industrial economy to a sanitized high tech society, with digital sound art more appropriate for its current state? While the festival was supported by the Taipei County Cultural Center, performers generally had a contentious relationship with the authorities. It is unclear what changed to encourage the Taiwanese Ministry of Culture’s sponsorship of “Shoot the Pianist.”

Courtesy Lin Chiwei

The present narrative of noise in China begins with activity in Taiwan during the 1990s, but often stumbles into a blank space after 1995, only resuming in Mainland China in the early 2000s through performers like Yan Jun and Torturing Nurse. Taiwanese artists have now assimilated into the Chinese sound art community— yet analog sound sources and immersion in global tape trading networks suggest that the 1990s scene was qualitatively different from today’s sound art. With Japanese acts performing at the 1995 festival, Taiwanese noise also bears a close connection to the original Japanese noise scene. Huang’s documentary references friction between LTK Commune and Japanese performer Killer Bug, but the uncomfortable resonance of this post-colonial connection is otherwise unexplored. Whether the Taiwanese noise scene is best understood as an echo of Japan’s underground, a brief historical anomaly, or a precursor to contemporary Chinese sound art remains to be seen.

One explanation for stylistic variation in the move away from the chaos of the early 1990s is a widespread interest in the social potential of sound. LTK Commune’s antics bear a relation to Dan Graham’s ideas on rock as social sculpture, each guitar riff an excuse to transcend social boundaries, with the band screaming, stripping, and stage diving to encourage audience participation. Thus, the cowboy hat-wearing rock of today’s LTK Commune may serve the same function as the noise of the 1990s. Similarly, Lin’s “Tape Music” piece turns listeners into performers, taking the audience involvement of a confrontational noise show into a more positive space. Considering this focus on the social, the exhibition’s sparing references to dance music, like Taiwan’s first rave, which occured after the aftermath of the cancelled 1995 Taipei Midair Rupture Festival, take on new significance. Perhaps the social possibilities dance music offers bear a connection to the noise scene’s dissipation by the late 1990s.

Some doubts over the continued vitality of Taiwanese noise were assuaged by a concert at East London’s Café Oto on April 2nd, whose sizable crowd extended beyond the predominately Taiwanese audience at the exhibition and screenings. Although the precise significance of Taiwanese noise merits further questioning, the juxtaposition of Dino’s harsh aural massage, a performance of “Tape Music,” and Wang’s lush digital drone with sets by younger UK performers, made a case for the relevance of Taiwanese noise’s present incarnation.