Prickly Paper: Workshop Once More

| March 10, 2022

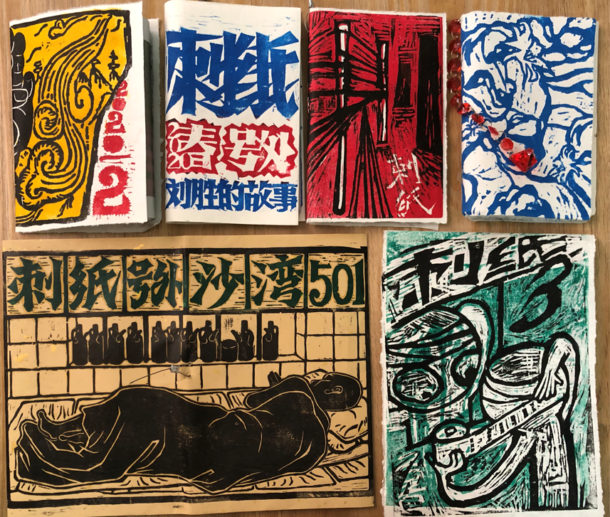

A reader-unfriendly magazine at first glance, Prickly Paper, founded in 2019, can and cannot be judged by its cover. If the definition of friendliness extends into a teleological map of operational duties—including clear distributions of responsibilities, neat wireframes of processes, and steady performances of functions, Prickly Paper has not yet been so close. Their formulae are rather modest and straightforward; handmade wood carvings and home-printing took Chen Yifei and Ou Feihong from Xiaozhou Village in Guangzhou to various ports. The two editors are known in the local community for gathering people to make prints. In addition, they travel frequently and carry out activities such as workshops and games. The fun experiments are their way of exploring outside the ossified attitudes—namely, the “mainstream.”

Can a combination of friendship-based work and work-oriented friendship become an alternative in the current art ecology? To what extent can the proliferation and subsequent commonness of workshops disrupt the cost-profit mentality and evade the systemic co-option? To what extent can practitioners unload the baggage and immerse in the joy of collective and self-empowering work? How long does it take for these practices to bear fruit? Or will time prove the seeds of change significant?

Driven by a desire for alternatives, I, as a writer and editor myself, was particularly interested in how Chen and Ou worked together, hence this conversation.

——Ren Yue

-610x358.jpg)

The editorial office of Prickly Paper. Courtesy Prickly Paper

LEAP: Let’s begin with Prickly Paper itself. I am just speaking out of my own intuitions; feel free to correct me if necessary. Prickly Paper’s work seems quite playful at times. Especially after being exhibited at FEI Art Museum, it has evolved into a working formula that has given people more options towards an imagination of aesthetics, thinking processes and methodology.

I guess we could say Prickly Paper is a highly condensed physical embodiment containing editors’ anticipation, values and faith. How was such an embodiment reflected and refracted through its current productions and aesthetic choices? Besides exhibitions, sharing sessions and even podcasts, how have you been holding onto publishing hand-made books so steadily while also handling your desire for it to be popular, or, let’s say, mainstream like other publications? Do you mind elaborating on how decisions were made and whether they were driven by careful planning? Or, perhaps was it random encounters or serendipity that have accompanied you?

Chen: Prickly Paper was already at its embryonic stage when Feihong invited me to join this editorship. I believe among all of our initial ideas, self-printing especially evolved out of the encounters we had with friends that were practicing it. I remember Feihong has collaborated with Instance and Fengfo Magazine and I am also their regular readers. Prickly Paper also then collaborated with Instance.

I graduated from a print-making background and have spent enough time treating printing as art-making. Ironically, I have never tried woodcarving in school and my first ever try was for Prickly Paper’s cover; whereas our friend, Qin Dao has been quite familiar with wood carving and has made a poster for On Kino first.

Feihong is 18 years older than me. He told me when he was in university, home inkjet printers were as popular among uni students as DSLR cameras. It was these inkjet printers that have enabled people to easily print on papers, or even make books; they didn’t have to rely on printing shops or factories. So our idea to use inkjet printers and our choice of newspaper originated from Feihong’s real experience. Feihong then became the marketing manager at Fengfo Magazine and has also tried using Inkjet printers and binding with staples.

Tiancheng Electrical Appliance Wholesale and the printer store in the market, Guangzhou

As for my own aesthetic preference, I like the slightly brutal style. Some of Feihong’s previous work in Prickly Paper—for example, midnight watcher and into the toilet graffiti—all had the sort of rebellious and mocking element against the mainstream; they are also conveyed through bodily actions and mechanisms. In the making of Prickly Paper, we have exposed the intersections of our preferences.

It is an extension of what we have accumulated in terms of the development of our habits and choices. On one hand, the workshop is relevant to my own interest in education; the organisational side of things is also relevant to Feihong’s disownment of apprenticeship. The actual space is relevant to Feihong’s Family Tour project (to open up one’s intimate home) and my own project, Jasagala’s hospitality. We are quite flexible in terms of how our own experience outside Prickly Paper influences and shapes these directions.

So to answer your questions, for me it was serendipity or some sort of a fate more than anything. It all started from the initial project proposal when Feihong was invited by curator Li Juchuan from the Fei Art Museum. Prickly Paper has changed since. Its evolutionary journey should not be read in brief because every change was an embodiment of our conditions, our rationalities and our decision-making. However, these thoughts were always also driven by fates and randomness – from the people we met, agreements and disagreements. The thoughts behind these “agenda” were flowing and the next steps were the imaginaries. They would also reappear or re-encounter us in discussions and experiments.

Ou: By “mainstream”, did you mean traditional book publishing? It is beyond difficult to get a book number nowadays. We didn’t anticipate doing that and traditional publishing is boring anyways. On the other hand, wood-carving as well as self-printing and binding consume way less effort or time. It suits every unprivileged and it needs no complicated scheme.

Prickly Paper Extra Liu Sheng’s Story. Courtesy Prickly Paper

LEAP: Do you think you will share a similar perspective on collaboration, especially that of the essential editorial work, be they technique, workflow, or the mindset? In a more general understanding of human affects, how is the friendship-based network of Prickly Paper’s established and maintained? According to my observation, the content in the last two years has been increasingly hinged on this value of friend-making, allowing them to exchange various experiences and opinions. My concern was this: how have you maintained your own preferences and principles while representing such diversity. How do you righteously give support and reciprocate in such a working context? And if it stands upon the reciprocal relationships between and among friends, how has affect —positive or negative—been recognised? How do you deal with individual differences that deviate from the central representation, and hence potential conflicts?

Ou: I mean, friendship network is essentially a serendipitous result of pushing and pulling among a group—whether it is actual communications, or arguments, or jokes. Every person or unit of being becomes a part of this aggregation of collectiveness and connectedness.

Chen: Co-working is rooted in our daily lives and routines. Thoughts jumped out to find us when we were eating, or chatting. When we are throwing ideas out of the months without considering whose ideas they actually belonged to, we also did not mimd appropriating each other’s thought processes. We often need to confirm, quite physically and literally, these ideas in our production; for instance, printing out the materials, binding them with a range of things, and giving each other feedback. Overall, a successful co-working is a definite derivative of our connectedness. As we give and reciprocate, we are leaving a certain space and setting certain boundaries for each other. No doubt can we agree on creative ideas and practices.

The maintenance of one’s friendship network should be like water flowing across the map from one port to the other. Get to know people. Befriend them. Invite them to our familiar places. Be flexible and communicative. Get out of your comfort zone… It is never dependent or co-dependent upon ourselves; it should be an actual exchange to find the best pace and work in a sustainable way. The gravitation is loose but it is never absent.

Unit. Unite. United. Each person can divide his multiple selves into substantial parts to unite with different friends accordingly; a unit is then formed. Each unit has a (pre-)subscribed name (vague) that defines it. For example, Sun Yifei, Fang Zheng and I are the editors at Jasagala’s WeChat official account, while Ou Feihong and I collaborated on Prickly Paper. Every two or three people can form a new working group. So in some project posters, sometimes there could be more logos for the collectives than the total number of people involved. Somehow we do not have to cling to our own subjectivity as individual and independent artists. We can divide ourselves up and form new units or collectives with others. When we encounter disagreements, we can respond as individuals, not necessarily bundling our ideas with anyone else’s. If it involves joint opinion, we will disclose our own thoughts to each other – for example, in this interview, we would express it separately and then come back as a whole. We do not seek to agree, but to ensure a common threshold that governs agreement.

The editorial office of Prickly Paper. Courtesy Prickly Paper

LEAP: So does Prickly Paper still recognise friendship at a central position of its structure-building? Do you often keep in touch with other regional publications, creative practices or even individuals that hold similar viewpoints and values? As editors, what do you think of other working collectives that share these similarities?

Chen: The slogan on Prickly Paper’s stickers says, “publication is a way to connect.” The slogan of Benguangda gallery (Ou Feihong’s online WeChat store) is adapted from the Comité Invisible; “gallery is excessive and is for vain; unless it is for friends, including those we don’t know yet”. Jasagala’s rationale is also to connect friends from different fields. So it can be said that Prickly Paper entails a crossover of our individual practices and preferences and it then grows into various new directions.

Publishing is not the only thing we wish to do. Departed from book making, we started our own workshops, traveling around to meet new people and to share what we own or know. We have even collaborated with actual physical spaces. There hasn’t been an absolute standard or a set of criteria. Nor do I think about being similar in nature to any publication or collaborative organisation, because there is no definition of such a kind. We like to learn about other people, other matters, other thoughts and practices, as they help us revise our directions and shape our ways. Book-making is fairly new to us and we have never considered making books an occupation.

Ou: “Handmade publication is a way to connect with friends, including those we don’t know yet.”

LEAP: I happened to pay a visit to your site this May, and a life-work cooperated vibe came as my first impression. The next door neighbourhood unit—a single bed surrounded by bookshelves – was particularly interesting, especially its accessibility; the space itself was not so encouraging although I would say any visitor would be curious about it. We need some courage to find ourselves comfortable there. How did this idea come about and was it your desired space? I imagine it different for different guests to engage with such a space. Do you pick who you want to work with because you might wish them to share the same mindsets – to recognise space as an essential part of your work?

Chen: In fact, the single bed surrounded by bookshelves is the reading room of the neighbourhood unit Flight Club. Next door with a large bed and a bunk bed is Zhaodaisuo (guest house in English) and it is built and supported by Prickly Paper and Jasagala. We actually felt that the sofa bed in the reading room was quite comfy. Feihong and I would sometimes nap there during lunches, while some of our friends particularly liked such a sleeping environment.

We welcome different friends and really there isn’t any strict standard for selecting our guests, as long as they give us a simple introduction and confirm in advance the time and length of stay. There are cats and plants to be taken care of, it is easier when we are there physically; so we have not yet turned guests down for reasons other than our own schedules. Our own residential area is separated from the guest house, so even if people come and go, we are not too disturbed and can still claim a part of the space as our own.

It is quite ideal for me already. It would be nice to have less expensive bills – rent is already low, but utilities are high in urban villages – and more sunlight, less construction around, an extra rooftop maybe. However, a space can be developed slowly, so is our relationship with it. Just like our books and our relationship with friends, we don’t expect a perfect encounter with a perfect space but to shape what we define as the “ideal.”

Ou: When you visited in May, the studio and the guest house were just starting to run. So far we’ve had loads of friends and we hardly turned anyone down; we’re not picky.

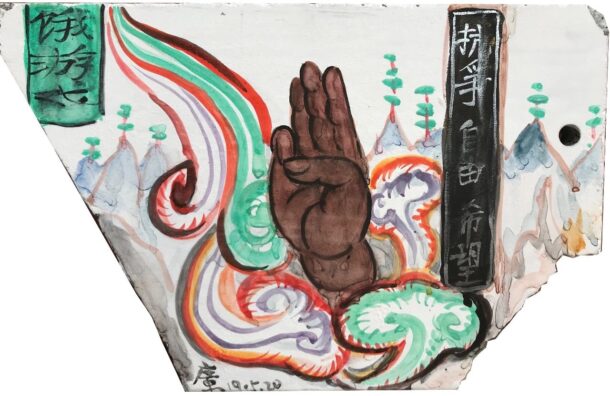

Ou Feihong, The Hunger Games, 2019, paint on tiles, 33 x 20 cm. Courtesy the artist

LEAP: Your signature working patterns which consist of woodcarving and printing-at-home naturally reminds me of the word “workshop”, despite that the word itself and the working scheme it refers to have gone through layers of transformations in both linguistic and economic senses. Workshops are quite popular nowadays, and workshops supported by either material or intangible elements have almost saturated art institutions’ public programmes and events. Yifei, you once joked that Prickly Paper is becoming a sweatshop (factories with poor working conditions and meager remuneration for labor); Is Prickly Paper something between a workshop and a factory? Within your current framework, how do you define the differences between them and what is Prickly Paper’s irreplaceable uniqueness?

Chen: I like workshops because I see them as a chance for the initiators and participants to share and interact. They are immersive, experimental and pragmatic. They are like games. We own a set of tools and skills but it is by workshops that we utilise them.

We also call them “sweatshops” because we have to do more manual work to manage income. Every book is different and we don’t standardise everything like a factory, so there is no so-called efficiency. Sometimes we find surprises in our production and make use of them (for binding, updating the colour palette, or even adding new contents suddenly). We don’t force ourselves to produce or obey. If we don’t want to do it, we don’t do it. If we really cannot carry on, we will take it off the shelf or simply raise the price. If someone is willing to pay a higher price, we can try to restock. Our books are not commodities, but gifts for exchanges and reciprocity.

Ou: I don’t mind it being popular. Wouldn’t it be good if it’s popular like karaoke or barbecue? Lots of friends have started various workshops. They are amazing.

Spreads of Prickly Paper Extra: Shawan No.501. Courtesy Prickly Paper

LEAP: Woodcarving, printing and binding at home consumes a considerable amount of time and energy. It is also substantially a work with materials. Seemingly a single-way comprehension and outcome-oriented deployment, I realised that the relationship between the maker and tools is just as vital for a better working environment; it may even affect the mindflow during the whole process. At least, my thought was pretty much influenced by Nina Maclaughlin’s Hammer Head: The Making of a Carpenter (2015). But do you feel attached to materials and tools in such a way?

Chen: It’s easy to get attached. As we work with them, we are also finding new ways to use our own bodies (for instance, to finish the work with less effort and more precision). It is similar to living with people; we have to feel their characteristics. I know it sounds figurative. I don’t want to describe it precisely because it’s abstract. Perhaps it’s like our Energy Waving Practice. The physical reflex is instinctive and innate. It is not a result of reasoning or thinking.

Ou: I am easily attached to my customers and readers so in-person purchases and compliments can make me embarrassed. But things are just things. I don’t easily have excessive feelings for crafts.

LEAP: In addition to editing and bookmaking, as an artist collective, how will you describe your collaborations with other practitioners or institutions? In those projects, what are the parts that usually demand more interpretations and negotiations? Will the editorial team take different strategies in dealing with group work among friends and more formal collaborative projects? Do you have a standard rationale or criterion that helps you make decisions on whom to collaborate with?

Chen: We are open for collaborations but we need to really meet and spend time with those who offer to collaborate. It is essential to make sure that our needs and wants are aligned. Sometimes we accompany each other to research and explore (e.g. with the Social Practice Lab at the Times Museum, Guangdong); sometimes we work as service providers (e.g. paid jobs at woodcarving workshops for institutions); sometimes we initiate workshops or share our local friends in exchange for a place to stay (e.g. the Southwest Tour under On Nomad). There are different ways to collaborate and we play different roles but the most important is to clarify the boundaries, distributions, and expectations.

Ou: Our editorial team is just an editorial team. We still need other works in the art world to make a living.

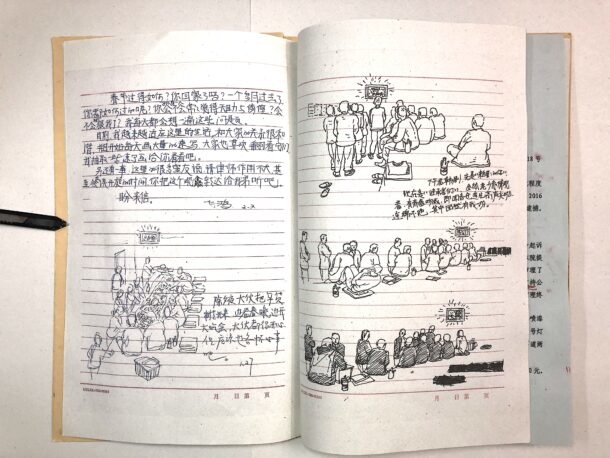

Screening documentary We Were Smart (2019) in the Dong Village. Organized by the Social Practice Lab of Times Museum.

Photo by Zhang Hanlu

LEAP: Prickly Paper often extends to other sites. You would drop around friends’, and the scope of your activities are not limited by your geographic locations. You would organise guerrilla workshops all over the country and have worked with local people in Xining (Qinghai Province) and Dong villages in Southeast China. What does cross-regional work mean to you? From content production to methodology, is it a decentralised connection that has extended your site in Xiaozhou, Guangzhou? If the collaborations are usually triggered by interpersonal friendship, how did they transform into a work relation? Does the educational purpose of knowledge exchange outweigh such personal affections when you “travel to work”?

Chen: Sometimes we work across regions (e.g. Dong Village) because there are more beyond our daily experience. We see it as “learning” continuously. When we go to places for new connections, we are building possibilities for future collaborations. It could be tiring at times and we just wanted to go back to our village only to find ourselves tired of the village after staying there for a long time. It is fun to switch between these conditions of life or work; we get new ideas from travelling around. I think we’ve been going in and out every month this year.

The transition from personal to work relationship is also related to our attitude towards work ethos. We won’t separate the personal from work and it is often because we spend time together that we find mutual interests and beliefs in work. We also tend to share and exchange information, such as introducing friends and their practices and imagining unrealistic collaborations. In different friendships, we are also teased with the idea of fake intimacy or “irrelationship”—describing our shared defence system to develop emotional attachments or project emotional baggage onto them in order to maintain a loosely joint relationship that lasts longer.

Ou: A walk a day keeps the doctor away… Out in the wild to explore the great Earth is to extend our being in this world.

Prickly Paper Miniature Book workshop in the Meide Village. Courtesy the artist

LEAP: Back to the initial stage of Prickly Paper—did the concept of “toilet reading” imply an intentional cultural demystification? Or was it a voyeuristic glimpse and whisper to public affairs? What are Prickly Paper’s editors’ and friends’ wishes for it as it stands in near or far localities.

Ou: Oh yes I do miss the old Prickly Paper in the toilet. It’s getting expensive now.

Chen: The direction of Prickly Paper was never pre-determined. A book recklessly walked out of the toilet to meet the public. It is then extended to workshops and physical spaces. It wasn’t expected. Prickly Paper will continue to change and morph according to our living conditions and encounters. Let’s see how it goes.

Ou Feihong, CEO of Kon ton Yellow & Benguangda gallery, one of the editors of Prickly Paper magazine. He lives in Guangzhou.

Chen Yifei, born in Zhangpu, Fujian. Co-founder of Jasagala art collective, editor of Prickly Paper. He currently lives in Xiaozhou, Guangzhou.

Translated by Harriet Min Zhang

Ou Feihong

Ou Feihong