THE EVERYDAY AND THE CORE—LlN XUE’S UNTITLED DRAWINGS

| September 2, 2013 | Post In LEAP 22

Courtesy of Gallery EXIT and the artist

THE EVERYDAY AND THE CORE—LlN XUE’S UNTITLED DRAWINGS

Lin Xue (b. 1968) achieved instant fame when his work was shown at the 55th Venice Biennale this year. Curator Massimiliano Gioni had invited Lin to participate in “Il Palazzo Enciclopedico.” Prior to the show, no more than a thousand people had seen Lin’s work or had heard his name. His small group of followers largely consisted of collectors, art lovers, and Internet surfers who stumbled upon his name and JPEGs of his work. When Gallery Exit organized Lin’s first solo exhibition in 2008, Lin provided no artist statement and was absent for the opening. To date, the life of Lin Xue remains shrouded in mystery. With little background information to go on, one relies on his artworks, a few media reports, and catalog texts to understand the artist and his practice.

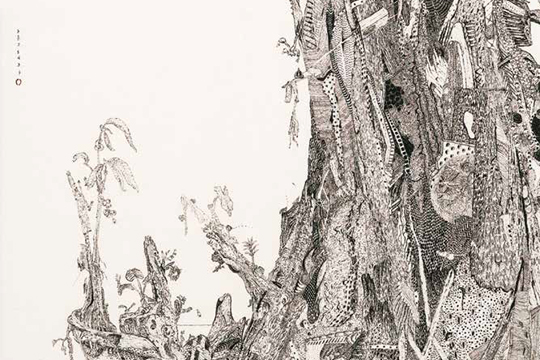

SUCH AN ENIGMATIC man as Lin Xue creates equally compelling work. His drawings appear to depict a kind of landscape composed of rocks, floating kingdoms, birds, and flowers. These pictorial elements codify a hidden map of other, self-sufficient space. Presently, Lin has created no more than 100 drawings, all of which are untitled. His drawings, made with ink on paper, are typically horizontally or vertically composed, and overlaid with seals and calligraphy on the side. While these drawings convey a likeness to Chinese ink paintings, upon closer inspection, they are distinctively different from the traditional discipline.

Lin Xue began to draw as early as the 1990s. In 1995, he participated in the group show “Manulife Young Artists Series.” In those days, The Hong Kong art scene thrived with art organizations and associations. The Chinese university and Hong Kong university both operated art departments, and professional schools offered regular art classes. Lin did not seek formal art education, nor did he join any collective. After participating in the 1998 Hong Kong Art Biennial Exhibition, Lin disappeared for the next 10 years with no public release of new work.

Lin Xue resurfaced in the twenty-first century with four consecutive years of solo exhibitions. By then, most of his contemporaries had received professional training, come to emphasize technicality and theory in their work, maintained studio practices, and regularly attended opening parties. Lin, on the other hand, maintained his independent practice of recording all that he saw, heard, thought, and felt onto ink on paper. How has the silence of solitary life impacted his work? In the years during which he abandoned painting, how did his experiences and thoughts impact his later aesthetic style? I am unable to answer here, but I can provide some clues.

TRACING THE EVERYDAY

IT IS In our nature to love nature. Like a virtuous ancient Chinese man, Lin Xue is disinterested in fortune and fame. He lives a quiet life in New Territories, Hong Kong. Originally from Fujian, Lin migrated to Hong Kong at age five. As a child, he frequented Shing Mun Country Park and loved long walks and hikes. In his twenties, Lin gave up his job to live in a remote mountain range on the Mainland. There, he felt like he was at the center of the world. One summer, when the sun was setting, he walked through the wild fields and watched smoke rise from the foot of the mountain. He wept as he realized that the world too, is one wisp of smoke, as the saying goes, one in All and All in one.

When Lin first returned to Hong Kong, his work was selected for Hong Kong Contemporary Art Biennial. Then for next 10 years, financial concerns led him to abandon his art practice. After a decade of inactivity, he eventually picked up his bamboo stick, dipped it in ink, and began to paint again. Lin explains that the bamboo sticks are not artificial tools. He typically exhausts one stick per drawing, and replenishes his supply by collecting sticks in the woods. The act of drawing, for Lin, is a direct record of what he sees in the mountains.

Lin considers himself an imitator of nature; he aims to “to see without interpreting.” He seeks to draw from direct observations, and avoids infusing his drawings with any further meaning. He tries to think as little as possible during the process. Seeking to imitate nature, he conveys an immediate imprint of his daily sensibilities. Western landscape values realism, while Chinese landscape focuses on the play of ink and brush and the expression of emotions. Lin’s drawings do not objectively replicate our present world; like the literati, Lin imbues his landscapes with a personal vision. Through daily observation of nature, he experiences the world. He sees forms of nature, internalizes them and reflects upon them. With these forms of nature, Lin communicates his subjective view of the world.

According to the artist, “The paper is a pond by which I quietly sit. I am waiting for fish to jump, I am waiting to capture the glow of its scales. This glow is not my imagination, but a reappearance of what I have seen in the mountains.” In that spark of inspiration, he sets down on paper a depiction of flowing thoughts and wild imaginations infused with his experience of reality. Lin’s vision is filtered through his obsession of nature; he sees the texture of stones in a messy pile of books. A drawing is not only a record; it is also an attitude. Since 2008, Lin has been maintaining a natural practice of recording daily sightings in the mountains.

TO DEPICT THE CORE

LIN XUE’S DRAWINGS contain multiple layers of readability. Beyond coherent pictorial forms, the viewer must also delve deeper into the image, to inspect the minute details, in order to detect unlimited natural ecology as seen through the eyes of the artist.

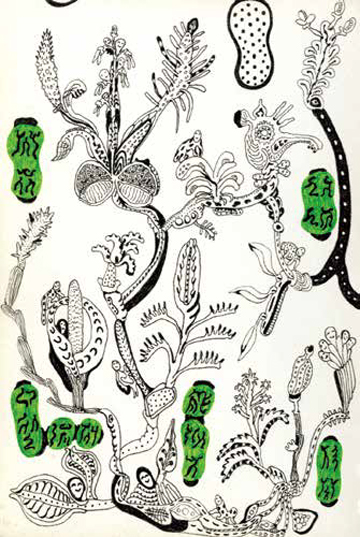

The drawings are like the artist’s monologue, the accompanying calligraphy a secondary narrative. The latter echoes the Chinese tradition of dedicating poetry to paintings; these dedications also look like the artist’s own comments on his drawing exercises. The calligraphy appears to supplement the drawing, but their literary meaning is too difficult to understand.

Lin’s desire to paint was first inspired by his visit of Taiwanese amateur artist Hong Tung’s 1990 retrospective at the Hong Kong Art Center. Lin’s reliance on intuition, his style of drawing, calligraphy, and seal all reflect strong influences from Hong Tung. As a child, Lin was fascinated by words that he could not understand. Similarly, Lin’s drawings are like visual codes of a private language through which the artist channels the objects in front of him. Lin’s drawings reveal a unique relationship between surreal landscape and language. The viewer lingers between understanding and incomprehension. The calligraphy on the side of the drawings does not distract the viewer from appreciating the simple emotions of the drawing. Like the Tang poet Li Shiyin’s Untitled, Lin’s nameless drawings are like esoteric love poems, conveying deep and unspeakable feelings that maintain a difficult relationship with words. In the 1990s, Lin Xue began to use bamboo sticks as a drawing tool, which critically contributed to the formation of his distinct drawing style. Every creation is like a flower that sprouts from casually spread seeds. It takes years to nurture these seeds and only few of them reach eventual flowering. The flowers resemble one another, and the viewer contemplates them, pondering the cosmology of the universe. The artist records his unmediated emotions onto paper, in delicately drawn landscape. With points and lines, thick, thin, dark, and light marks, Lin creates a compressed pictorial space that embodies layers of rhythm, secret orders. Upon close inspection, one may witness various details and material expressions. When Lin first started to draw, he wanted to create a never-ending landscape. Over the years, his continuous striving towards this goal, revealing his deep connection with nature. In the past 10 years, Lin has become increasingly calm and objective in his practice. The triptych Untitled (2000) depicts a uniform composition organized by clear spatial divisions. From the bottom of the picture plane, each drawing begins with a layer of sea, from which vertical islands then rise towards the clouds. All of earth’s life forms are condensed into one image, while a white circle filled with microcosmic creatures floats in between the waters. These creatures echo various shapes found in Lin’s daily records of mountain sightings. Observations from his daily exercises culminate into larger drawings.

Lin Xue’s recent series of 12 drawings shows the artist’s growing confidence in creating large-scale works. Ever since he was a child, Lin has been fascinated with the peach pits he finds in the woods. Every time he comes across one, he carefully picks it up for inspection. On one rainy day, he went up to the mountains. Suddenly, the rain grew too strong to bear, and he found refuge in a pavilion. Once it had calmed, he set out again—but the weather worsened, this time with harsh wind and thunder. Under a tree, he noticed a peach pit, and he felt impassioned with nature. He became so ecstatic his mind went blank. Inspired by this experience, the series of 12 drawings adopts the shape of the fruit. Every drawing depicts a different angle; one fruit stands at the center of one painting, floating between sky and earth. The fruit embodies layers of mountains and peaks, in between which life is formed. Light ink and small points symbolize the rain and clouds that fall from the sky to ripple across the sea. The drawings depict an intimate, poetic, and imaginative space that still requires the viewer to observe with a keen interest in order to sense the infinite subtleties within.

“There are no beasts that do not bloom, there are no birds that do not bloom.” This poem, imbued with philosophical connotations, beautifully resonates with Lin Xue’s work. The line is quoted from the Yi people’s epic poem Meige, which speaks of reproduction and praises the spring wind and blooming life. Lin loves origin myths as told through epic poems. His recent exhibition “The Sixth Day” refers to the Christian story of Creation. “Without knowing how to sink, one can never know the joy of rising,” says Lin. Perhaps through his various life experiences and his love for nature, Lin has fostered a desire for what is beautiful from the perspective of man. As with love, and as with William Blake’s words “a heaven in a wild flower,” Lin Xue’s untitled paintings are small but great, ephemeral but eternal, ever evolving but always the same.