PERFORMANCE INTERVENTION

| July 15, 2013 | Post In LEAP 21

Sol LeWitt, Untitled (Wall Structure), Qiuzhuang

The openness of contemporary art with regard to medium and context allows for a wider range of formal possibilities, and its social orientation also serves to consistently expand the limits of these. The various approaches of different artists are continually extending the reaches of art’s net, and revising its relationship with society. In the contemporary condition, the dividing line between art and social life is increasingly blurry. For a while now, artists have thrown themselves into the mix, actively employing the body as their source material. The resultant networks of relation are far more diverse and complex than the traditional chain of person (producer) to object (a two or three-dimensional object provided for viewing) to person (audience). As a consequence, appraising the work of artists purely on the basis of the themes suggested by their actions and behaviors has proven to be fraught with problems. In Mainland China and the rest of the Chinese-speaking art world, artistic conceptions of personal subjectivity have expanded. The resulting artwork is no longer limited to unequivocal interpretations and expressions of political, systemic, and social reality. Rather, it delves more delicately into the multi-layered interactions between reality and the self, and, to a limited extent, dares even to reorganize these interactions.

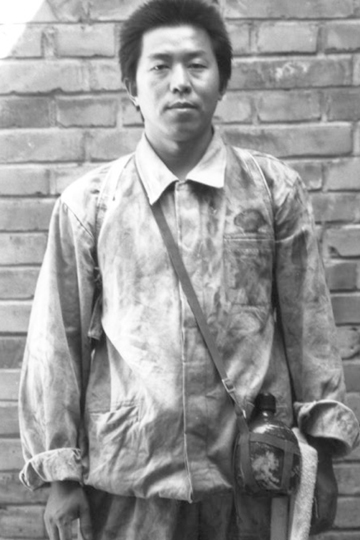

These challenges and reorganizations generally begin with a dedicated action or a series of related dedicated actions. These actions have long since melded performance and reality, but the subtle relationship between the two remains deserving of careful examination. More than 10 years ago, Yang Zhichao subverted his relationship to society by adopting other identities in two representative works: Within the Fourth Ring Road (1999) and Jiayu Pass (1999-2000), in which he played the roles of beggar and mental patient, respectively. By spending almost a week of living off of alms and a one-month stint in a psychiatric hospital, Yang produced performances that markedly diverged from the traditions of pure performance art within controlled settings. The artist leapt directly into a different reality by joining a set community of others. Like a Möbius strip, Yang’s chain of actions had no endpoint. He did not actually become the Other, but rather, returned to an ostensibly unchanged but actually reorganized so-called system of authenticity in which he continued to play the role of himself.

A similar work, Li Liao’s Consumption (2012), has recently spurred widespread discussion for its presentation of a clear role-play context. Li used ordinary and lawful channels to get a job as a worker at a Foxconn factory, and resigned after 45 days—exactly enough time to earn the money to purchase an iPad Mini. Li applied creative initiative and an explicit, goal-oriented approach to the objectified logic of the worker and the product. It was, indeed, a performance, particularly because of the differences that separated the artist from the workers: a chasm that could not be bridged by imitation. In Li’s own words, the workers, unlike the artist, “have no choice.” This work and other works of action art take creativity as their ultimate premise and goal. In contrast to Yang Zhichao’s performances, which were documented in periodicals and on online forums, Li’s actions were more quotidian, personal, and neutral. Both artists drew on artistic methods to open channels between parallel worlds and their own realities. These overtures, through the passage of time, became the works of art themselves.

When the young artist Tang Dixin jumped onto the tracks of the Shanghai subway in 2010, the performative nature of his actions clearly separated him from countless genuinely suicidal jumpers. Despite his sudden leap with the train only three meters away and the breathtaking scene of him lying on the tracks as the train screeched to a halt, the nature of the event was inescapable. Tang, who survived without injury, was detained for 10 days. The entire “work” was executed as a close interaction with the order of the real world, but it had no clear thematic direction. In completing the entire process by himself, the artist both constructed an abnormal means of intervening in society’s system and also of allowing the system to take the reins—up until the suspension of the cycle of events.

In contrast, when Song Ta sent the mayor of Guangzhou a video recording of the city’s subway system sustaining a simulated terrorist attack and being flooded by the Pearl River (The Mayor Watches a Horror Movie, 2011), the artist was drawing on his own nightmare scenario to fabricate a conceivable formal enactment. By indirectly delivering the action to the mayor, an audience of one, he located himself and the mayor at opposite ends of the linear action and made it so even the terrorist film itself—The Person Deep Down in the River—was entirely concealed. Song and Tang Dixin’s works provide examples of artists using different methods of personal action to intervene (or interfere) with social order. They differ from other, ostensibly more powerful works with more obvious political orientations, which always become their most eye-catching aspects. However, the aesthetic implications of Song and Tang’s methods—and the contradictory tension between those aesthetics and the apparent purposes of their actions—are not to be ignored.

Artistic action intrinsically includes the myriad possibilities of aesthetic propulsion, and these possibilities need not be separated from the content or themes that carry them. In other words, the specific contents and direction of actions are the external, visible elements of an artwork, but they do not possess any substantive relevance that can be separated from their internal aesthetic logic. This aesthetic logic primarily originates in the internal link between the artist’s subjectivity and his or her choice of medium. In a certain sense, it can be generally described as the artist’s inner desire, or even as the artist’s greatest motivation for becoming an artist (and not, say, a social worker or an academic). As the boundaries of performance endlessly expand, the distinction between performance and truth becomes ever more blurry and may yet vanish completely.

Li Mu and Gao Mingyan each had their own reasons to become jobseekers. Li Mu took advantage of an invitation to participate in an exhibition at the Netherlands’ Van Abbemuseum to work for a period as a salaried employee of the museum (New Job, 2010). The entire work process was itself the work of art, and it did indeed become part of the artist’s work experience. Gao Mingyan applied to positions in a variety of fields in his capacity as an artist and then drew on the process to create an interactive video installation, What Else Can I Do? (2012).

Projects like these, which were not intended to be performances, spring from various motivations and become diverse artworks. The aesthetic choices of the artist produce artworks of various forms; the dynamism of the body and its actions can even be seen as more central than the sociological implications of the artwork.

However, some artists have taken this issue a step further by penetrating more deeply into society, and producing a work of art has not always been the primary goal. Guo Haiping, like Yang Zhichao, brought himself into contact with the mentally ill. Rather than immerse himself in a psychiatric hospital as Yang did, Guo chose to promote and arrange artwork by mental patients, and even established China’s first art center for the mentally ill.

In a more blunt move, Hong Kong artist Chow Chun Fai ran for a seat on the island’s Legislative Council. In a cultural order in which mainstream politics has gradually come to dominate the arts, he assumed the most naive of approaches to participating in political society. For him, the only distinction between his self-subjectivity as an artist and his actions as a member of society was internal.

Hu Xiangqian’s Flying Blue Flag (2006) also merits mention here. Although he had not actually qualified for the ballot, Hu ran a full-blown campaign for office, deliberately muddying the waters (in contrast to Chow Chun Fai’s straightforward approach). However, his actions also served to preserve the demarcation between art and politics by creating a contrast. In this case, the artist used political reality as his medium while simultaneously maintaining a degree of autonomy.

There are also plenty of examples of artists using creative methods to formulate sharp critiques of societal events and systems. The Taiwanese artist Zoe Sun took aim at a corporate relations scandal at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum with two pieces, TFAM: Taipei Flat Arts Museum and Truly False Arts Museum— 正治. These representative works combined live physical actions with painting, installation, sound, video, and other mediums to provide a direct answer to the question of the necessity of art inventions: creative life can only occur within society.

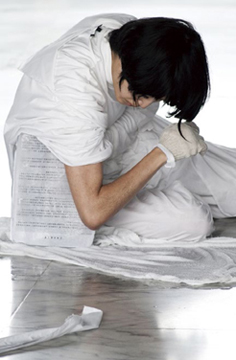

In a 36 x 25 x 17 cm cube of ice, Zoe Sun froze a three-page petition

letter written anonymously to the Taipei City Mayorby a group of Taipei

Fine Art Museum employees. She then used various parts of her body to

melt the ice, laid the three wet pages of petition on the lobby floor, and

left the museum.

Looking at these examples, it would be easy to come to the conclusion that performance art (or the use of the artist’s own body within his or her creative practice)—and perhaps even the entire extent of figurative or direct interventions and references to society in contemporary art—is a refuge from an oppressive system. Of course, producing such art quite possibly means returning to the system as a commodity. This sort of hasty verdict to a certain degree reflects the fatigued state of art with relation to reality, but it perilously overlooks art’s autonomy, which should stand for our aesthetic character.

The two instances of the “Everybody’s East Lake” project in Wuhan in 2010 and 2012 attempted to use wide-ranging art activities to create a public discourse about the plans to fill in the lake and build an amusement park. Artists and ordinary citizens participated in a variety of creative work (mostly performance art), and taken as a whole, the project was a social program. Due to the collective and social nature of “Everybody’s East Lake,” the project possessed a diverse structure, and it could almost be seen as a realization of the “autonomous art” concept postulated by Adorno. This autonomy becomes a way for art to use its own aesthetic nature to avoid being commandeered by politics or reality. It is also evident in the way in which art influences society primarily through subtle, indirect effects on the popular consciousness. Thus, the artistic actions taken by the non-artists who participated in “Everybody’s East Lake” possess a special profundity.

Of course, we must also remember one other kind of creative action that intervenes in society: the kind that promotes interpersonal exchange through contrived circumstances. For example, in his Going Home Projects, Pak Sheung Chuen sought out volunteers within an audience to take him home, effecting a degree of interactivity to reverse the roles of artist and audience.

Li Mu’s The Blued Books (2008-2009) also employed a special setting: a juvenile correctional institution. In highly controlled circumstances, the artist communicated with the young detainees through conversation, books, and painting. This form of art has much in common with the work of public welfare organizations, but its aesthetic aspect lends it a form of abstract autonomy. Indeed, aesthetics release art from its powerlessness in the face of reality and constantly produce introspective tension.

Xu Tan’s Keywords School, a more multifaceted project, employed the abstract realm of speech and language to map out the intersections of social thinking over the course of several years. This project rose to the level of artistic research into societal ideology, showing that art has transcended the simple modes of sensory experience and conceptual logic, and highlighting the possibilities of art within constructions of knowledge.

In Li Mu’s ongoing Qiuzhuang Project, a series of reproductions from the collection of the Van Abbemuseum in the Netherlands have been transported to the artist’s hometown. The project uses art, knowledge, and experience to create new relationships with the familiar village, and it explores the possibilities for mutual cooperation and influence. Through this process, the artist found that rather than art influencing the outside world, it was he himself who was influenced, compelled to reexamine his relationship with art. Performance artists are always interacting with people, objects, and networks, and in this way they accumulate an understanding of complex relationships and gain the power to transform art from within. This autodidacticism is a crucial aspect of artistic interventions, which go beyond the traditional efforts of art to fend off the erosive force of the social system. They offer artists a means of fashioning their own aesthetics through the process of interacting with society.