GENETICS

| July 7, 2015 | Post In 2015年6月号

Courtesy the artist and

Museum Het Domein

“Reaching out, diminishing the distance, longing for the Other is dangerous, brave, and ultimately rewarding,” quips Belgian-born artist Koen Vanmechelen, the man behind the long-running Cosmopolitan Chicken Project (CCP).

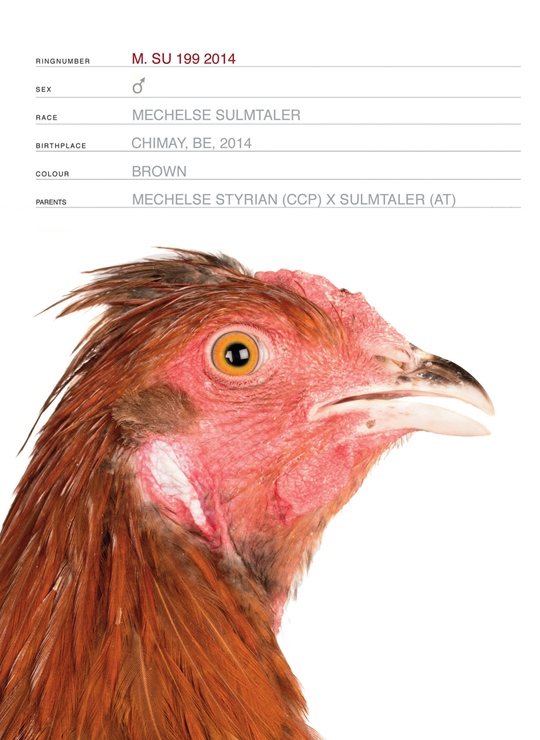

Since 1999, Vanmechelen’s biological tampering, aided and abetted by human geneticist professor Jean-Jacques Cassiman, has been working towards the creation of a supremely well-connected bird carrying the genes of all the chicken breeds on earth. Birds from far-flung destinations like Slovenia and Senegal comingle, generation after generation, hatching new hybrids who move beyond evolutionary deadends to create longer-living, hardier, and more peaceable fowl. For the artist, this process of promoting desirable phenotypes is not mere animal husbandry, but an act of art.

The deliberate manipulation of breeding until maximum mixture has taken place stands as a positive metaphor for globalization, predicting the ideal out¬come of capitalist exploration—an end to petty squabbling as a global human subject emerges. Promoting contact and learning from the other in our decentered cultural climate by pointing to the robustness of interbred chicken DNA, the CCP dramatizes the vitality that can be won from shrinking intellectual and social distances. Vanmechelen pitches cosmopolitan biodiversity as our primary hope for resolving racism, intolerance, and other harbingers of social dysfunction. Here, too, is a commentary on identity in the twenty-first century, suggesting the end of familiar social forms as post-industrial individuality is washed away in big data algorithms, ostensibly for the greater good.

Courtesy the artist and Museum Het Domein

His vision stands in marked contrast to the pessimistic view dominant in leftist and intellectual circles, where globalization is often lightly applauded as having diminished “classic” racism, but then attacked for creating new and alarming cleavages like class inequity, waste, and a massive global underclass. For many, the dismantling of old provincialisms precedes the building of new barriers. Vanmechelen’s approach to bioart as “lived” also departs from many contemporary critical treatments of genetic engineering.

The CCP, for example, stands far from Li Shan and Zhang Pingjie’s Pumpkin Project (2007) and the long running “Reading” series of which it is part. Working from their own homegrown thesis of bioart, the two Chinese collaborators turn their fantastical concepts into real, living art with the help of vegetable breeding experts. Deliberate gene tampering altered the vegetable’s physicality to produce aesthetically compelling forms, but the new pumpkins were short-lived weaklings. Here, bioart is beautiful as object, but degenerate as subject. Some of Li Shan’s 2003 to 2006 “Reading” works offered a more explicitly dystopian, Cronenberg-esque subtext to genetic tampering, most notably his digital photos of insects composited from images of his own body parts.

The utopic intent behind Vanmechelen’s project may rattle some, and the ultimate implications of his bio-engineered hybridity remain to be seen. Still, at least one thing is certain: with the CCP, bumpkin birds everywhere have been given their notice.