LET PANDA FLY

| October 11, 2013 | Post In LEAP 23

Let Panda Fly opens with an aerial shot—accompanied by emotional music—of four children on a mountain road, setting out into the morning sun. The powerful scene seems almost purposely to leave the audience in suspense. It is the beginning of the film, but the end of the story. All of the “pandas” have long since disappeared.

Let Panda Fly received a meager 2.6 score on Douban, with commentary limited mostly to mockery. Many condemned the film before it had even been released, some audience members were in fumes over the boring plot-line, and a large number of people discussed it in relation to the blockbuster Kung Fu Panda, seeing it as a lousy domestic attempt to boycott the Hollywood film. These responses were within artist Zhao Bandi’s expectations for the film. Over the past ten-plus years, Zhao has been consistently in the public eye, stirring up conversation over his appropriations of the panda symbol. A panda fashion show, the Panda Olympics, his stand in 2008 against Hollywood’s Kung Fu Panda—the list goes on and on. Early on he abandoned the easel-and-paint approach to artistic practice, opting instead for manner of strange panda-based social intervention. If it weren’t for frequent news of the astronomical prices for which his early paintings sell at auction, Zhao’s former artistic identity would already have faded far from memory. His directorial debut Let Panda Fly hit theaters everywhere on June 1, National Children’s Day. With this, not only did he successfully push his own video work in front of a national audience, realizing an artist’s ultimate movie dream, but he also yet again presented a Zhao-style challenge to the public through artistic action— this time provoking currently prevailing filmic aesthetics.

Let Panda Fly attempts to tell the poignant story of over 20,000 young people across China—from Hebei to Sichuan to Beijing to Gansu—who create paintings, sculptures, dances and installations based on the topic of the panda. The works are shown at SH Contemporary, exhibited at the Henan Art Museum, and even end up in the hands of collectors. The proceeds, amounting to over RMB 1 million, are then donated towards the construction of a center for the elderly on the Yellow River, in the end providing a home for over 60 senior citizens. This is a real story, with a real happy ending. Three years ago, Zhao Bandi went with a team to survey the Yellow River in Henan with a plan for his new film project in tow. He met with local schoolteachers to discuss an initiative whereby students would use every inch of their imaginations ultimately in exchange for a home for the elderly. Zhao’s team would film the process. In the end the charity project succeeded, from start to finish.

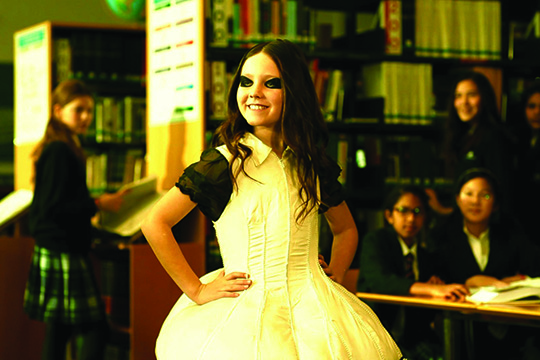

Though the film would seem to fit into the documentary category, and though every character is a product of reality, played by the original person him or herself, the overall presentation is kept, through exaggeration and a degree of ambiguity, somewhere between the real and surreal. The prologue opens with mysterious “Panda People:” one a man (perhaps Zhao Bandi himself) wearing a suit and donning a panda headdress, and the other a dancing Panda Girl. They walk through the streets attracting the attention of passersby, when one little boy named Ai Zele—driven by his curiosity and fancying himself a detective—begins to follow them, embarking on a tireless pursuit in search of the truth of the Panda People. Through the boy’s eyes we learn about the charity campaign: a project of panda-inspired creativity in exchange for a new home for the elderly. Ai Zele’s investigation into panda creativity becomes the central thread to the story, and as he comes to understand the idea behind the campaign, he ends up playing the role of the moderator, interviewing several participating students and giving us windows into their stories. Zheng Yuebo and his brothers, hoping to donate their family’s only car in order to raise funds, hold a democratic discussion with their parents on the matter. When Zheng Yuebo’s father asks him “Where did you get the idea to give away our family car?” Zheng responds, smiling shyly, “It’s you who has always taught me to care for the elderly.” Hearing a truth he can’t deny, his father cracks an awkward smile. In China, for a well-off family to donate their only car to charity is essentially unimaginable; Zheng Yuebo’s request is forthright and incredibly courageous. The intensity of the family meeting gives way to an unresolved awkwardness.

On the one hand, the surrealist texture of the film derives directly from the degree of imagination inherent in the “creativity in exchange for a home for the elderly” initiative itself. On the other hand, it arises from the affected way in which the director has the actors re-interpret original details from their own true-life experiences. Students from Chengdu use panda droppings to erect a tribute to Venus, calling their work “choumei:” a pun on the very materials used, as the word means “shamelessly smug,” but can also literally translate to “stinking beautiful.” Meanwhile, a student named Guo Jie, who does not say a word as his teacher and fellow students discuss the panda creativity project in class one day, comes forward after class to speak with the teacher in private. Guo Jie, whose parents work in trash collection, confesses that he wishes to collect scraps and create his own robot panda with them. Persevering through doubt and tribulation, Guo Jie ultimately does create a robot panda, and even successfully exhibits it in a museum. The robot’s head is an old computer, and from its monitor Guo Jie broadcasts himself saying “Although some may look down on my father’s profession, I am not ashamed.”

In the second half of the film, collectors Uli Sigg, Budi Tek, and Tek’s wife arrive at the “creativity in exchange for a home for the elderly” exhibition. Facing the camera, they each discuss their understanding of and relationship to art and creativity. “My Dad is a Panda,” an essay by a 12- year old girl from Zhengzhou named Zhang Lintong, is bought by Sigg for RMB 100,000. Let Panda Fly—in using art for charity, challenging mainstream aesthetic values, and re-envisioning the panda symbol at the same time— carries with it too many of Zhao Bandi’s expectations of and hopes for art. The film in its entirety presents to the audience Zhao’s own exquisite utopia: in response to the practical demands of reality, the artist uses his creativity to produce works, and then uses art fairs, exhibitions, media outlets and so on to disseminate these works and sell them; in the end, he gives back to society.

The plot line of the film does not follow an arc, nor does it have any real ups and downs. There are no knockout camera angles or grand feats of production; everything comports with mainstream aesthetics, as in whatever one could find in any other movie out right now. Those familiar with Zhao Bandi’s personality will come across an abundance of little details over the course of the film that will make them smile to themselves or bring a hint of tears to their eyes. The problem is that the director is trying to say too much at once; his critique of reality does not achieve the strength of other contemporary video works, nor the depth of topic of a typical documentary film. The relationship to reality is ambiguous, and its humor too dark to comprehend; these make the work both difficult to evaluate and easily subject to castigation. The film’s final scene is two astronauts dressed in panda suits landing on Mars. Letting pandas fly to the point that they rocket out of the earth: enough to prove that the director’s ambitions do not end here. (Translated by Katy Pinke)