INTERSECTING HISTORIES: ON THE CONTEMPORARY IN SOUTHEAST ASIAN ART

| June 11, 2014 | Post In LEAP 26

River) to the Singapore Modern Art Society’s annual exhibition and was

rejected. Then President Ho Ho Ying wrote him a letter criticizing the work for

being devoid of substance and unmoving. In 2005, Cheo restored the letter and

enlarged it as Dear Cai Xiong

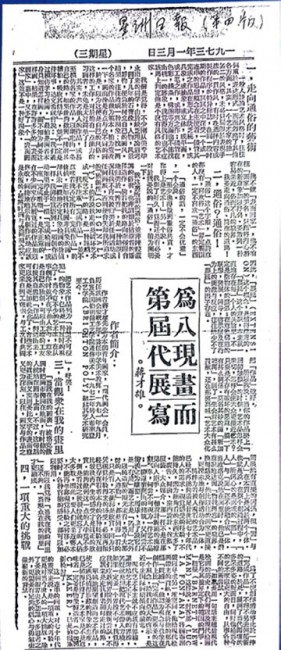

In 1973, the artist Cheo Chai-Hiang set down his thoughts on art and its predicaments at some length. The text was written in Chinese and titled (in translation) “Written for the Occasion of 8th Modern Art Exhibition.” There is, however, no mention of any exhibition within. Instead, it is a critical appraisal of prevailing trends in art in Singapore at the time, and a visionary projection for inaugurating new, dynamically charged directions.

Cheo surveys the practice of art in Singapore not descriptively or quantitatively, but with an aim of shaking it loose from its complacent, sterile stupor, for provoking artists to develop completely different ways for producing art and the public to cultivate novel ways for thinking about art—ways that he attributes as signaling or representing the contemporary. It is important to keep this prospect in mind, as the contemporary is the heartbeat of his exposition.

Cheo’s call was for art to no longer be embalmed by purely aesthetic values, to instead resonate with living experience. To do so, viewers and artists were asked to actively deal with and give shape to the changing times—to unyoke themselves from restrictive, rigid orthodoxies that some kinds of modern practices had settled into. In their stead, it was more pertinent to adopt exploratory methods and speculative dispositions. In elaborating on these topics, he hones in on prevailing circumstances in Singapore while concurrently delivering wider, worldly perspectives. For instance, he scrutinizes painting, especially abstract tendencies propagated by the Modern Art Society and pictorial depictions of the Nanyang fostered by the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, which he judges as superficial and prone to sclerosis.

Cheo remarks that the visual field is crowded and competitive; painting can no longer claim a commanding preserve for visual representation. Other media formats and technologies are capable of producing images that are visually far more compelling and seductive. If painting persists in dealing with visuality as its sovereign criteria, then it can only be consigned to an ineffective, inconsequential register. He describes the situation in the following terms:

Art that provides viewers with the visual will no longer meet the needs of men and women of the 1970s. One will not carry the experience of looking at things for a lengthy period of time because there are so many things to look at. For example, advertising billboards, shop-window displays, interior design, furniture and mass media; these are visually inviting items. A beautifully built automobile could be seen as an art object; a spectacularly designed building could be appreciated as sculpture. Aesthetically they could be beautiful to look at. To simply look at something does not constitute a critical appraisal. It is therefore desirable to also include other senses beside the visual in order to provide a more direct experience of art.

Cheo does not imply that painting per se is dead and is best interred; what he plausibly intimates is that painting is no longer the pre-eminent, persuasive medium for representing the visual and that those who practice it will have to seriously redefine the very foundations for its continuance. In this vein, he broadens the conditions for producing art elsewhere in this account. He urges artists to discard the straightjacket that currently stifles them. Cheo may be heard as avoiding categorical captivity or conformity and as moving away from the largely European convention of appraising the arts along separate, sensory modes.

What are some of the “other senses?” How might their entailment produce art that is of the times, of the 1970s? For instance, he proposes the following, which may be offered in summary as responses to the questions that are posed: (a) a work need not be determined as “finished” for it to qualify as art; it may be subject to change, alteration and transformation; by transacting these actions or processes, a principle such as permanence or immutability now vies with a phenomenon such as transience or mutability; (b) a work need not be solely manifested or realized materially and perceived as an autonomous, obdurate object; concepts, ideas, thoughts may be transmitted or inscribed by different means and devices, thereby depreciating the status of art as an object, produced for museums/galleries wherein they are safeguarded as sacred relics; (c) a work may be created collaboratively; in which instance, authorship springs from multiple, intervening agencies rather than from a single, inviolable source.

Towards the end of his survey, Cheo says that the issues that he has raised are not removed from or alien to the modern in art; he points out that “modern art is the constant struggle to go beyond its pre-defined boundaries” and that “whoever tries to pre-set a rigid boundary for modern art will sentence it to oblivion.” The implication is that the modern is susceptible to entropy, that it has to resist such outcomes and that it has somewhat succumbed to it. The modern had failed. Something had to give! The struggles ensuing from freeing oneself from exclusivist doctrines and judgments, by experimentally breaking constraints and widening the scope for art practice, are precursors “to what has been happening in contemporary art.” The modern and the contemporary are somewhat and testily related.

Having hinted at difficult, complicated connections between the two, Cheo ends his account on an exhortative note:

These are a series of questions for the artists of the 1970s to think hard about. It is a testing time for artists. It also poses a big challenge for mankind. We need to be more open when we look at the world. We also need to do a lot of arduous thinking. More importantly, we need to be courageous and have faith in ourselves when engaging in new experiments. The import of this assertion, written in 1973, has risen to immense significance today, in particular.

Even so, we take leave of Cheo with a proposition that is cast along a very different note, namely: the modern, the contemporary and the seventies may be nudged into forming historical inflected intersections; intersections that are intriguing even as they may be jangling.

Chew Daily, January 3, 1973

In 1974, Redza Piyadasa and Sulaiman Esa presented a project in the exhibition hall of the Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka (the National Agency for Language and Literature) in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. It consisted of a display of found things and materials, canvases with faintly registered marks and a publication. These were variously mounted on pedestals, suspended from the ceiling and disposed partly on walls and the floor (Plate 1). The impact of the presentation is comparable to that of what we recognize today as installation. The displays were accompanied by captions in which the provenance of the materials and objects was disclosed in detail and in ways that provoked beholding them, temporally and spatially. For instance: a chair was shown and said to be an “empty chair on which many persons have sat on,” a cluster of cropped human hair was displayed and designated as “randomly collected sample of human hair collected from a barber shop in Petaling Jaya,” a suspended bird cage was described as an “empty bird-cage after release of bird at 2:46 pm on Monday 10th June 1974,” two bottles of Coca-Cola were opened, their contents partially consumed, a cap of one of the bottles positioned carefully in front of the two and labeled as “two half-drunk Coca-Cola bottles,” and so on (Plates 2 and 3). While there were occasional references to the two of them as initiators of this project, they were not named as authors or creators of any of the objects that were shown. The publication is titled Towards A Mystical Reality. A documentation of jointly initiated experiences by Redza Piyadasa and Sulaiman Esa (hereafter Towards A Mystical Reality), and jointly authored. The presentation and its contents were undeniably unprecedented and aimed at up-ending the art world in Malaysia. Yet, protocols from that very world were observed; for instance, the “experience” was presented as an exhibition and inaugurated by Ismail Zain, then Director of Culture in the Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sport in Malaysia.

It is the publication that is remembered and esteemed until the present. This would have not have disappointed its initiators as they envisaged the text as the defining component of the entire project-cum-experience.

There is one matter that needs to be mentioned before proceeding to examine the text and exposition. An unanticipated intervention occurred during the inauguration. It featured Salleh ben Joned, a poet and lecturer in literature at the University of Malaya, who placed a copy of the publication on the floor of the exhibition venue, unzipped his trousers, and urinated on it. While this may be interpreted as a performative gesture, instigated by encountering the display (reactions were avidly coveted by Piyadasa and Sulaiman), the two initiators were completely taken aback and deeply ruffled by this act. Although it was unprecedented and socially reprehensible, it was met with indifference, publicly. In a letter addressed to Piyadasa, Salleh explained his gesture in great detail and was of the view that the mute response to what he did was symptomatic of a total absence of humor in Malaysian society. Assuming a grave demeanor without, however, muting a tongue-in-cheek tone which permeated the letter, Salleh proceeds to hoist his action onto a register which he claimed was as historically significant as that of the experiences initiated by Piyadasa and Sulaiman Esa in their ambition to alter the foundations of the world of art. “As for the pissing act itself, I still consider it, to put it in the language of Asian courtesy and modesty, as much a ‘breakthrough’ in the history of modern Malaysian art as the exhibition called Towards a Mystical Reality.”

Towards A Mystical Reality was transformed into a site for fermenting art discourse in Malaysia, the likes of which have never been equaled in the display of intensity, partisanship and depths of conviction. This was not surprising as the publication laid bare the history of the modern in Malaysian art (and in Asia), exposing it as thin, largely derivative and malnourished. It also pointed towards the way ahead, along which the contemporary was represented by actions that were historically weighted and ideologically demanding. of these were declared stridently, uncompromisingly, and zealously. The reactions were sharp and combative. I have discussed some of these matters in earlier publications. For the present I emphasize aspects that are of interest for this occasion.

As with Cheo’s judgement, Piyadasa and Sulaiman brushed aside prevailing tendencies in painting in the 1960s and in the early years of the 70s as sterile, regarding its practice as emptied of validity. They too measured the modern in art practices as displaying exhaustion. Their submission of mere artless things for show as an exhibition was a strategy aimed at undermining the status of art as commodity. It was targeted at disrupting propensities to uphold art as a “closed circuit activity” and render it as fluid and indeterminate. A year earlier, in a review of an exhibition of abstract painting, Piyadasa raised the predicament of art onto a heightened register when he asked: “How serious is our commitment with modernism and how many of us really understand the implications of the involvement with contemporaneity?”

I suggest that we answer the two-pronged question by reading Towards A Mystical Reality as a text. In doing so, and not surprisingly, we encounter Piyadasa saying that the critical understanding and the commitment demanded in his question are not forthcoming, but that he and Sulaiman envision ways out of such an impasse.

It is a treatise for fostering a new art that is historically and culturally distinctive, and pertinent to the times. The writers eschew any interest in the notion of the nation or the state, as it is restrictive. Instead, they aspire towards a kind of Asian-ness that would also contribute towards art in the world. Piyadasa and Sulaiman begin by examining the conditions in which the modern in Malaysian art is represented, and consider them as colonial in character, estranged from traditions, debilitated, and vacuous. Alternatively, and buoyed by their interpretations of certain strands of Daoism and Zen, they advocate a practice of art which is not wedded to the fabrication of forms that are permanently, materially manifested, but instead the provision of randomly gathered things that provoke thoughts on impermanence and immateriality. Such provocations in turn quicken connections between the experience of art and that of life. Space, time, action, outcomes are suggested and are even perceptible, but they are not intended as formally fixed and aesthetically fulfilling. The text sets out to “sow the seeds of a thinking process which might someday liberate Malaysian artists from their dependence on Western influence,” to decolonize prevailing thinking and dispositions wherein Europe and the West were routinely emulated and to generate alternate practices that spring from certain kinds of Asian philosophical notions for apprehending time, space and matter; practices that signaled the contemporary.

In December 1974, the Major Indonesian Painting Exhibition, convened biennially by the Jakarta Art Council, was inaugurated at the Taman Ismail Marzuki (TIM), a cultural complex in Jakarta. It consisted of complicated categories or tiers along which artworks and artists were appraised and shown. At the core of this exposition was a display of five works that were judged as exemplary; they were paintings. The panel of judges that selected these pictures was made up of Affandi, Popo Iskandar, Fadjar Sidik, Alex Papadimitran, Kusnadi, and Umar Kayam—a constellation of luminaries from the cultural establishment. On December 31, at the commencement of a ceremony for awarding the artists who had produced the five winning pictures, “a group of young artists suddenly appeared on the stage carrying a large flower arrangement across which was written ‘We offer our condolences to the death of fine art in Indonesia.’ The incident rocked the art world. From this it could be seen that the spirit of ‘newness’ formulated by the younger artists was indeed a serious movement.”

The artists who disrupted the award ceremony were protesting against the propagation of the sterile state of Indonesian art and especially of modern painting—judgments encountered when reading Cheo Chai-Hiang and Towards A Mystical Reality. They proceeded to publish their viewpoints and projections for a different art in a text titled (in translation from Bahasa Indonesian) Black December Discourse without Limit. Among the signatories were Harsono, Bonyang Munni Ardhi, Siti Adiyati Subangan, Riz Purwono, and Hardi. In it they advocated for greater publicity for and informed reception of new ideas and experimental work based on “humanitarian values and oriented towards social, cultural, political and economic realities” by discarding moribund artistic principles. This intervention spurred student-artists from other institutions to raise their voices, demanding that structures of power controlling the worlds of art be altered. They called for change, urgently and presently.

Did the Black December incursion precipitate a movement? Did it generate shifts, enabling new creative methods and approaches? It did in several ways. For instance, by striking at the heart of the art establishment on the occasion of a premier event on a national stage, the Black December intervention attained widespread attention and notoriety. It paid a heavy price too, as it was made up of students enrolled in the Akademi Seni Rupa Indonesia (ASRI, Indonesian Academy of Art) in Yogyakarta, who were punished with expulsion. There were wider ramifications. Intense debate ensued; lines were drawn separating the defenders of orthodoxy from those who supported diversity and art that was different. It signaled a movement in another instance as it spurred actions by young artists who aimed at challenging prevailing conformity by dealing with unorthodox practices and showing novel productions. It signaled a movement in the sphere of institutions, as not of them were of the same view as ASRI and assumed dissimilar positions. The School of Art in the Institute of Technology in Bandung, for instance, was hospitable to the members of Black December and invited them to display their works on its campus.

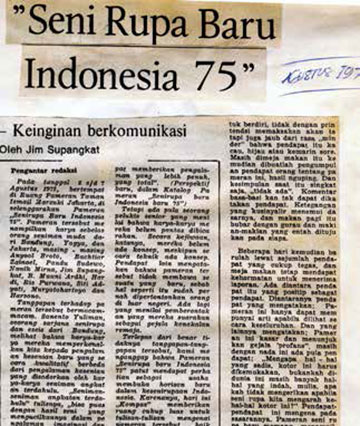

These actions and reactions may be construed as cumulatively leading to movements; movements that were swiftly executed. As movements they were constituted by artists mobilizing in the principal cities in Java (Jakarta, Bandung and Yogyakarta) for publicly proclaiming their thoughts, propagating their practices and productions, and canvassing for critically engaged publics and reception. The tone of these manifestations was militant and combative; the stance was that of activists. Individuals spearheading these campaigns were students who traveled to the principal centers, grouped and re-grouped to ignite varied yet related flashpoints. The Black December intervention is regarded as cresting to give rise to the Indonesian New Art (Seni Rupa Baru) initiative in 1976. It was inaugurated by ten artists in an exhibition at the Taman Ismail Marzuki Cultural Center (the very site for the staging of the Major Indonesian Painting Exhibition in 1974, which instigated the Black December incursion). The following are listed as participating artists: Ayool Subroto, Bachtiar Ainoel, Pandu Sudewo, Nanik Mirna, Muryoto Hartoyo, Harsono, Bonyong Munni Ardhi, Hardi, Ris Purwana, Siti Adyati Subangun, and Jim Supangkat. But Mochtar invited the Indonesian New Art artists to display their works in the School of Art in the Institute of Technology, Bandung, for “study, appreciation and evaluation.” There is a sustained parallelism between it and the Black December group.

It appears that Indonesian New Art in turn spawned Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru (New Art Movement, hereafter GSRB), which has been hailed as marking a turn towards the contemporary in Indonesian art. For the present purpose it is important to underline that the appearance of this formation was accompanied by a text, in the form of a declaration or a manifesto titled (in translation) “The Five Lines of Attack of the Indonesian New Art Movement.” In summary they are: (a) eliminating distinctions separating studio practices in the visual arts as autonomous disciplines and cultivating inter-related approaches, (b) abandoning the concept of “fine art” and redefining art more widely and inclusively, (c) freeing art from elitist, exclusivist attitudes and relating it to social experiences, (d) inculcating exploratory methods in art education and discarding pedagogies based on the emulation of master practices and styles, (e) engaging in research into art in Indonesia and its histories as a measure for countering universal (Western) claims for art. The new was defined with specific regards to altering circumstances and structures of power that prevailed in Indonesia.

The formation of the Philippine collective known as the Kaisahan Group in 1976 was intricate and complicated, as it was consolidated by artists who had split from earlier associations and regrouped to advance appreciably different aims, and to cast existing aims with fresh mandates. The avowed intention was to locate its thoughts, programs, actions, and practices on markedly political terrain; that is to say, on grounds that enabled artists and art to connect with society widely, actively and on multiple sites (moving away from appearing only in spaces or precincts designated for the exhibition of art). These are not new ambitions in themselves; what is acknowledged as different was that the Kaisahan Group represented a new cohesiveness whereby intentions and outcomes were realized. Similar to the GSRB, the Kaisahan Group marks a crest rising from earlier surges. Similar to movements in Indonesia, here too the Kaisahan artists issued declarations setting out principles aimed at altering the art world in the Philippines; these were published and widely disseminated. The manifesto of 1976 is recognized as presenting its ideals fully and forcefully. I report it in summary and focus on the salient claims.

The manifesto begins by emphasizing that art embodies a sense of national identity. The second principle has to do with directing the affect and appeal of art to a broad range of publics. This dovetailed into a third goal, for art that was envisaged as being alternative to elitist or exclusive ideals and to the commercialization of art production. A fourth assertion positioned content in art in the foreground, although not necessarily by completely jettisoning involvement with form and material; the insistence was, however, on the communicative capacities or readability of art, for which content had to be vivified ostensibly. Of course, the affectivity of content, in turn, sprang from topics that depicted lived experience. In these regards, categories such as “realist art” and “social realist art” as they are applied in discourse in Philippine art may be seen as crystallizing the intentions and ambitions of artists such as those in the Kaisahan Group. Finally, access to art was paramount, and in dealing with this, we loop back to the second claim in the declaration: sites for producing, presenting, and receiving art were recast in communitarian terms. Artists and art had to be mobile, constantly relocating in varying social spaces.

The aforementioned events and movements mark formative intersections for dealing with recent art in Southeast Asia. Of course they do not exhaust comparable historical instances from the region; such is not the motivation for this article. The aim is to prospect terrain selectively and sufficiently for presenting and talking about a number of contemporary artworks from Southeast Asia, and to provide textual networks for ascertaining the wellsprings of contemporary strains in the art of this region.