YU BOGONG: CROSSING THE RIVERBED

| April 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 2

Compared to the works on view in Yu Bogong’s 2007 show “Karma” at China Art Archives & Warehouse, those of his recent outing “Crossing the Riverbed” at Beijing’s Magician Space assume more complex forms. Yu has always been engaged in exploring connections between the internal spiritual world and religion, historical memory, psychoanalysis and cultural symbols. This exhibition confirmed what was previously a nascent move in this direction.

Yu Bogong started to create soft sculptures out of silk in 1996 with pieces like Shoes, Life Buoy and Graduated Shit (2006). These beautiful silken materials did not exude the reserved Eastern reticence that people often imagine; instead a sustained tension lies sewn between the quality of the materials and the objects they form. A suggestion of religious ceremony peeks out from the works’ humor to leave a lasting impression. In “Karma,” Yu started to shift toward installation and sculpture with pieces such as Sound Box of Herbal Medicine, The Blackboard (The Mandalt Community), Inner Strength and The Body (2006). Some of these memory-related pieces are dislocated in space and time: The Body, according to Yu, “tries to portray the conflict between one’s ambition and reality in a surreal manner.” In this show, a convincing grouping of recent and new works expands the scope of Yu’s explorations to broader territory, with some works even forming an entire motor and symbolic system. Differing from other artists’ formal substitutions of three dimensions for two or the complex for the simple, every change in the appearance of Yu’s work seems to grow from a deepening of his investigation into the nature of the human spirit, stimulating intelligence and elevating the spiritual world.

Two pieces chosen for this show are recent focused explorations of the question of “sublimation and individuation,” described Carl Jung as the process of transcending the mutual repulsion of opposites to strive for their integration. In his work Yu Bogong attempts to realize an invisible and at times concealed inner world, but one that can still be felt. This process resembles a sort of anti-Copernican revolution, or the gradual Taoist practice of “internal alchemy” (nei dan).

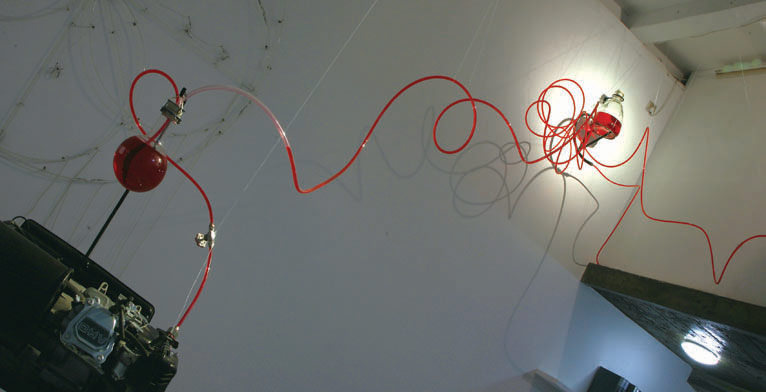

In the main hall, To the Origin uses an integrated system of symbols in an attempt to construct an individual inner world. Three sets of neon lights resemble a heavy curtain, blocking out the world the viewer wishes to enter. Revealed at one corner of this curtain is a red liquid flowing through a tube suspended in midair, an engine connected to a pump roaring and shaking like a cornered animal and a round beaker in the middle reflecting light onto the artist’s mandalas, hung on the surrounding walls. Truth lies among these objects in a dynamic that in science might be called a process of conjecture, hypothesis and proof, finally concluding in an inevitable causal relationship. The artist can bring into play any kind of form, place it in a specially designated environment and, before any explanation of it forms, use one or several metaphors to declare its nature and thereby allow it to cast off the limits of time, space and fixed modes of thinking. Here metaphors allow the visual imagination to make its own connections in a four-dimensional world. There are at least three parts to the piece. The red oil (blood) serves as a metaphor for life and industrial society’s source of power; the energy released by the reworked generator when it is turned on (it also provides power for the entire gallery’s electrical system) is a metaphor for the Big Bang, evolution and the driving force of social progress. The mandalas the artist has designed express—on the level of individual consciousness—a person gradually transformed from a natural state to one of completeness inside and out. On the level of natural evolution, the mandalas stage a progression from cosmic origins to the boundless universe— subconscious, shadows, culture, society and religion—a passage through the Eight Consciousnesses as revealed to different individuals resulting in final purification as a butterfly. The piece introduces the Octave Principle in the evolutionary process as interlinked with the purpose of the round mandalas, creating an internal connection to present the complete process, as described by Yu, of “a) expression of the abstraction of time and space in primitive religion, b) holistic inner-self perception and c) the only way to achieve an absolute self.”

The end form of the materials used in the work creates a field that expands and connects with their original state. The materials composing the work are not of the real world, but rather lie between it and a subconscious world of the imagination. The artist requires material symbols to help him to establish a defined relationship between himself and the unspoken object. As this system gradually arcs toward perfection, it forms an integrated field, and an absolute world finally emerges from the many relative ones.

Transformation, another work on display, presents a more explicit description of this absolute world. The artist uses a molted cicada skin to present the process of individuation, the cycle of life through space and time. Cicada nymphs, living underground, shed their skin four times over two to three years of growth before surfacing, going through the pupal stage, and emerging with their wings before they re-enter the shadow world (an adult cicada only lives for sixty to seventy days). While the cicada’s lifespan is very short, its spirit cycles back and forth. When the cicada skin on the gallery’s wall breaks open in a puff of white smoke, the world quiets for a moment; this is an integrated journey, a path toward individuation, that attempts to separate us from prior cultural experience (or inertia) and indigenized traditional experience.

Yu Bogong’s creative method usually begins with reflection as he determines the nucleus of a work through deep probing, followed by repeated adjustments and finally resulting in a scheme for the work’s execution. Besides drawing from his own memories and practical experiences, Yu does not simply assemble the knowledge (symbols) used in his work but diffuses them outward, attempting to bring about a transcendent scheme for spiritual awakening. Borrowing from knowledge systems across disciplines and fields and remolding them through subjective perception, this approach is not as straightforward as Western thought patterns and might at first create some distance between the viewer and the piece. But this false perception into which people are initially drawn is in fact an equal interaction between the artist, viewer and the work, a mysterious territory, which Yu doggedly pursues.

Since the Enlightenment, people have become accustomed to classifying knowledge. The well-worn path of discovery, research, acceptance, and incorporation into existing paradigms has become a basic epistemological pattern, developed in the West but later adapted to cultures and contexts elsewhere. And yet we increasingly see how the complexity of the real world has caused empiricists to lose their bearings, sensual perception, and ultimately their ability to systematically analyze and carefully predict. When interpreting problems within single branches of learning becomes strained from lack of evidence, an Eastern sensibility born of “combining” promptly restates its worth. “Crossing the Riverbed” can be seen as a re-evaluation of this worth. Guo Fang