THE 4TH ATHENS BIENNALE: AGORA

| February 25, 2014 | Post In LEAP 24

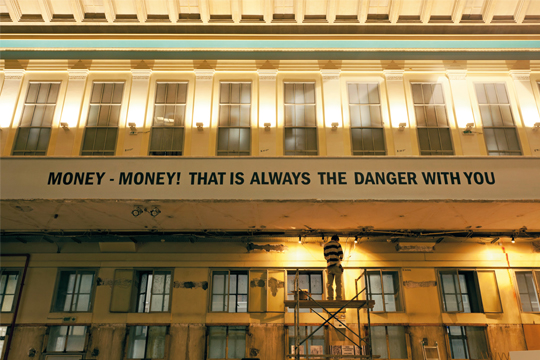

Vinyl, 10 x 490 cm

PHOTO: Mariana Bisti

Courtesy of The

Apartment

This year, red and black flags were raised outside the main site of the 4th Athens Biennale (AB4): the former Athens Stock Exchange building, which closed its doors in 2007. The colors invoked associations with fascism and anarchy, two things that have arisen out of Greece in its eight years of social, political, and economic crisis. The use of these loaded colors underlined AB4’s provocation: to put the zeitgeist’s money where its mouth is and attempt—in practice—a biennial exhibition that engaged with the “anarchic” idea of collectivity. It started with an open call, placed only six months before the biennale opened, for not one curator but many. In all, around 40 curators, artists, theorists, and practitioners in the creative industries worked on the project, including Charles Esche, Brian Holmes, Galini Notti, Christopher Marinos and Athens Biennale co-founders Xenia Kalpatsoglou and Poka Yio.

Aside from the notion of the singular curator, AB4 also rejected the idea of a static showcasing of artworks with a parallel program of events. Objects, of course, were shown, in the form of some 100 artworks spanning painting to video. But not 70 or so participating artists presented artworks, nor were they “artists.” Projects, workshops, and happenings formed a large chunk of AB4’s exhibition list, in many ways forming AB4’s core. From social scientists to political theorists, many participants were invited to share perspectives on the current crisis of neoliberalism from their areas of expertise, with ample online documentation and live streaming. The ultimate aim: to produce encounters not between art and the art market, but art and the economy.

In this context, the Old Stock Exchange was an effective conceptual frame for AB4’s title: “Agora,” which interprets the marketplace as a space of social, monetary, and political exchange. AB4’s weekly happenings included a project by Jenny Marketou, a performance-lecture and workshop by Tania Bruguera and a performative, multi-media installation by collective FYTA. A majority of these unfolded in the main trading space of the Old Athens Stock Exchange underneath George Harvalias’ ingenious re-installation of the actual Athens Stock Exchange price board depicting the markets on June 26, 2007, when the Stock Exchange held its last session. The space also hosted the 4th Athens Biennale’s Economic Conference (coordinated by David Adler), focused on the question “What Now?”—a belated but nevertheless important question considering the 2008 global economic crash and its ramifications.

With this in mind, a text intervention produced by Dimitris Dokatzis throughout the building rang especially true: “The Troubles of the Future Soon Faded Before the Troubles of the Present.” In Greece, where society’s infrastructures are collapsing against the pressures of the economy, there is a dire need for alternative political solutions for the country’s economic troubles. Artworks contributed and expanded on this, with a specific grouping resonating with the social movements that have arisen worldwide since the 2011 Arab uprisings. Gabriel Kuri’s Quick Standards (2005) tapes four emergency blankets onto wooden sticks to invoke protest signage. Sam Durant’s La Plus Belle Sculpture (2007) quotes a slogan from the May ’68 movement in graffiti on a mirror, “the most beautiful sculpture is a paving stone thrown at a cop’s head.” Meanwhile, Aspa Stassinopoulou’s 1977 work Read presents an excerpt from Peter Schneider’s 1969 essay “Die Phantasie im Spatkapitalismus und die Kulturrevolution” on 19 pieces of wood, stating a need for art to “build roads that will serve the exchange of human desires and distinctions,” not “the circulation of commodities.”

Of course, one could criticize such proposals as contrived within the context of a biennial exhibition—such was the fate of the 7th Berlin Biennale, judged by many to have capitalized on the Occupy Movement. Yet, whether a biennial might prove effective as a platform to discuss, debate, or even produce new forms of political practice remains to be seen. Nevertheless, responding to the urgency of the present moment, AB4 took the risk and transformed itself into a site of discourse, asking questions similar to those raised in Irina Botea’s video documentation of the performance Photocopy/Fotocopia, itself a product of the June 2011 Barcelona protests. In the work, Botea explored spoken words and gestures through techniques appropriated from The Theatre of the Oppressed. In doing so, the artist asked, quoting AB4 curator Glykeria Stathopoulou, “how spontaneous public protest can be transformed into a sustainable process of participatory democracy”—essentially one of the key debates of our times.

Installation, dimensions variable

Courtesy of the artist

As for the answer to the question “Now What?”, Chrysanthi Koumianaki’s designs for a future currency in The Economy is Wounded (2013), pointed to an answer. In the work, Koumianaki’s research proofs and various banknote designs (the final object is not shown) underscored the notion that money is a representation, a creative production, and essentially an illusion. This reality was furthered in the visual references Koumianaki made in her futurist banknote designs to Étienne-Louis Boullée’s “Cenotaph for Newton” and Claude-Nicolas Ledoux’s “Ideal City”—both unrealized utopian architectural proposals. If money and even cities are born of mere imagination, then other realities are indeed possible, should we wish to design them.

But there are obstacles to making brave new worlds, alluded to in two text works presented in the Old Stock Exchange’s trading space: Dimitris Dokatzis’s “Money – Money! That is Always the Danger With You” and Thomas Poulsen’s neon sign Tzatiki (2005), which reads: “Your Success is Your Amnesia.” The two pieces point to a collective inability to imagine different futures out of a fear of letting go of a construct—or illusion—that ironically supports and unites us today: capitalism.

This is where Theo Prodromidis’ contribution to AB4 comes in, in the form of his four-channel video installation Towards the Production of Dialogues on the Market of Bronze and Other Precious Materials (2013), partly filmed in the Old Stock Exchange. The work references Bertolt Brecht’s The Messingkauf Dialogues (1939) (Messingkauf meaning “Buying Brass”), which debated the place of art in society while proposing a new and radical form of theater connected to social realities. Prodromidis re-imagines the discussions between five characters: a philosopher, actor, actress, electrician, and dramaturge. In his script, Prodromidis mixed Brecht’s observations that, “It is impossible for singular individualities to meet in an event without a revolt, a reconnection of an action and an encounter, either political or emotional,” with lines from Anne Clarke’s 1983 song “Our Darkness:” “there were too many defenses between us, doubting the time, fearing the time.” This inter-lapping highlighted the main obstacle to true and effective collectivity: the individual’s reluctance to participate in the group.

In many ways, Prodromidis’ take on Brecht summarizes the proposals made throughout “Agora.” The film ends with the conclusion that art lost part of itself when it was taken on to promote “the new business” while remaining “the old art.” As the doors to the Old Athens Stock Exchange come into view, it is stated that only by giving itself up did art win itself back again. Using these terms, the 4th Athens Biennale indeed gave up. It relinquished the presentation methods of “old art” within the space of the “new business” art has helped promote: the capitalist marketplace. But then, it transformed this marketplace into a transdisciplinary site of political and social potential, making it, by definition, an agora.