DUAN JIANYU: ATTACHING REALITY TO SURFACE

| May 10, 2013 | Post In LEAP 19

THE NARRATIVES OF Duan Jianyu’s paintings tend to start out with everyday reality, and then midway through fade out and slip slowly into the world of the mind. This kind of narrative technique appears consistently in the artist’s creations. Take for instance the fictional text of New York, Paris, Zhumadian (2008), inspired by a piece of news at the time about a rural university student who took his sick father with him to school. Duan Jianyu pens the name “Jiao Huxiang” for the boy, evoking the image of a simple youth who is honest, kind, and slightly slow of speech. Huxiang’s crippled father is optimistic and clever, endowed with the expressive abilities of a true xiangsheng performer. Duan Jianyu describes the scene in which Huxiang brings his father to the school dormitory:

“Because he lay on the bed for so long, unable to move, Huxiang’s father’s body was prone to bedsores, and he needed to be turned over constantly and washed. Huxiang took thoughtful care of his father, and often between his second and third class would hurry back to the dormitory to turn him over. But the most difficult thing to master was the irregularity with which his father would relieve himself; just when Huxiang thought all was clear, his father would go all over the bed.” Observing the pairing of such physiologically vivid descriptions with such consummate displays of filial piety, one cannot help but think of The Twenty-four Filial Exemplars, a quintessential textual embodiment of the Confucian spirit in which one dutiful son, in order to accurately diagnose his father’s illness, tastes his stool to judge its flavor; while another cleans his mother’s bedpan, attending to her day in and day out. Much like elsewhere in Duan Jianyu’s works, where she employs parody, allegory, ridicule, and a variety of other techniques to reference such elements of local tradition, using plum blossoms, orchids, bamboo, and chrysanthemum, peasant women and amateur art enthusiasts seeking entry into the Chinese Artists’ Association, the story of the filial Huxiang shows us again the bottom line in Jianyu’s narratives. She begins with a “low” form of reality, something like popular or “low” culture, and edges upwards, one inch at a time, ever higher into the heights of her own narrative attic. It can be said that reality constitutes the base coating of her narrative paintings, and that this hue, despite its fade into the background, despite its eternal lack of depth, is still the very factor which determines the style and method behind her painting.

Huxiang’s story is a text with the experimental spirit of the nouveau roman. It is similar to the artist’s other fictions, very rarely spending time on concrete, specific accounts, instead allowing descriptions to linger on the uppermost surface of the events taking place. At the beginning the reader enjoys, obstacle-free, a story that goes nowhere— one that contains some tragedy but whose plotline remains flat. Huxiang, the filial son of a farmer, takes his paralyzed father back with him to his school dormitory and cares for him like a truly good man, maneuvering around other interpersonal situations in the dormitory and looking after his incontinent father without a single complaint. His father often “lies there in bed, a wry smile on his face, resigned to his helplessness.” This sort of cheap warmth goes entirely uncurbed here, running rampant as the easy tears that flood Zhiyin.

But that is where the everyday narrative ends and the illusory experiences begin. In Huxiang’s story, it starts with the appearance of the character of Auntie Zhang. Auntie Zhang has a total of three appearances, and each time she brings with her a specific and useful piece of popular science knowledge for Huxiang and his father. This character, however, is never truly established with her own place in the narrative. Rather, her importance as a person is dwarfed by the importance of the morsels of popular science she proffers. We can therefore see her role as one of a relatively faint tie between the reality of the story, and the world of the mind. Or to put it in more vivid terms, in this text we are able to definitively locate a path leading from reality to the world of the mind. Sometimes the link is reflected in a flickering flashback, and sometimes it appears in the dislocation of a line of thought. This gets into a question of narrative technique. The bridge between the two worlds not only exists in Faulkner or in the works of the nouveau roman authors, but also in Hemingway, the master of realism himself— particularly in The Snows of Kilimanjaro, where in a rare moment a flashback will fade us into the mind of the protagonist. The technique makes the connection between the two worlds of the author clearly visible, and from then on we are shuttled with ease between illusion and reality.

In her moves to prevent the erosion of the everyday narrative in her stories, Duan Jianyu reveals a fondness for frequently setting obstacles in the reader’s way. Most often she will introduce yet another “everyday” narrative into the mix, disturbing the rhythm and weakening or even preventing the deepening of the development of any one certain set of circumstances or events. With New York, Paris, Zhumadian, everything feels like a commercial broadcast, jumping into popular science tips, sharing ingenious tricks for how to make good use of used tea leaves, how to raise chickens, or even how to implant middle-school geography knowledge into works of fiction. The same method shows up conspicuously in other places as well, such as Plateau Life Guide—Now in Coming Art Project (2008), a popular science book that does in fact tell you how to go about survival in a plateau environment, but is in reality given to readers with the intention of bringing them through a weakened story: a painter very much like one in the Artists’ Association is sketching on the Tibetan Plateau, and she makes new friends, like the poet Chang Yao (a real person) as well as that “famous” Wang Kefu, portrayed as a sort of noble idiot. In the catalogue for her latest exhibition, 2012’s “Cousins,” Duan Jianyu published an essay by Sigrid Holmwood, in which the Swedish artist details her experience traveling all over China in search of and trying out different paper- making processes. Much of the text is taken up by introductions to different paper-making crafts designed for different types of materials. The account achieves the same result, though through different methods, as her earlier fictionalized account of American artist Julian Schnabel and his travels through Guangxi.

Duan Jianyu actively severs any possible form of narrative causality, turning realistic threads of narrative into pale undertones in the background. Huxiang’s story, for instance, does not ultimately develop into a model script for new age filial piety, and in the end Wang Kefu does not become a member of the Artists’ Association. This sort of ambiguity as we read leaves us feeling as if we are up against a surrealist, or absurdist, text. The reason for this is not only due to a juxtaposition of a large number of familiar images here made unfamiliar, but also due to the fact that, though the writing is loaded with details, reality still hovers at the surface, as depthless as a dancing shadow.

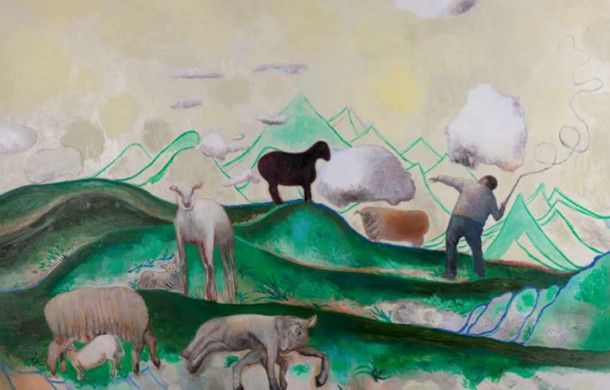

Nevertheless Duan Jianyu has also said that, in her textual works, the painting’s subject matter and style are determined mainly by the directionality of the text. When she paints out of a demand for a degree of consistency maintained between style and narrative, she makes every effort to select simple and unadorned techniques, utilizing rougher colors. To cater to the large proportion of works devoted to rural themes, she brings in coarse, big reds and greens and earthy yellows. This arises of course mostly out of her inherent aversion to and desire to rebel against what some might call the more “elegant” grays. She laughs at herself and the lack of refinement of her paintings— in the face of the pedantic traditionalism of those endless restrictions on the craft— unable to paint exquisite light dancing on the breasts of a female form. In the series “Wang Kefu: The Story of an Art Lover” (2007), in order to bring to life the story’s main character, an amateur fine arts enthusiast and who pines to enter the Artists’ Association, Duan set out specifically to painting factories to find paintings made by their workers. The colors are extremely choppy, the lines too rigid, and the artist will often only in the post-production stages add a few cursory effects, droppings drizzled on the top— in itself a plot line in the story.

Duan Jianyu’s paintings (as well as her installations) can to a certain extent be understood to be constantly wrestling with their relationship to narrative. Here it is not the painting that decides the narrative, but rather the narrative that decides the painting. We can certainly see that narrative intervention into painting is an important characteristic of Duan Jianyu’s creative process, as embodied in New York, Paris, Zhumadian, whose paintings on milk cartons and cardboard even came to serve as annotations to the overall novel. But this does not necessarily imply that her paintings can be classified as illustrations. We can also see, at the same time, that a novel with a single storyline is relatively isolated and separated out in the artist’s creations, while she works hard to transform her paintings into something of a paratext, transcending written language. Duan Jianyu has for many stories brought in the fictional constructions of an airline stewardess called “Sister” and a Santa Claus named “Red,” two figures that emerge from time to time in different series, even running into one another; for example in You Are Welcome, No.1 (2009) the picture shows “Red” to have seemingly had a sleigh accident, and not one but two kindhearted “Sisters” help him repair his reindeer ride, who seem to have fallen out of the sky—we never see their footprints in the snow.

This paratextual characteristic comes through as well in the artist’s fixation on “the journey.” From Schnabel’s Guangxi sketching to Plateau Life Guide: Now in Coming Art Project, and all the way to His Name is Red and Cousins, all tell stories that take place on the road. New York, Paris, Zhumadian is also all about the heroism two ordinary people in the world of the imagination need to complete their own world tour, while “Sister” the flight attendant is seen every time donning her blue uniform and carrying her suitcase through painting after painting, into the beginnings of all kinds of adventures. This stewardess, a character who speaks to the heart of Duan Jianyu’s creations, is a bit portly and could not be said to be beautiful, but is in fact very confident. In a massive oil painting titled Sister No. 15 (2008), the artist depicts the blue-suited stewardess and a traveling band of animals journeying together across a vast, golden desert. Present among the members of this team are tigers, zebras, orangutans, camels and elephants; if we follow along with the metonymy, it is much like Life of Pi, animals endowed with counterpoints to the cowardice, greed, and sometimes earnestness of humanity. This associative link can perhaps help us to enter into yet another dimension of Duan Jianyu’s storytelling.

It can be said that Duan Jianyu’s travels are fictional— that any destination, as long as it can be spotted on a map or in an imagination, is reachable. Tales of these frequently unending journeys, while often a source of convulsive laughter, also ultimately reflect a state of unsettledness in this world. The artist uses the word “wandering soul” to describe the sensation: “Going home, going home; the fragrance of wheat, a willow leaf in my mouth, a wide open heart, riding carefree on the tractor. Going home, it can’t be beat! A wandering soul, she belongs not to the city, nor to the country.” Duan Jianyu’s newest projects over the past two years, “Going home” (2010) and “The Muse Has Awoken” (2011), show the nude breasts of a goddess—an image defamiliarized by its juxtaposition with its surroundings: paddy fields, ravines, and rapeseed. The expression of this wandering-soul condition leaves a profound impact on the viewer. We will also recall the young girl in Beautiful Dream—Daughter of the Sea (2008), and her melancholy as she leaned against the coastal rocks. On her journey, Duan Jianyu has been inspired to call upon many images of women, sisters, country wives, and art goddesses. We would be mistaken to think that this is not at all a portrayal of the core of the artist’s own heart at work.

Duan Jianyu’s creations are windows again and again into the narrative adventures she embarks upon through her art. Sometimes, she projects her own narrative experiences onto the protagonists she dreams up; other times, she guides the audience into her narrative through their own perspectives. This time we will apprehend— as if we were there— the way in which an artist might become intoxicated by and immersed in narrative, losing herself in its maze. More and more in her recent paintings— such as Mother’s Sister’s Mother’s Cousin’s Husband Is A Chef (2012)— we see an artist who wants to return to the narrative power of painting itself, where the referentiality of narrative is much more blurred. But narrative has been, and will always be, the backdrop to creation. (Translation by Katy Pinke)