Shi Shi Nan Liao

| March 29, 2022

shì shì nán liào (try out what’s hard)

shì shí nán liáo (hard facts are hard to chat)

shí shí nán liáo (boy’s chat in real time)

shì shì nán liào (the world is hardly predictable)

shí shī nán liǎo (too hard to realize)

This past July, after wrapping up the production on my new film, I started to contemplate the difference between “working” and “making works.” Slightly burned out from the meticulous planning and the heart-exhausting teamwork, I craved a simpler, purposeless creative state.

A few weeks later, I met Dong at a friend’s dinner party. Maybe I only noticed this tall, straight guy because he laughed at my bad jokes. But as we grew to know each other, it turned out that we shared a common yet distinct sensitivity towards language. So, out of curiosity, when I received the invitation to contribute to this issue of LEAP on the topic of friendship, I invited Dong for a chat. What interests me is the shape, the boundary, the outline of this thing called “chatting”: how it unfolds like breath, through the back and forth between two persons. What is it that we create, without the guidance of an agenda, a map, a clear-cut theme? Part of me does (selfishly) believe that this still-burgeoning friendship between Dong and I, full of expectations and misinterpretations, may engender more ambiguity through our conversations.

In middle school, one of my classmates was a Nietzsche addict. He would spend all day discussing the lines from the German’s books. Even after we graduated he called me one day to ask if I remembered him. Then we continued our conversation on Nietzsche. Maybe that phone conversation disappointed him, or maybe it was just time—but I never heard of him again. Can chatting be a way of creating works? Can something be captured from those words that fade into thin air? (And how to do that?) When conversations end, what will be the first thing to surface, on the ocean that is memory?

Amiko Li

All pictures courtesy the authors unless specified

A: Question: if you were a transportation vehicle, what would you be and why?

Dǒng (to understand): I’d probably be a pair of 1×4 roller-blades, with their laces tied to each other. Standing, trembling, gliding, wobbling.

A: Haha, skating in parallel—is it like the three-legged race we used to play to train our cooperation skills?

Děng (to wait): I just sent my friends the question you just asked me.

One replied with a pair of 2×2 roller skates, hence my first answer. Then we turned to me. One said that I’m like Theo Jansen’s walking, kinetic sculptural “vehicles”. Someone else said “a crutch”.

Re: the crutch – it has to be made of hardwood with the highest density, so heavy that even a healthy person won’t be able to lift it from the ground.

Re: theo jansen – this foreign, wooden ox is also made of heavy, dense hardwood, but with such flexible structure that it wouldn’t collapse on itself. The drawback is that it cannot move easily and has to wait for a gust of wind to power its movement. For half a century, it waits and waits in vain, but keeps on waiting.

A: Hahaha, how come a crutch is a vehicle!

Anyways, you are the most advanced version of a raw tool, made with the best materials, brought to life by the most skilled craftsman.

Děng: A crutch can be an oar. It would be too weighty to be held and would be dropped into water. It is also capable of dragging and dropping whoever’s holding it down to the bottom of the lake. Two types of movement, two types of vehicles.

A: (Is this how you normally talk) Wind chimes! How they tinkle with the wind. I watched a video where someone left their house for vacation. When they came back, a note was left on their door, which said: “You forgot to take down the wind chime when you took off, and we had a hard time sleeping for the past few days.” If you think of it this way, wind chimes are not unlike glassblowing.

A: Yes, the world is knitted together by threads that are entirely invisible, subtly noticeable, or utterly evident. While the relationship between words shifts with their contexts—of history, of cities and geographies, of the ones speaking, of the ones listening, and of many more. Do you observe the ways different people sing? What do you care about, or find the most curious? I came across this term: “Singing Quotient (SQ)”? It seems to relate to a singer’s understanding of lyrics and melodies, and their ways of handling songs—whether to perform an understated gloss-over of pain or a heartfelt arousal for some type of empathy. As for the song of life, aren’t we all singing it out of instinct? Is there any space left for a reflection on “the directions of sound and language as metaphors”?

The last time I brought up this episode was probably a year ago, in my family group-chat. I asked my mom, out of the blue, if we still had any of her wind chimes at home. My brother replied: “The wind chimes make me sad.” I said, “Yeah.” But my dad asked, “Why?” Only then did my mom show up in the chat. She just said, “I know.”

A: Your mom knew why, your dad asked why. Your brother felt sad.

Reading this makes me sad too. So often it feels like we only look at objects as concepts, interchangeable with their price tags, or their necessity in our lives. We tend to overlook how an object is actually made, or who makes it, in what emotional state… So much is crushed and kneaded into those ribbons, those brass pieces, those hundreds and thousands of wind chimes. I believe that such emotional objects used to exist in earlier days, like lanterns or origami lucky stars. Childhood events like this are always a bit melancholic in their undertones, as if a tunnel once reaching towards the past has already been closed.

(I’d like to see your wind chime)

A: It’s on purpose, you’re welcome. A little knitted trick, like a wind chime.

I haven’t started making the wind chime yet. Yet, in relation to it I’ve brought up some questions regarding the sounds within language a few times. I’ve thought of many words, images, and concepts that ought to have more precise pronunciations. Pronunciations that, within our logographic system, can hit the bull’s eye. A lot has passed through my mind, such as, how is a precise sound possibly made? Crawling further down the rabbit hole, I’ve been concerned with what kind of materials should be used to make the wind tubes; what kind of string would go through the tube (in what kind of way); what kind of composition the materials inside the tube would follow, so that the string, passing through from one end to the other, could compose what kind of logic for sound, so that it is sound itself that attempts at making meanings…

A: I’m here. Don’t know if you’ll notice that I left a line here.

A “wind chime” sounds far from a “sound installation.”

The sentence above is ambiguous in a few ways.

“Sounds”—does it refer to the sounds these two objects make, or to the objects themselves?

“Far from”—is that talking about a distance in space, or in meaning?

If I am making a wind chime, why does it have to be something exhibit-able: a sound installation? What indeed is the difference between exhibiting a wind chime and exhibiting a sound installation that is derived from a wind chime?

A: Yes, when I say the Chinese word for sound “shēng yīn,” in my head I translate it to “voice”, which carries a tone, even a sense of direction. Shēng yīn, however, is not as grand, nor does it imply any distance. The distance in shēng yīn, inasmuch as it does exist, seems to be between the subject speaking and the audience listening; whereas the distance in meaning is more about a distance that is impossible to overcome. It’s as if, no matter how far you’ve come, the destination lies ever farther away. Can we really overcome the distance between a shēng yīn installation and a wind chime? Or do we have to act like one of those battery-powered robot dogs: only able to turn in the right direction with the aid of a big, gentle human hand?

(For me a wind chime is already a shēng yīn installation. It wraps you around in no distance.)

A: I just thought of a work I’m fond of, Mouth Factory by Guo Cheng. Although it was not his intention, I like its hidden sense of futility.

You mentioned performing and making sounds with your hands as if they are a tongue. What would it be like if this was to be realized? Hands can trigger a frequency that cannot be captured by ears.

In the act of imitating/performing, I am giving shape to A with something A is not. Differences are a pre-existing neutral ground not to be judged as good or evil. The difference between the metaphorical vehicle and the tenor creates a space for my mild exploitations—where I mess around with what the shape of the thing itself can’t shape.

The idea of “shape” (xíng róng) has been on my mind for a while. What yì (meaning) and xiàng (image) can the shapes of things contain exactly, both directly and indirectly? This frequency may sound so blatantly deafening, while that frequency might sound like countless claws, sneakily scratching at your heart.

Guo Cheng, Mouth Factory, 2012, apparatuses, videos, images

Courtesy the artist

A: It gives me this feeling that this performance might be better written than performed… Writing, on the other hand, empties out a space for imagination (how a freshly caught catfish almost slips out). Regarding giving shape to A with something A is not… is it that the farther things are from each other, the better? How far am I from you?

Xi Chuan once pointed out a logic to unpack Hai Zi’s talent. Basically, if the metaphor for A goes beyond the general associations with A, the more distant and ridiculous the metaphor is, the greater the talent.

That is, the distance between metaphors and their tenors needs to be continuously expanded. However, a metaphor isn’t necessarily calculated, but spewed out by instinct. As long as you think about it, you see how splendidly it makes sense.

A: hi, how was your trip back to Beijing?

Dong: I did a four-day Beijing International Film Festival marathon, one Tan Chui Mui film a day. In her films, there is an animated sensibility belonging to female directors, often in her handling of emotions and narratives in those banal scenes, which has a semitone-like quality.

A: What do you mean by a semitone-like handling of emotions and narratives?

D: I’m talking nonsense. But I guess what I’m getting at is, an attempt to describe the transitive, steering emotional passages in between the more palpable emotions of two main events, through this term in piano that I never studied. Similarly, in those secondary scenes shot in corridors/hallways, that serve as transitions, something mildly scratchy would happen, neither too achy nor too itchy. Yet in watching those scenes, I would get a prolonged feeling that tickles me with an illusory pain.

Sort of.

A: Speaking of semitones, I usually think of the writings of harmonies, which is similar to the transitions of cinematic emotions that you talked about. I’m wondering if the understanding of cinema would change how you feel when you watch a movie? Whether you would overanalyze the sudden insertion of a piece of background music, the structures of erotica, or be immune towards the use of special effects and so forth.

A:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xwJmAFB1ixc

I was just watching this video, which makes me partly resist the overstudy of music. Music is supposed to be a sensual experience, and to justify it through words and definitions is to make sensations rational. It feels inevitable that things will be justified, as if justification is as inescapable as human causality, or as Pavlov’s salivating dog.

This goes back to our earlier discussion about the loss of emotive power in certain overused words, so much so that they are just set phrases. Just like how a pot of over-brewed tea would gradually go bland. Think about the phrase “heart-wrenching pain”—it has become such a vague indicator for pain that I don’t feel any pain when I read it. We must write in a way that strips things down, and write in animated specificity, so our writings can pain our hearts.

B: One central plot in Lee Chang-dong’s film Poetry can almost serve as a model for this. A grandmother attends a poetry class, where the teacher advises the students to observe things truthfully. This is similar to the preparation art-school teachers demand, before one makes a drawing or any other visual work—this “thing” that you talk about, is composed of what other “things”?

As the granny learns to write poetry, her memory deteriorates, but it deteriorates into an apparent pattern—she could only remember what a thing is, but not what it’s called. Therefore, when she talks about a thing to other people, she has to describe it in painstaking detail. This is kind of like what we’ve been doing.

C: Yes! I’ve been getting recommendations of Poetry from friends, but I unfortunately haven’t watched it. Our excitement and sensitivity towards words aren’t a passive act of resistance, but it’s interesting how the granny’s dissections of words are in direct relation to the body and to time. How to explain “solitude” to a kid? How to talk to my grandma about the subtle undertone of “qià fàn”, in which accepting video sponsorships is synonymous with a necessity for survival? This isn’t purely for an indulgence in the play of semantics (although, on the temporal-epistemological axis, languages do burst and collide), but out of a necessity to understand and communicate.

It reminded me of when I first read an English-to-English dictionary, where an unfamiliar word is explained through other similarly unfamiliar words. More and more alien vocabularies are introduced so as to arrive at a more accurate description. But for English-to-Chinese dictionaries, can languages truly fit together like perfectly manufactured gears? What type of experience is common? What kind of red do you see when you see the words, “a red rose”?

I wonder whether language has been burdened with too much of a sense of mission and responsibility, which might partly explain people’s adoptions of different languages and voice (the bullet-proof rigidity in contracts, the self-perfecting hollowness in critical writings, the flattened emotions in conversations with foreigners), in hope of matching the different expectations set up.

D: There are definitely a lot of recent moments that make me think of dictionaries. I’ve thought about making a dictionary that radiates outwards, where one word will link to another word, then other words. But it will be extremely personal—your dictionary must be fundamentally different to mine. How do you decide if a word is connected to another? How is that connection established? How to describe these connections?

A: I recalled reading the Wikipedia guidelines, which have notability as one of its criteria to decide if a person deserves an entry. The criteria for actors’ notability are outlined in detail, defining “important supporting roles” as “roles who share the leading roles’ parts and have close interactions with them; nominations for best supporting actors/actresses at various awards ceremonies can be used as a reference to decide the weight of the role (as in their parts in the work, not in their acting skills).”

The myriad of Wikipedia links in one entry will point to and land on another entry that is hundreds of web pages apart. It can go on and on forever. Aren’t we chatting in the same way? As a kid, I loved fooling around and talking with my parents before bed, tracing the origins of our conversations. This backward search would bring me a sense of reassurance and a sound night of sleep. Like the baby in Milan Kundera’s novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being, drifting down the stream in a boat while clinging onto nothing.

D: I feel like certain works can only be made with someone else’s pushing hands. Has it ever occurred to you?

What is pushed includes collaborations, inspirations, and of course, certain negative things.

A: Haha, I think I’m usually the pushing hands for others. “Push” generates a two-way force that acts upon others and me alike. In fact, many words of encouragement also apply to me, however in most cases, because I know too much about myself, or I am being sensitive, it is hard to take in those pushing forces easily.

D: Yep. I’m imagining scenarios where making work is complementary and reciprocal, where one reminds another, one unconsciously guides another, one inspires others without knowing it, one is inspired without knowing it. (over)

A: Too many ones, too alone… this reminds me of Yoga Lin’s I Always Practice Alone (saying “over” here is kinda like talking to oneself… over)

D: It’s just as nice to be in the state we’re in right now. A simple, aimless chat can nevertheless lead me to interesting ideas I’d like to delve deep in.

A: Exactly. Sometimes I feel like you talk in such a serious manner, and sometimes my responses are equally serious, but then there are times when I’m like, oh well, I’ll just let this one slide. There is a laid-backness to our conversations, where we don’t have to walk on thin ice all the time.

D: In high school, I once participated in the opening show for an art festival, where I was asked to recite and perform the poem Invitation to Wine. The forty or so minutes before my performance, I was so stressed that I almost passed out. The only comparable feeling was back in middle school, when I saw the girl I had a crush on walk towards me. However, my performance was pushed back for some reason. And by the time I eventually stepped onto the stage, I was already too numb to feel anything, and therefore finished the poem like nothing ever happened. But that tightened sense of nervousness returned immediately after the curtain call. Similar incidents recurred in all my later performances, almost with no exception.

A: The nervousness intensifies as you wait. If it were the case with your middle school crush, it’d be her walking in slow-motion for forty minutes… An elongated tension, like how a ball of dough is being stretched. (I am in a particularly relaxed state and would love to crack a joke or two.)

D: Did I ever mention why I’m a little hunchbacked?

A: I never really noticed (that you’re hunchbacked). But I remember how—I’m not exaggerating—your eyes lit up when I tried to talk you into dancing and mentioned posture corrections.

D: There’s more to that. Well, I’ve been a tall kid growing up, but I didn’t always get assigned the back seat in the classroom. But I didn’t want to block my classmates sitting behind me, and I would bend down. Bending yourself down makes you more approachable in general. My hunchback is therefore a personal choice.

A: That’s so sweet of you. I paid a recent visit to my high-school Chinese teacher, whose students all agreed that I look just like one of their classmates (I stared at that boy and thought, no way. But I kind of knew why they thought so). It was someone with particularly narrow shoulders, hands tensely resting in the front, which flattens his body. I almost told him to straighten up his back, but it’d sound so rude and patriarchal — in the end, I remained silent. Who am I to judge and decide others’ postures? If someone told my high-school self to straighten up, I’d most definitely complain: I don’t need you to tell me that! Yet without muscle and balance training, even if the body is temporarily opened up, it would quickly snap back into its normal state due to discomfort.

D: As for my excitement for posture correction, it has to do with something odd I noticed during my performances. When I perform, I find myself walking and moving differently from how I normally walk and move, as if I conjured up an alternative body coordination system. Then I thought of the possibility of developing and expanding my “neutral” personality, through more performances with specific settings.

A: I’ve noticed before, that foreigners tend to speak Chinese in rather high pitches. I later realized, it was because the accompanying audios for their textbooks are read by female voices, which led them to believe that the high pitches are a part of the language.

D: Never thought what comes to mind first would be a (foreign?) poem that I meticulously studied. From experience, one needs to reference translations in different languages to understand a poem.

Having said all these, I realized how, as an individual, I’m in the initial stage of self-awakening, where I am only learning to confront myself with all honesty and sincerity, unable to offer more in-depth advice or insights for others. At least in this case.

What has come out of this conversation is that I must hold onto my sincerity. If wisdom is lacking, then remain as sincere as possible. Well, this is a sudden but sincere moment of epiphany.

A: However cheesy, as long as it’s sincere, I’ll never get tired of it. Like how I am never tired of those corny rom-coms.

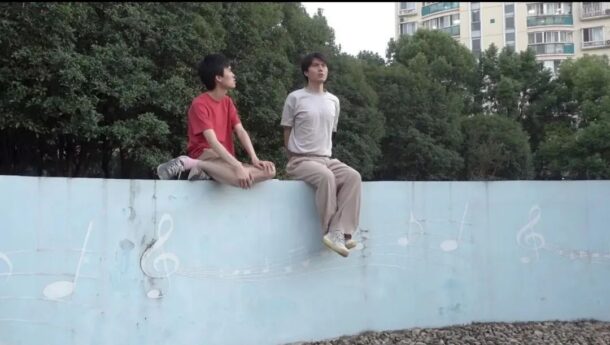

Amiko Li doesn’t come from a writing background, and therefore prefers to play, explore, and learn with words without any baggage. He is currently thinking about language and voice through vocal training.

Dong Longyue has been in Shanghai for one year and two months. His work often arrives at the verbal. He’s been warming up for exiting the word game, but often gets too warm and can’t withdraw entirely. Lately he is a person who is always about others.

Translated BY Sixing Xu

Dong Longyue

Dong Longyue