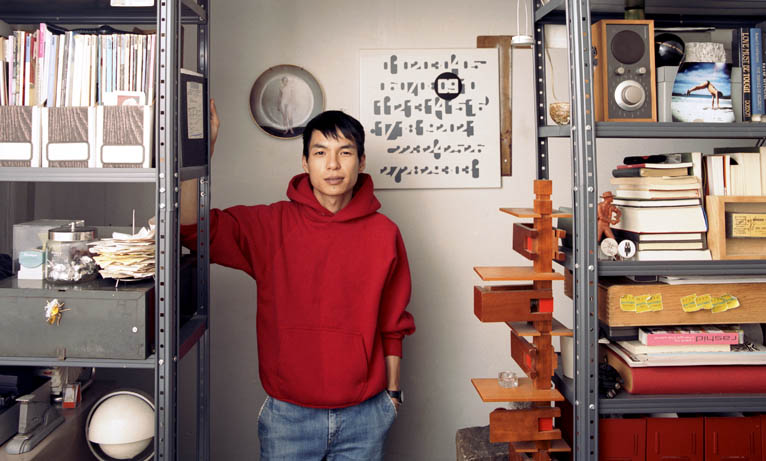

TOBIAS WONG: TOOLS FOR MODERN LIVING

| October 3, 2010 | Post In LEAP 5

It’s best to get the fact that Tobias Wong died on Sunday, May 30th of this year out of the way immediately. He was 35. Wong’s burgeoning career began as a precociously incisive graduate student at Cooper Union when he ganked a new armchair from no less a design luminary than Philippe Starck. He turned the chair into a lamp (This is a Lamp, 2001) and showed the composite piece a day before Starck’s own official US debut. From that prank on, Wong’s work and life came under the spotlight as a rising star of the design world. The designer’s vicious work, punk objects that mingle conceptual sculpture and product design, play at providing the proper equipment for living a contemporary life. Part of a young scene and part critic of the same, Wong left the world with a breadcrumb trail of functional objects that lead a crooked path between the unique and the everyday, luxury goods and accessories to petty crimes, real life and a fetishization thereof. Sometimes cynical, sarcastic jokes, at other junctures hopeful, optimistic, and beautiful, Wong’s objects are the perfect tools for dissembling in the age of mechanical deconstruction.

Tobias Wong, known to everyone he knew and many he didn’t as Tobi, fought against what he saw as toothless contemporary design—glossy replays of high Modernism and Minimalism, the Ikeafication of pretty much everything— with his own attacks of cheeky appropriation and détournement. Wong targeted irrelevance with irreverence, fighting the idea that “Design” is somehow meant to transcend our everyday lives and present an unreachable ideal of gesamtkunstwerk living rooms in monochrome. Though Wong’s work has often been cited as part of a genre of “conceptual design,” characterized by the use of design as critique as well as function, he designated himself “para-conceptual.” The term, according to the artist’s website (not updated for the past 846 days, a digital epitaph), signifies works “of, relating to, or being partially conceptual. (no longer having to be just purely that).” Wong wasn’t interested in beauty for beauty’s sake or conceptual critique for critique’s sake; rather, his work sought to mingle the two, using the visual to critique the conceptual, and the conceptual to augment the visual.

The objects Tobi has left us solve a few problems fundamental to modern life. Among the most popular of his products are Smoking Mittens (2003), a pair of ski glove-like hand coverings that come with a unique feature: between the index finger and the middle finger, a hole is punched and riveted. The purpose: to poke a cigarette through while wearing, the better to smoke outside during the winter months. The gesture, a piece of functional design for the masses, has a clear tongue-in-cheek edge. Do we need another machine to help us suffer from our vices? The cynical interpretation is a critique of human excess. But if you’re that cynic, do you really want to freeze your hands off just because you have to leave a bar to smoke in December? Wong’s answer reacts to a physical problem even as it assuages an abstract exclusionary guilt. It’s a fix as American as a beer cozy: consumption can solve anything. Wong himself smoked Marlboro Reds, by the way.

Luxury goods presented fitting targets for Tobi’s barbs. People carry name-brand bags or sport jewel-encrusted iPad cases to convey wealth and status. Really, though, wouldn’t it be a better trophy to be able to cut out the middleman and simply shit gold? How many members of the elite can claim that? Wong’s Pills (1998), in both gold and silver flavors, will decorate your excrement with flakes of pure precious metal. Disposable Lighter (2003) is lined with mink fur, the high and low mingled in something you chuck after a few packs. The designer once curated a design shop in which the goods on sale could be gift-wrapped in real live Andy Warhol screenprints. Wong took an iconoclastic joy in the culture of a city and a country and a planet endlessly hungering for an infinite parade of consumable crap. In the avalanche of baubles and plastic knickknacks and shiny electronics that form the majority of our lived experiences with design, his objects stand out like thorned roses, consumable goods that through consumption, critique it. And yet Tobias Wong never lost the humility and humor it takes to admit that in the end, we all love stuff we can buy.