BREAK IT DOWN, BUILD IT UP

| September 7, 2011 | Post In LEAP 10

Launched in 1994, Pots was Taiwan’s original alt-weekly. Aside from a brief hiatus in 1997, it has been publishing now for over 15 years, with a mandate to “break taboos and remove barriers,” reporting on a wide range of controversial social and cultural topics.

AT ITS FOUNDING, Pots Weekly was originally introduced as the Sunday supplement of Taiwan Lihpao Daily, a feisty daily founded by Cheng She-Wo in 1988. When Pots went standalone in 1995, its funding and facilities came in the form of interest-free loans from Shi Hsin University, a college Cheng had founded. Free of economic pressure, the weekly was able to develop a unique voice. In his editorial for the inaugural issue, editor-in-chief Huang Sun-Quan wrote: “The creation of Lihpao reflected the understanding that a generation neared liberty yet remained fractured. Lihpao intended to build a space that embraces divergent voices, to imagine an outline for the society’s future. And now Lihpao introduces Pots Weekly, a labor of love more than one year in the making. In this act of creation, Lihpao is attempting to cut off any connection to the previous generation; it seeks to continuously destroy every and all taboos.” Break taboos, remove barriers and assert a firm stance, thus was the spirit Pots’ founders wanted to uphold.

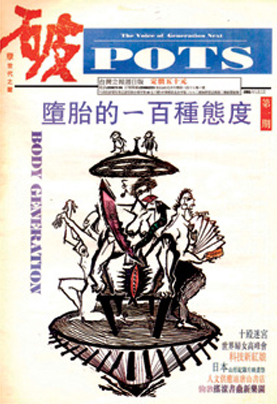

The inaugural issue was themed “One Hundred Attitudes About Abortion.” The articles covered a variety of views, including interview transcripts and accounts written by women describing their experiences with abortion. The “Complete Guide to Abortions” demystified the process of an abortion, bringing to light the unseen procedures rarely spoken of. Western-trained doctors explained the medical aspects, while traditional Chinese doctors offered prescriptions for nourishing tonics to aid in recovery. The all-embracing coverage also extended advice on how to avoid an unwanted pregnancy, written in clear, everyday language. The article “Woman’s Body, Patriarchy’s Battlefield” illuminated why access to legal, safe and inexpensive abortions was the foremost demand of the women’s movement.

Gender issues, women’s rights, sex workers’ rights, gay identity and culture, social movements, student movement, youth culture, contemporary art, underground music, rave culture, and drugs are all points of interest in Pots’ world. But the Pots verion of the counterculture was as much about establishing new ideas as breaking down old ones. Nearly every member of the editorial team had either been involved in the student movement of the 1980s, or was an underground cultural impresario. They invited their friends to contribute articles, turning the weekly into an organized powerhouse.

The editorial process of Pots is by design open to all members of the team. From editor-in-chief to advertising staff to delivery boys, every employee was invited to express their opinion as to whether a story is relevant. The reporter must convince the editor that a topic is worthwhile before conducting interviews and beginning research. “We have some established guidelines,” says Huang. “We want to ensure that every contributor’s articles have their own style, view point and way of speaking. This in turn means that every generation of Pots staff creates different content. At the same time, any news item must be considered from perspectives of gender, class, animal rights and age. The questions that we ask are: Who is in favor? Who is against? Who benefits? Who loses?”

Then in 1997 Pots halted publication citing economic reasons. When it resumed, Huang Sun-Quan followed the free circulation/paid subscription model of the Village Voice, and added more events listings. Distribution also expanded into college campuses, coffeehouses, music venues, and even the Taipei Metro system. In the meantime, Pots’ circulation has risen from 3,000 copies to 80,000 copies.

In 1997, at the time Pots ceased publication, Huang penned a “farewell editorial” that said in part: “Every mainstream was once an alternative, and any alternative might become a mainstream. If Pots has failed, it is because we did not establish our indispensability in the conversation between these two extremes.” Asked recently whether Pots has now engendered this indispensability, Huang replies, “for a publication that brands itself as alternative, the goal is not to survive but to have something to say. Maybe one day we will have nothing more to say, then at that time I might cease publishing Pots.”

QUEER CULTURE IN TAIWAN

HUANG SUN-QUAN ON POTS AND ITS GAY-RIGHTS LEGACY

I remember when we first began to tread his path, equipped with only the most simplistic ideal of political correctness: just as middle class women fought for womens’ rights and changed perceptions of gender, we argued that “queer” should be considered an equally important cultural distinction. Since at that time the media paid absolutely no attention, we started to write about queer culture. Queer studies had just begun to be taken up in Taiwanese academia, albeit minimally: we actually helped provide much of the fieldwork for academic projects.

At that time the mainstream media weren’t willing to discuss anything, and we received warning letters from the bureau of information on account of certain reports. Even though martial law in Taiwan had ended many years prior, many still considered homosexuality inconceivable. We had made it into the Taipei Metro and could be found at any train station, but on account of too much gay content, the subway company terminated its contract with us, citing our “adverse influence on young peoples’ physical and mental health, and damage to the image of Taipei Metro.” At that time there was no annual gay pride march; the community operated underground, staging screenings, readings and talks. Nowadays we’re frequently praised as the gay newspaper.

I wanted queer culture to be at the forefront of Taiwan’s other subcultures. A few important novels came out around that time, particularly Chiu Miao-chin’s Montmartre Suicide Note. We all ignored the fact that the reality depicted in the novels and films didn’t quite correspond to our own; at that point Taipei already had several very well-known gay bars, the gay scene was closely tied to electronic music, with the bars Funky and Texsound for example.

It’s hard for me to give an objective evaluation, but from another perspective, when I receive warning letters from the government, or phone calls from parents saying that our newspaper is damaging their children, it drives me all the more to continue doing what we do. If we cannot speak up for the voiceless, then what is the point of working in the media? At its best, Pots has been at the forefront of the subculture, opening up spaces that did not exist before.

I sometimes ask myself why now, after over 20 years, we still have to deal with certain Taiwanese religious organizations— such as “Jesus doesn’t love Homosexuals” or “True Love Alliance”— who are against the inclusion of homosexual issues in primary and secondary school education. The beliefs of these organizations show that we haven’t done enough, that we can’t have influenced people that much.

Translated from Chinese / Translation: Liu Jiajing, Dominik Salter Dvorak