ATSUKO TANAKA: THE ART OF CONNECTING

| June 27, 2012 | Post In LEAP 15

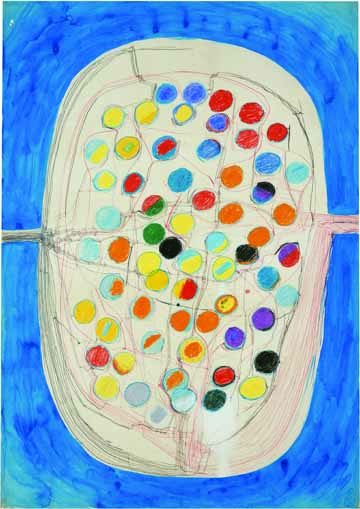

Following a performance of the now iconic Gutai work Electric Dress (1956), Atsuko Tanaka laid down the garment’s 200 colored light bulbs to rest on a piece of fabric. Still hot, the light bulbs scorched the material, leaving behind an ad hoc composition of black circles loosely marking out a figure. This figurative index, both abstract and diagrammatic, marks the transition from Tanaka’s early multi-medial experiments to the large poured paintings that became the sole focus of her work from 1958 until her death in 2005. These two phases are so marked that visitors who passed briskly through “Atsuko Tanaka: The Art of Connecting” at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo (MOT) could be forgiven for thinking that they had encountered two different exhibitions by two different Tanakas. The first, a furiously inventive avant-garde spirit whose 1950s trajectory across media traces a tour-de-force of experimentation; and the second, a highly idiosyncratic abstract painter whose colorful circle-and-line motif modified incrementally over a period of decades.

Through the transitional work of Electric Dress an indexicality to the figure, or to the body, can be found as a shared concern among these two strands of practice. It is also this foundational connection with the figure that makes Tanaka’s work so deeply complicating to the story of Gutai, which in its gestural automatism avowedly rejected any figural depiction. The striking diversity and enduring originality of the works within the recent Tokyo exhibition also present an oeuvre that is more generally unsettling to Western art-historical narratives of precedent. Like an electric flash, Tanaka’s work from 1953 to 1958 skirts across minimalism, materially-inflected conceptualism and intermedia strategies, often a full decade before such movements would be hailed in Europe and the United States.

The exhibition at MOT stands as the final presentation of this touring retrospective, with showings already held at Birmingham’s IKON Gallery and the Espai d’art Contemporani de Castelló in Spain. Within this international frame, the show lines up as one of a set of solo surveys that, over the past year, have excavated the work of significant women artists who are marginal to the Euramerisphere. Sanja Ivekov, Nasreen Mohamedi, Lygia Pape, and Alina Szapocznikow have all been subjects of retrospective showings that exposed practices that have, in turn, complicated canonical art-historical accounts. The Tokyo presentation of “The Art of Connecting” is the most extensive of the three editions, drawing upon numerous local collections to assemble a display of over 100 drawings, sculptures, garments, technical diagrams, prototypes, collages, and above all, paintings. From her first collage experiments in 1953, Tanaka considered all of her work, regardless of medium, to be “painting.”

While it is a paint-on-canvas piece that adorns the MOT’s posters for the event, it is undoubtedly Electric Dress that is the most widely known of Tanaka’s work, particularly since its inclusion in the 2007 Documenta 12. Within “The Art of Connecting,” Electric Dress shares a room with a work equally worthy of such attention, if perhaps less strikingly photogenic, Work (Bell) (1955). The piece starts as a press-button which, when held down, triggers a series of twenty alarms to go off in two-meter intervals. At MOT, the line of alarms traced the border of the room containing Electric Dress and then trailed off around a corner into a room of paintings before making its return. Producing a truly spine-rattling sound, Work (Bell) indelibly imprints on the visitor an experience of the body in connection with space and time, as well as the contiguous edges of contact among the three.

Also on display are the plans and prototype for the novel “notch” device developed by Tanaka in order to make the two-second delay among the alarms technically possible. Here, the depth of Tanaka’s inventiveness, literally as an “inventor,” is readily apparent. An essay in the accompanying catalogue by Gutai scholar Mizuho Kato details the compelling story of the work’s development, and its signal place within her oeuvre.

Inventor, electrical engineer, sculptor, collagist, proto-minimalist, experimental maximalist, performance artist avant la lettre, and abstract painter; it is remarkable that one artist’s practice can meld so many permutations coherently together. Indeed, it is as an avant-garde seamstress that Tanaka first appears in the MOT exhibition, via footage of her performative work Stage Clothes. In barely-surviving film fragments, Tanaka is captured unraveling layers of specially designed clothes during Gutai “Art on Stage” exhibitions in 1956 and 1957. In a spiral movement her dress peels off like an orange-peel; from the sleeves of a garment long strips of fabric unravel, wrapping her body and fastening to form a tunic; the hem of one dress contains the beginnings of the next.

The mesmerizing and rhythmic transformations of Stage Clothes constitute the first of three film screenings within “The Art of Connecting” that punctuate the exhibition. They mark its beginning, middle, and end, each time foregrounding the bodily within Tanaka’s work. The second film, Round on Sand (1968), features a work inseparable from its outdoors location. The 16mm film looks down from a high angle as Tanaka applies her circle-and-line idiom to the firm sand of a beach on Awaji Island. A beach-long composition is created as Tanaka drags an ice-axe in varying radii around her body, joining them together with lines made by walking between. Encroaching on the vivid grain of the everyday, this unexpected and candid piece is a highlight of the show.

The third film, Tanaka’s Round Circle (1966), occupies the final room of “The Art of Connecting” and similarly aligns Tanaka’s painting with her body, albeit in an even more direct fashion. Its fixed shot features a slowly rotating circular canvas set against the unlikely lush-green garden background of the temple where Tanaka and her husband, fellow artist Akira Kanayama, lived following their tumultuous 1965 break from the Gutai group. As the tangled circles and lines of the painting slowly, hypnotically spin, Tanaka walks into the frame, stops in front of the painting, spreads her arms and then walks off. After a moment she re-enters, crouches, stands, and again walks off. Such callisthenic exercises continue intermittently, marking the painting in direct relation to the physical proportions of Tanaka’s body as a kind of comparative anatomy.

The notion that abstract painting could be indexical to the figure flew right in the face of Gutai’s concrete materialist doctrines. Scholars of Gutai, such as Kato, have noted the halting difficulty that Gutai leader Jiro Yoshihara had in accounting for the figurative quality in her work, describing her as a “special case” on the occasion of the 2nd Outdoor Gutai exhibition in 1956. Of course, it was not only this figurative inclination that made Tanaka “special” within the context of Gutai, but also her gender. With “The Art of Connecting,” MOT took the opportunity to highlight a half-dozen lesser-known women of the Japanese avant-garde. Hideko Fukushima, of the Experimental Workshop (Jikken Kobo), bears notable comparison in her work as costumière for several of the group’s stage performances.

When focusing solely on the work of Tanaka, “The Art of Connecting” allows the internal themes and concerns of her work to emerge with singular clarity: the figure and its conjoined borders, the vibrating surface, the perpetual bodily presence. How these play out in direct relation to other artists’ output of the time is not broached directly, nor is the possibility of a latent feminism or woman-centered inflection within the work. However, with a series of Gutai exhibitions forthcoming across a veritable who’s who of major Western museums— including MoMA, the Moderna Museet, MOCA, and the Guggenheim— this will be a fascinating trajectory to follow. Vivian Ziherl