An Exhibition About Exhibitions: Mountains and Ethnographies

| December 17, 2025

Yi-Fu Tuan’s Romantic Geography: In Search of the Sublime Landscape (2013) features a brief section on “Mountains,” in which he traces the evolution of European imaginations and perceptions of mountains along two trajectories. The first casts the mountain as part of a Christian symbolic system that “confused the mind” until its secularization and disenchantment after the 18th century. The second trajectory regards the mountain as an emblem of fear prior to the 18th century, but in the 18th and 19th centuries, it was reimagined as a fashionable site for the pursuit of sublimity and health, and later became a political metaphor for fascism. While Tuan provides a fascinating and clear historical account, he also suggests that a kind of universality lies in the symbolic meanings associated with the vertical elevation of mountains across cultures. He cites examples such as Mount Meru from Indian mythology, China’s Five Sacred Peaks, and Japan’s Mount Fuji. Nonetheless, his discussion of mountains and the sublime remains firmly rooted in Western histories and conceptual frameworks.

“An Exhibition About Exhibitions: Mountains and Ethnographies” discusses mountain-related exhibitions that have emerged within the Chinese contemporary art scene over the last five years. The use of the term ethnography does not necessarily imply a direct affiliation with anthropology. Instead, it draws on cultural specificities and the authorial presence embedded in ethnographic inquiry. To some extent, it unsettles the Western notion of the sublime in mountains as discussed by Yi-Fu Tuan. On the other hand, it also revisits Tim Ingold’s reconsideration of the relationship between anthropology and ethnography. In his 2014 article “That’s enough about ethnography!,” Ingold argued that anthropology and ethnography are fundamentally distinct. Anthropology, he writes, is a discipline of “doing,” probing into ways of living with others. Ethnography, by contrast, is about “writing,” and is constituted by documentary and descriptive methods of representation. Ingold is correct in insisting that the two should not be conflated. However, he does not delve into the question of whether ethnography is necessarily confined to documentation and description—or to what extent documentary and descriptive media might also be creative. In his 2016 short essay “Ethnography: Provocation,” cultural anthropologist Andrew Shryock fiercely criticized Ingold’s approach, arguing that “his bad ethnography is not the kind most of us did, or will do, and his good anthropology is not one he’s prepared to show us how to do. Methods are of minimal interest to Ingold, even as craft. Instead, he offers us a glistening array of attitudes, doctrinal stances, and metaphoric imagery.”

Attitudes, stances, and metaphors are undoubtedly essential to both anthropology and art—but equally vital is the question of method. As we advocate for a promising future of co-creation between art and anthropology, we must move beyond abstract discussions of concepts and care. How, then, should we move forward from living with and learning from others? This is precisely the question that ethnographers continually grapple with: the uneven textures of the real world demand direct engagement from the fieldworker. The process of ethnography, in fact, both precedes and far exceeds its eventual “writing.” Ethnography, then, is also a form of making—one that generates heterogeneity within the field itself. It dialogues with art at the level of practice—how reality is perceived, understood, and transformed. Indeed, it is such moments of entanglement, confusion, struggle, and vulnerability within concrete practices and research that often mark a shared point of departure for both artistic and ethnographic creation.

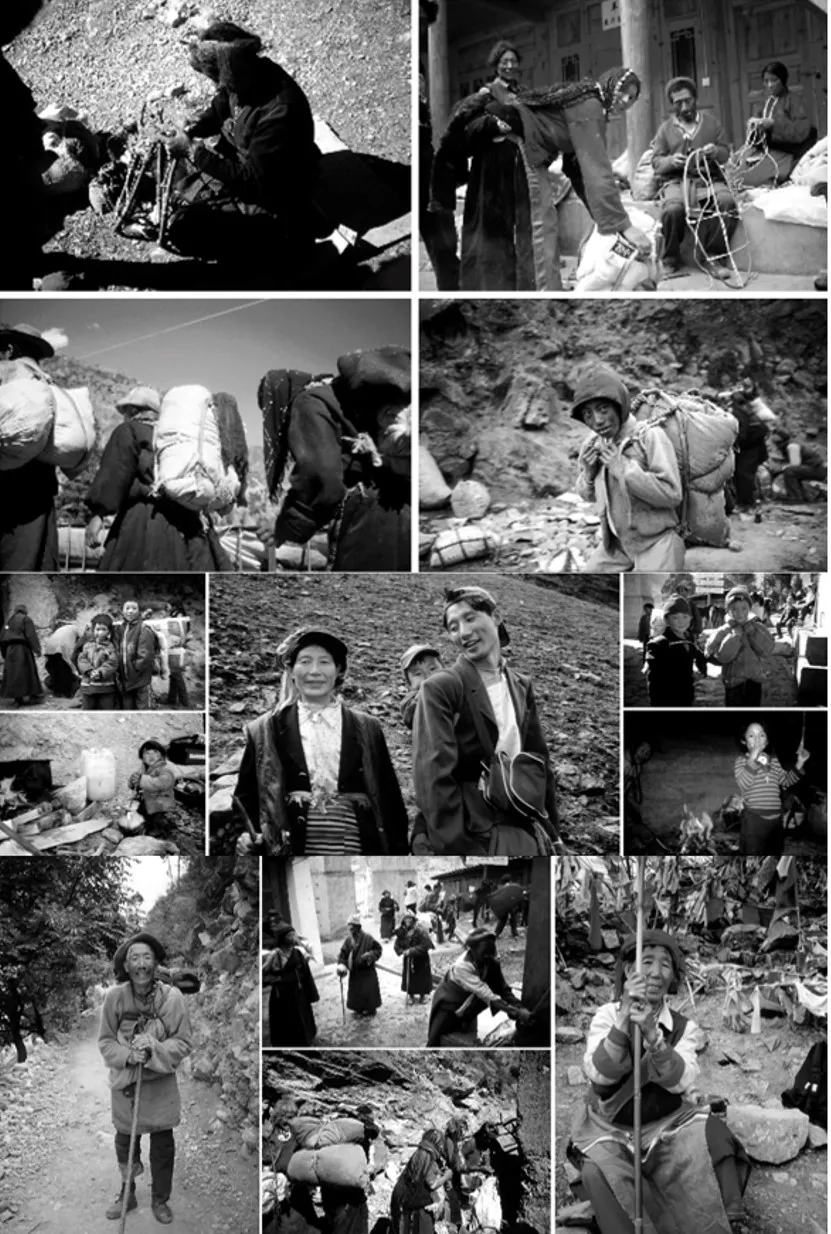

In “An Exhibition About Exhibitions,” mountains are not merely objects for aesthetic contemplation. Instead, they are agents with geographical and historical depth, intertwined with the emotions, memories, projections, and labor of those who create with them. This “exhibition” starts with a screening by ethno-filmmaker Guo Jing at the Guangdong Times Museum in early 2022. During the event, the museum presented a chapter titled “Tales of Mountaineering” (2019) from the documentary series Legend of Kha-ba-dkar-po, which Guo co-filmed with Tsering Drolma, a local villager from Yunnan. Strictly speaking, the Legend of Kha-ba-dkar-po is not merely a set of documentaries about the Deqin Tibetans and their belief system surrounding sacred mountains. Rather, it is an experimental work shaped by the ongoing re-editing of a body of video footage. Guo has been collecting footage since his first fieldwork trip to the sacred mountain Kha-ba-dkar-po in 1997, ultimately amassing 110 DV tapes. He personally edited and reassembled over 50 of these tapes, producing multiple versions and iterations of the film.[1] This working method not only enacts the documentary function of visual ethnography, but also embodies a kind of curatorial thinking—one that gestures toward an open-ended, deliberately unfinished state, or rather, a condition of incompleteness intentionally embraced by the creator. Many clips capture the everyday lives of Tibetans: their labor, their laughter, their discussions of mountain accidents and legends, and their acts of circumambulation, among other things. Perhaps more importantly, the filmmaker never conceals his presence in these seemingly mundane clips. The interactions between Guo and the locals—mediated through the camera—are not only documented but also foregrounded. What the viewer sees is not just local life, but how locality is performed and made visible within a vivid, reciprocal context.

In June 1998, Guo Jing photographed villagers harvesting wheat at the foot of Kha-ba-dkar-po.

Courtesy the artist

The Legend of Kha-ba-dkar-po documentary series is essentially a visual counterpart to Guo’s 2012 written ethnography Tales of Kha-ba-dkar-po. This is not to suggest that the former serves merely as a visual supplement or translation of the latter. Rather, they can be seen as independent yet deeply interrelated works. Guo Jing opens Tales of Kha-ba-dkar-po with passages that deeply resonated with me. Chief among them is his reflection on Kha-ba-dkar-po’s localized sublime or grandeur: “At the time, to me, the snow mountain appeared solely as a field of white. I had not yet witnessed its shifting colors, nor noticed the traces left by changing seasons and human activity. It was a ‘natural’ mountain—composed of rock, ice and snow, scree slopes, high-altitude coniferous forests, and V-shaped valleys—rendered as clearly and plainly as in an oil painting or photograph. Its grandeur moved me, but I had no means of responding. I did not know how to burn incense, nor could I chant sutras in Tibetan—let alone enter its spiritual world or commune with it in any intimate way. With its sharply drawn boundaries, it kept all outsiders at a distance. Even with our most refined technological tools, we were unable to penetrate the mountain’s surface landscape.” Another brief but evocative sentence struck me, vividly conveying how the mountain summons the creator’s presence: “The mountain doesn’t move, yet people flock to it.” He originally used this sentence to describe the cacophony of voices surrounding the 1991 mountaineering accident on Kha-ba-dkar-po, the local belief system, and the expansion of tourism. Yet it also aptly reflects the diverse approaches to mountains found in the various exhibitions and among the artists involved in this “Exhibition About Exhibitions.”

Pilgrims circumambulating Kha-ba-dkar-po in 2003.

Courtesy the artist

Zhuang Hui’s solo exhibition, “Qilian Range, Redux,” curated by Karen Smith, opened on April 24, 2021 at Galleria Continua, Beijing. The exhibition was both a continuation of the eponymous show curated by Colin Siyuan Chinnery at the same venue four years prior, and a showcase of Zhuang’s recent work. Zhuang traveled alone—by car and on foot—through the Hexi Corridor, where he was born and raised. A video installed inside a yurt in the exhibition hall shows him attempting to lever a massive rock with a wooden stick (Qilian Range-22, 2019). He wandered naked through the Hexi Corridor and the Qilian Mountains, striking a gong (Qilian Range-26, 2019). He also engraved QR codes into rocks at five separate sites—human traces that would guide those who “discovered” them in the vast wilderness toward local knowledge and histories tied to the Qilian Mountains. In the exhibition, the artist surrendered both his body and mind to the mountains. These actions, though seemingly futile, were gestures toward freedom: the artist would not forgo action simply because he understood the rock would remain unmoved. Instead, he found release in the wilderness and among the mountains. Writing in ArtChina about Zhuang’s 2017 solo exhibition, art critic Li Fan observed: “The distance between man and mountain is relatively vague and ambiguous. It’s hard to say whether it is man who roams the mountains, or whether the mountains are human by nature—who serves as whose backdrop, and who becomes whose annotation… The posture here is open, allowing any childlike spirit to run wild.”

Zhuang Hui, Qilian Range-26, 2019

10 videos, color, sound, 2′01″, 3′00″, 2′01″, 2′55″, 1′26″, 5′38″, 52′00″, 42′00″, 3′45″, 2′11″

Courtesy Galleria Continua and the artist

Installation view of the exhibition “Zhuang Hui: Qilian Range, Redux”, 2021, Galleria Continua, Beijing

Photo: Dong Lin

Courtesy Galleria Continua and the artist

The artist Cheng Xinhao also harbors a deep affection for the mountains of his hometown. Six months after Zhuang Hui’s exhibition, Cheng’s solo show “Floating Wood, Drowning Stone,” curated by Wang Paopao, debuted at Tabula Rasa Gallery in Beijing. The exhibition poster shows the artist standing in the Alps, taken from a still from his 2021 video work Der Rhein, produced during a residency in Switzerland. This piece exemplifies a recurring theme in Cheng’s recent video works: the artist’s body is cast into expansive landscapes through prolonged, meditative treks. Interestingly, though the setting is the Alps, the artist’s central concerns remain rooted in his hometown of Yunnan. In his artist’s statement for the work, Cheng recounts and poses questions as follows: “On May 13, 2021, I started walking from Oberalppass, the source of the Rhine River, bringing with me experiences from the mountainous regions of my hometown, Yunnan…I came from Yunnan…it is a place like Switzerland, with many mountains, as well as water systems divided by north-south mountain ranges… Can a body carrying the experience of Yunnan enter another river that traverses European countries? What kind of dialogue might such an encounter produce?”

Cheng Xinhao, Der Rhein (still), 2021

Single-Channel 4K video, color, sound, 35′31″

Courtesy Tabula Rasa Gallery and the artist

This fascinating approach—using foreign landscapes as reference points for his hometown—had already appeared in Cheng’s 2019 work, To the Ocean. This nearly 50-minute film documents the artist’s 19-day walk from Kunming to the China-Vietnam border along the Yunnan–Vietnam railway, covering a distance of 446 kilometers. With a hiking backpack, he picked up a piece of ballast for every kilometer and placed it in his bag. Each day, he would also write letters to an imaginary friend named X, sharing his encounters, joys, physical pains, and memories from his journey. These letters were later compiled in his 2023 book, 24 Mails from the Railway. In the letter from day fifteen, he recounts how Georges-Auguste Marbotte, an accountant for the French engineering team that constructed the railway, once compared Yunnan’s mountains to the Alps of his own homeland. In this way, To the Ocean and Der Rhein enter into an intertextual dialogue. As Cheng wrote in one of these letters:“Maybe we are all using our hometowns to evaluate strange terrains. Or, conversely, we go to unfamiliar places, only to relocate our hometowns.”

Installation view of the exhibition “Cheng Xinhao: Floating Wood, Drowning Stone”, 2021, Tabula Rasa Gallery, Beijing

Courtesy Tabula Rasa Gallery and the artist

In the summer of 2023, CLC Gallery in Beijing presented Yu Guo’s solo exhibition, “From Ridge to Ridge.” For Yu, venturing into the mountains is not only a way to position oneself, but also a form of physical training in how one senses space and scale. The 55-minute video work Mountain Range (2023), featured in the exhibition, seems to carry the tone of an academic ethnographic film. The work centers on the Altai, Tianshan, and Kunlun mountain ranges, all situated in Xinjiang—a region long examined by anthropologists and ethnographers. Yu deliberately structured the film using chapter divisions modeled after the table of contents of an academic thesis. In sections addressing “local knowledge,” he even includes actual scholarly citations. Yet this seemingly formal and canonical editing is continually disrupted by segments resembling travelogues. In one instance, the artist is seen interacting with local children who spontaneously burst into a viral social media song: “I am from Yunnan—from Nujiang, Yunnan.” Yu moves through the mountains, using his camera and body to engage with the varied geographies, events, histories, and people of each locale. These serendipitous encounters inject into his video practice a kind of vibrant openness that resists institutionalization, creating fissures within the otherwise “rigid” structure—prompting viewers to question standardized, singular narratives of place.

Yu Guo, The Mountains, 2023

Single-channel digital 4K video, color, sound, 55′00″

Courtesy the artist

Installation view of the exhibition “Yu Guo: From Ridge to Ridge”, 2023, CLC Gallery Venture, Beijing

Courtesy CLC Gallery Venture and the artist

In the same year, Liu Yujia’s “A Darkness Shimmering in The Light” curated by Mia Yu at Tang Contemporary Art featured the eponymous video work projected on a large screen in the main gallery. Although the artist listed several anthropological and ethnographic works in the credits as influences, including Soul Hunters (2007), The Mushroom at the End of the World (2015), and Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man (1991), and the film also demonstrated her interest in the livelihoods and ritualistic beliefs of local people in the region of Changbai Mountains, the artist preferred to call her creative approach the “travel videography.” In her working method, “travel” distances itself from the currently popular model of “research-based art.” It is more akin to “entering a regional area empty-handed,” retaining the author-centric tradition of the travelogue: Daoist priests practicing martial arts, deer roaming the forest, shamans communing with spirits—all recorded by the artist’s camera, yet “transformed” into “stories” through the artist’s imagination. She once stated, “Many stories in the exhibition might simply appear as documentary snippets in terms of visual images, but their function is absolutely not to provide documentation. It is rather a kind of creation. This is not about how to translate reality, but about how you perceive and imagine reality.”[2]

Liu Yujia, A Darkness Shimmering in the Light (still), 2023

Single channel 4K film, 16mm film transferred to 2K digital video, color, 5.1 surround sound, 64′17″

Courtesy the artist

I screened this film for students in my Anthropology of Art course at Peking University, encouraging them to reflect on how Liu Yujia “de-disciplined” ethnographically significant material while simultaneously addressing current concerns in the discipline of anthropology, including the deconstruction of the nature-culture dichotomy and the co-existence of multiple species. Among those students’ responses, one comment deeply resonated with me, “If we don’t understand why mountain cliffs groan, it becomes impossible to recognize those people who live among the ranges of mountains and forests.”[3] A Darkness Shimmering in The Light (2023) might not be endowed with any ethnographic “substance” in an anthropological sense, but the tension between real-life sourcing and fictional narratives distinctly creates an ethnographic “texture,” inviting us to reconsider the relationship between ethnography and reality.

Installation view of the exhibition “Liu Yujia: A Darkness Shimmering in the Light”, 2023, Tang Contemporary Art, Beijing

Courtesy Tang Contemporary Art and the artist

On July 13, 2024, the Guangdong Times Museum unveiled “Photographic Geomancy: Images, Fieldwork, and the Poetics of Geography,” a group exhibition curated by He Yining. Many of the participating artists explore mountain-related themes in their works, including Cheng Xinhao and Liu Yujia, whose works were previously discussed. The exhibition’s first chapter, “Retracing Ancient Terrain,” begins with Taca Sui’s video piece, Jiulong Mountain (2017—). Viewers journey through the caves of Jiulong Mountain via photographs, leading to Guo Jiaxi’s photography book, Ling Mountain Records (2021). After navigating a corridor formed by Lin Shu’s “Pagoda” series (2023), Zeng Han’s monumental landscape photograph, Echo of Shanshui 23, from the series “Meta Shanshui 09” (2021), descends from the ceiling. This striking image depicts water cascading down towering peaks, drawing the eye to the mountainside forests and scattered rocks below. Within this context, Sui’s exploration of Daoist grotto-heavens, Guo’s handmade book reminiscent of traditional Chinese scroll paintings, and Zeng’s large vertical compositions embodying “armchair travel” all contribute to the curator’s aim: “to employ distinctly Chinese perspectives and lived experience as a critical framework for engaging with global discourses on geography, geology, and geopolitics.”[4]

Installation views of the exhibition “Photographic Geomancy”, 2024, Guangdong Times Museum, Guangzhou

Courtesy Guangdong Times Museum

The second chapter “Geological Perception” delves deeper into artists’ multifaceted integration of mountains with geography, particularly at the level of specific life experiences. Due to the scope of this essay, I will only provide one example: Xiaoyi Chen’s The Visions of Karma (2024) was a video work based on her research into mining remnants in the Hengduan Mountains region. Cao Minghao and Chen Jianjun, an artist duo long practicing socially engaged art and having become known for establishing connections and collaborations with communities in their investigative and creative areas, made a comment on Xiaoyi Chen’s “image-scanning” style of artistic practice about the Hengduan Mountains since 2018. They noted that, unlike their emphasis on “communication and collaboration,” “Xiaoyi interacts with nature and mountains in a very intuitive, spiritual, and literary way… Normally, we might think communication relies on language and words, but Xiaoyi truly has the direct ability to communicate with nature and receive feedback from it.”[5]

Installation views of the exhibition “Photographic Geomancy”, 2024, Guangdong Times Museum, Guangzhou

Courtesy Guangdong Times Museum

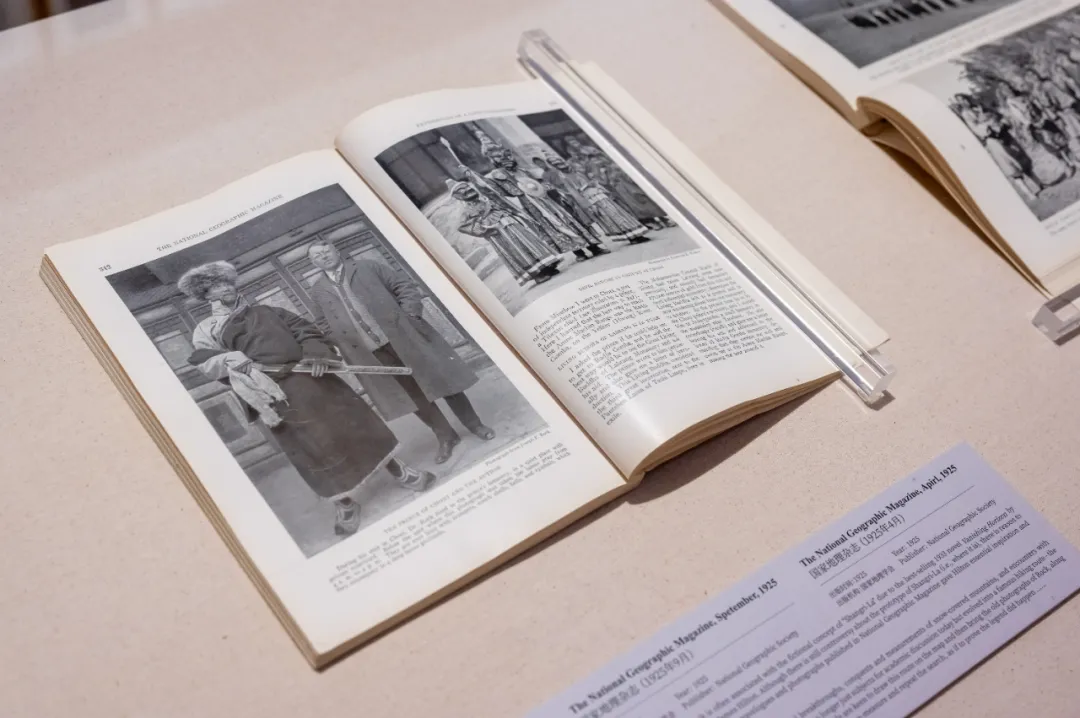

This “exhibition on paper” will conclude with “Between Nakhi and Tibetan: Joseph Rock’s Ethnographic Photography in China,” an exhibition held in spring 2024 at the Xie Zilong Photography Museum in Changsha. Curated by photographer and scholar Degjinhuu, the exhibition featured over 500 photographs, videos, and archival documents related to Joseph Rock, an American plant hunter and researcher of Nakhi people, active in Yunnan regions centered around Lijiang in the early 20th century. Given Degjinhuu’s research interests in visual anthropology and ethnographic photography, the ethnographic nature presented in the exhibition aligns more closely with the anthropological definition—a holistic representation and documentation of a specific local ethnic group. The curator specifically emphasized it, striving to showcase how Rock, from the 1920s to the 1940s, acted as a representative from the more “advanced” West, conducting scientific and cultural research in the “underdeveloped” hinterlands of the East.

Installation view of the exhibition “Between Nakhi and Tibetan: Joseph Rock′s Ethnographic Photography in China”, 2024-2025, Xie Zilong Photography Museum, Changsha

Courtesy Xie Zilong Photography Museum

Rock and his local teammates traveled through the mountains and forests of southwest China. Their journey began in northwestern Yunnan, where his work focused primarily on Dongba culture, and extended into Sichuan, Gansu, Qinghai, and Tibet, where Tibetan Buddhism was central. Some of these exhibited photographs are portraits Rock took about or with his teammates. In one of those group photos, Rock stands in the distance, near the center of the frame, but with his hands on his hips, he is still less striking than the local person in the middle ground, also dressed in white, comfortably reclining on the grass. If we compare this photo to the famous image in the history, an anthropological photography documenting Malinowski with Trobriand Islanders (likely taken by Billy Hancock, a pearl merchant active in local areas, circa 1918), we find that, despite operating in a similar era, it is Rock, considered not an anthropologist, who appears to have established a relatively more equal relationship with the local people.

Installation view of the exhibition “Between Nakhi and Tibetan: Joseph Rock′s Ethnographic Photography in China”, 2024-2025, Xie Zilong Photography Museum, Changsha

Courtesy Xie Zilong Photography Museum

Of course, we cannot ignore the historical limitations evident in Rock’s photographs, as some of these images betrayed traces of his Western sense of superiority, epitomized in a scene where a group of lamas gathered around a gramophone, turning their gaze back at Rock who was holding his camera. Such intentional contrast between the “primitive” and the “modern” also appears in Robert Flaherty’s documentary Nanook of the North (1922), in which the director instructed the Inuit protagonist who was already familiar with gramophones to feign curiosity toward Western technology. Rock’s depiction of snow mountains similarly adopts a Western approach to the sublime. Whether capturing Mount Jampayang, one of the three sacred peaks, or Mount Gongga, he emphasizes the intricate textures and tactile contrasts between ice and rock. The towering peaks pierce the sky in his compositions, evoking a sense of majesty and indestructibility. This visual language reflects the Western sublime’s preoccupation with awe, finitude, and human insignificance in the face of nature. Here, nature is rendered as a site of transcendence and spiritual elevation, which stands in stark contrast to the Eastern view of nature as intimate and harmonious.

Joseph Rock, A Group of Lamas Listening to Music on a Phonograph, 1926, Qinghai

© National Geographic Society

Notes

[1] Zhang Zimu, Guo Jing, “The Ecological and Archival Nature of Rural Images—An Interview with Guo Jing,” Chinese Independent Film Review, Issue 4, 2022, p. 292.

[2] Chao Jiaxing, Liu Yujia, “Liu Yujia on Reality and Fiction in Travel Photography,” ARTFORUM Chinese Edition WeChat public Platform, July 14, 2023, https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/3GSG_oIV-BidRDylgb08qg.

[3] Chen Licai,“A Darkness Shimmering in The Light—Flowing Fusion and Regeneration,” 2024, unpublished manuscript.

[4] He Yining, “Curatorial Practices at the Intersection of Geography, Geology, and Geopolitics,” Chinese Photography, No. 8, 2024, p. 131.

[5] Cao Minghao and Chen Jianjun, “Future Greats: Xiaoyi Chen, selected by Cao Minghao and Chen Jianjun”, ArtReview China WeChat public platform, September 18, 2024, https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/ePlCoqmV5yIIUEog5YsfZg.

Curation and Text by Yang Yunchang

Translated by Edel Yang

Yunchang Yang is a researcher and lecturer in the Department of Sociology at Peking University. He previously held a postdoctoral position in the School of Arts at the same university. He received his undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral degrees in anthropology from Sun Yat-sen University, the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), and University College London, respectively. Yang teaches courses in anthropology, cultural studies, and anthropological theory. His research interests include social anthropology, the anthropology of art and image, and modern and contemporary Chinese visual culture, with a particular focus on the notion of “amateurism” in everyday life and fieldwork practices in contemporary art.