Moving Mountains: Su Yu-Xin’s “Searching the Sky for Gold” and Contemporary Poetry of the Asian Diaspora

| December 5, 2025

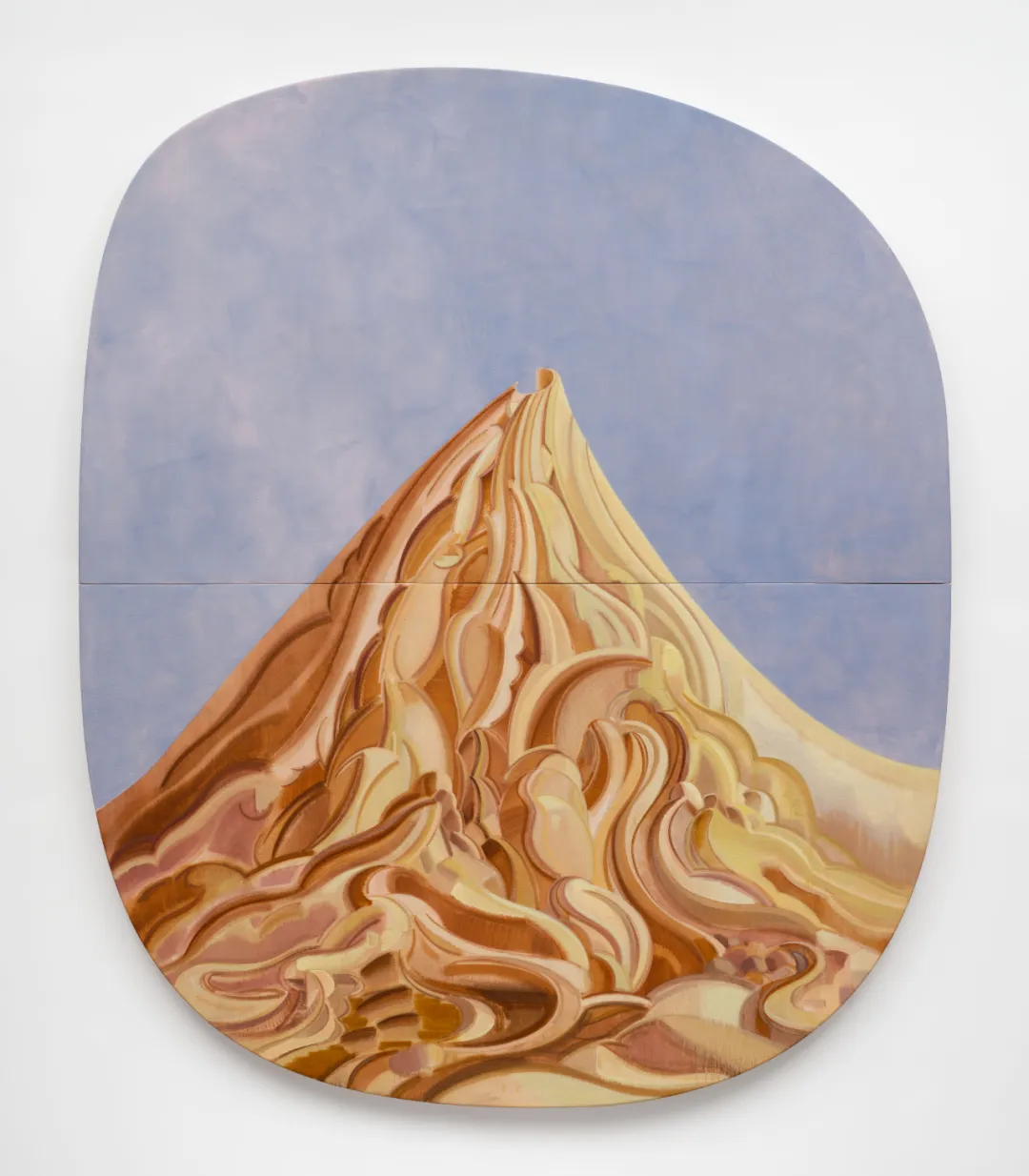

Dust Crown (Mount St. Helens) #2, 2024

Helenite, orpiment, titanium dioxide, halloysitum rubrum, woad lake pigment, seaglass, black volcano rocks, ceramic glaze and other hand-made pigments on flax stretched over wooden frames and wooden stands, 245 × 155 × 5.6 cm

Courtesy the artist

Su Yu-Xin’s first individual exhibition outside Asia at the Orange County Museum of Art, “Searching the Sky for Gold,” features paintings of drizzles and mighty fires, catalogues of earth-derived colors, and studies of smoke and clouds. The Hualien-born axnd Los Angeles-based artist depicts both shores at rest and mountains undergoing weather and geological events. The landscapes chosen by Su are not by themselves widely recognizable. I, for one, rely on the paintings’ titles and descriptions to identify where the coasts and mountain ranges are. She captures un-iconic sites and focuses on elemental phenomena so that in lieu of locations, the many manifestations of classical elements (i.e., earth, water, fire, and air) become the show’s motifs and distinguishing features.

The paintings in “Searching the Sky for Gold” share the aesthetics of Asian American and diasporic Asian poets in the U.S. who in recent decades, write in response to historical atrocities. Across pages and canvases, the recurrent smoke-clouds, rings of dust, and licks of flames are entangled with the labor and persecution of Asian immigrants on the colonized land of America. Testimonial poetry in particular cycles through similar images and metaphors rooted in natural resources and environments. The way in which many poems center on islands and rural areas, where people were stranded or displaced, has resonances with Su’s paintings of mountains, which often seclude and position subjects at the dead-center, like portraits. The imagery seems, in a nutshell, particularly Asian-coded.

Su Yu-Xin draws the title of her exhibition from that of a nonfiction book. A self-published paperback, Gold Mine in the Sky: A Personal History of the Log Cabin Mine recounts the family stories of the author, Frank Cassidy Jr., and relays the history of a now-defunct mine, for which prospectors first filed a claim in 1890. To claim the mine as a “gold mine in the sky” is waxing metaphoric, but to reach the mine situated at 3,000 meters altitude, miners indeed looked toward the sky when they hiked up the steep Tioga Canyon, lugging supplies and equipment on horseback. According to Cassidy, the Log Cabin Mine was for a time the largest gold mining operation in California. Profits for its stakeholders had once skyrocketed. The author’s nostalgia for the luck and pluck of a bygone glory translates into the book’s title. Su, on the contrary, does not sentimentalize her works. Instead of hewing to her reference point, she reframes the exhibition’s name to “Searching the Sky for Gold” and contextualizes her paintings within a more composite historical narrative.

Throwing the verb search into relief, Su Yu-Xin’s juxtaposition of sky and gold evokes the tireless search for fortune and the struggle to obtain jobs. The paintings themselves outline travel and immigration routes from Asia: they portray Mt. Kuju in Japan, Mt. Merapi in Indonesia, salt caves on California’s coast, an underground fire in Utah, the Trinity Site in New Mexico, etc. and utilize local materials sourced on location. Thus, the exhibition lends itself to speaking about the waves of East Asian immigration to America throughout the latter half of the 19th century. A close reading of the title will reveal that with “Searching the Sky for Gold,” Su seems to focus the lens especially on the experience of Chinese-speaking immigrants.

For the mountains, a thousand arms / to scale the rocks, a thousand hands to lose / in blasts.

— “千 / Thousand,” Paisley Rekdal

The poet Christine Kitano writes that “sky country,” which derives from the Korean word for heaven, was “often used by potential immigrants to describe the United States.” Whether or not the idiom “sky country,” given its Korean origin and Christian connotation, was adopted by emigrant Chinese workers to talk about their destination, the workers became closely associated with the word sky when they arrived in America, as the American society referred to them as “celestials” in newspapers and common parlance. The term is said to stem from the archaic name that the Chinese Empire gave itself: the “Celestial Empire” (天朝). To the Chinese-speaking population now and then, “celestials” might not come across as derogatory. It is in fact possible to construe the name as the complete opposite. Not only does it have resonances of the honorific title “Son of Heaven” (天子), which would equate the workers to imperial descendants, but it sounds like a way of invoking the gods and goddesses in Daoist and folk Chinese beliefs, who hold court in heavenly palaces.

Yet, there is little doubt that “celestials” was devised to be pejorative and that Chinese immigrants at the time would interpret it as such. The term was used to stereotype the Chinese as addicts engulfed in clouds of opium smoke. In essence, it alleges that all Chinese smoked opium. It accuses—of course wrongly—the Chinese in America for doing nothing but smoking pipes in dens and spreading the pernicious habit to susceptible white Americans. In an 1880 news article captioned “Celestials Corraled (sic),” the reporter writes,

The celestials who occupied [the] bunks looked largely at their visitors in a stupid, dazed sort of way that betrayed consciousness by no intelligence. The fumes of the place were dreadful—the whole atmosphere was laden with the sickly smell of the drug.

Naming opium smokers “celestials” traffics ritualistic and religious imagery, where people burn and sacrifice incense to deities and spirits in places of worship. In short, it is a sacrilege. For Chinese culture especially—which believes those who command clouds and ride on fog (腾云驾雾) are often immortals and those who know the Way (神仙和得道之人)—the name insults its belief system by conflating the enlightened and the condemned and furthermore, satirizes smokers by laying bare just how far they have strayed from the righteous path.

On the other hand, gold was the principal object that Chinese emigrants hoped to excavate and trade on foreign soil. The California gold rush picked up steam in 1849. When it started to die down a few years later, the diverse group of gold diggers known as the “forty-niners” migrated north to states like Washington, chasing after rumored gold. Chinese gold miners distinguished themselves through their resourcefulness that later, attracted envy and hatred. At the sites already raided by their white counterparts, who panned surfaces and snatched easy nuggets, Chinese miners “…dug more and dug deeper. They used wooden sluicing contraptions called ‘rockers’ to skim gold from gravel by washing it through quicksilver (mercury) and rocking it back and forth, and they found what the white miners had missed.” In a similar fashion, Su Yu-Xin sweeps the mountains in Hunan, Arizona’s salt flats, and coastlines of Taiwan and California, looking for ore rocks, precious stones, shells, clumps of clay, and organic remains that others have overlooked. She chooses to glean, rather than planting and harvesting. Her ability to gather leftovers wherever she travels highlights the way in which nowadays, there is not a single stretch of land that has not yet been touched or extracted from. This account of planetary extraction parallels the history of the exploitation of Chinese immigrant labor. In a poem that appropriates language from an archival letter, the poet Paisley Rekdal re-enacts an emblematic description by an American supervisor of Chinese workers toiling through American mountains:

…they shall not walk

on our sidewalks or marry

a white man or woman all this

and they shall keep the Negro

steady they are quiet

good cooks good

at almost everything

they are put at indeed

the only trouble is

we cannot talk to them

Before the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882—the first exclusionary law to target an ethnicity—Chinese immigrants were treated as laborers stripped of basic rights, whose sole purpose was to work and keep another race in check. “Good / at almost everything / they are put at”: the line breaks imply scrutiny that is both judgmental and wary. Albeit skilled and reliable for the most part, Chinese workers were accused of not being able to exercise independent thinking; instead, they must be “put at” and directed to tasks. Worst of all, in some Americans’ eyes, not being able to speak English meant that the workers could not command language. Therefore, “Searching the Sky for Gold” communicates a euphemism: settlers looked for fine, valuable manpower, and it landed in their lap. When American companies recruited “celestials” for the excavation of natural resources on stolen land, they used Chinese workers as tools or put simply, wrested the labor out of the human. In reference to this context, the exhibition title brings various levels of extractive practices such as gold digging and labor abuse to bear on the paintings.

Nothing / so linear as human / ego and desire, while the past //

turns and returns, spirals / like these pelicans journeying / over the red //

waters off Rozel, streams / of purple; yucca rimed / with pustules of dust.

— “来 / Journey,” Paisley Rekdal

Dust Crown (Mount St. Helens), 2024

Helenite, sea glass, pink coral (tubipora musica), pastel made from volcanic ash, azurite, sulphur, white marble and other hand-made pigments on flax stretched over wooden frame, 260 × 150 × 5.6 cm

Courtesy the artist

In stark contrast to invasive mining activities, what happens at the mountains on Su Yu-Xin’s flax canvases is natural, devoid of human presence. Against the background of human history, these paintings reorient the focus to geologic processes and resituate the mountains within their own changes and movements. Both Dust Crown paintings depict Mount St. Helens amid explosive eruptions: if one painting corresponds to the real eruption that occurred early morning one day in May of 1980, then the other, set at night, seems to be a fantastical rendering of the event. For Dust Crown #1, Su made pigments by grinding Helenite—glass gems fused from the 1980 eruption’s volcanic ash and rock dust—and used them to paint the crown of dust a cross of dark green and blue.

Despite being named a crown, the mixture of volcanic ash and gas does not merely sit atop the fumarole; strands of it run along the mountain, submerging the exposed peak. In terms of color, too, the mass of airborne dust is indistinguishable from its reflection in the adjacent lake, which is a little more than visible at the bottom of the canvas. The “dust crown” dominates the painting. Its cool tone resists any association with the red-hot cloud from a nuclear blast (which draws out a different Asian American history), despite the two’s structural resemblance.

The edges of this painting are blurred or dulled—its wooden frame, for example, has rounded corners. As mentioned above, the divide is seamless between the massive cloud of smoke and the pyroclastic flow, which is currents of gas and debris pouring down the sides of a volcano. Here, Su reverses the course of the flow, which as a result, seems to spew directly from the ground. What happens is confusion over where the smoke is going, inside or outside, a confluence of directions. Assuming the form of spirals, Su’s lines—drawn with pastels made from volcanic ash—burgeon like fiddlehead fern. They curve inward, as if to contain themselves.

Dust Crown #2 consists of luminous bodies in different sizes. The vent and nimbus-like cloud of volcanic gases appear to be backlit, as does Mount St. Helen, which is colored in by neat strokes that give the mountain almost reflective surfaces. Radiant stars dot the sky and crown the eruption. The pyroclastic flow cascading down to the ground lights up the horizon. Nothing else stands in the surrounding space.

This fictional depiction, even more so than the other Dust Crown, restores steam and smoke to natural settings and untangles the motifs from portrayals of human strife. As evidenced by Paisley Redkal’s poetry collection West: A Translation, images of smoke are central to accounts of immigrant labor in the westward expansion of the U.S, which included the construction of the first transcontinental railroad. Completed in 1869, the railroad connecting eastern railway networks to America’s west coast was built in large measure by workers from China. Imagining puffing smoke, Rekdal writes, “What is a train / but the self once yoked to terror loosed / inside a force that glides / on heat and steam?” She speaks of rock blasting, smoke that provokes memories of war, and “windmilling blows” that stir up billows of dust. Dealing with the same thematic concern, Su nevertheless engages with Chinese workers’ plight obliquely. As an alternative to representing historical trauma, she traces the roots of loaded motifs to their origins in nature. She points to a rupture in a volcano that despite its disastrous scale, has closed up. The future proves that wounds, real or metaphoric, can heal. And the landscape that contains wounds, where they are evident, can be sites of memory. Su’s paintings capture a transitional phase that gestures toward both metamorphosis and commemoration.

Another work of an active volcano, The Birth of an Island (Niijima, South of Iwo Jima), views eruption as synonymous with birth.

The Birth of an Island (Niijima, South of Iwo Jima), 2024

Malachite, gofun, pink coral (tubipora musica), cochineal dye, california soil and ochre, black volcanic rock, iron dioxide green, zinc powder, plastic and other hand-made pigments on flax stretched over wooden frames and wooden stands, 240 × 160 × 5.5 cm

Courtesy the artist

Su paints the waves using pigments crafted from malachite, reefs, and oyster shells in green, pink, and white. The pink color standing out among swaths of green and peeking through resembles the coal seams, as seen on faults, in mountainous areas. Yet, unlike the lines along faults, the waves’ lines here signal flux and turbulence. Although winds are implicit in the painting, they do not affect the whirl of volcanic fumes. The smoke ascends unwaveringly skyward. It signifies a kind of escape that eluded the emigrants once detained at the Angel Island Immigration Station, a customs and inspection facility that processed immigration requests. On Angel Island, which is just a ferry ride away from San Francisco, individuals and families waited for sponsorships and security clearances in extended periods of confinement.

Compositionally speaking, the painting’s smoke is made from shells in powder form, and so it is as if the shells ascend, too. Like the “Dust Crown” series, The Birth of an Island takes interest in the movement from earth’s crust up into the sky—as rocks in the mantle and lower crust melt into magma and become ash in volcanic smog—dedicating significant space to depicting the atmosphere. The smoke rises to heaven, becoming celestial. The painting reclaims the contested word “celestial” and re-situates it within the realm of mythology, where creatures are sky-bound, and tectonic activities oracular. In creation myths, the workings of nature remain partially inexplicable and are yet to be deciphered.

moths may orient celestially or / are thrown off by our light

— “Altar,” Claire Hong

Not in keeping with her practice of putting much thought into titles, Su Yu-Xin does not name the pigments she made from scratch. When it comes to colors, she chooses not to exercise the power of naming, a political act that the poet Claire Hong examines in her book of poetry Upend. More often than the precious metal, the name gold denotes a color, a measure of value, or something that is the finest of its kind. Although gold is a variant of yellow, and that in the 19th century Chinese workers proved themselves as superior labor—cheap, willing, and capable of enduring so much physical labor that it astounded their employers—Chinese people were never compared to gold but caricatured in American diction as having a yellow skin tone. In a poem entitled “How Yellow Men Steal Our Yellow Stuff,” Claire Hong writes, “gold named for / yellow dawn / neutron stars / sank in molten earth / so malleable it / can be smashed / transparent.” The stanza points out the many things being named after gold, and none of them relates to the Chinese ethnicity, which was always marked with yellow. The two colors were treated as non-fungible along racial lines, and gold is the unattainable status used to bar Chinese from recognition. At the same time, Hong’s poem directs readers to consider the double bind of gold: despite gold’s desirability, malleated gold becomes transparent. Adapted into the fabric of American construction, early Chinese immigrants were so well-adjusted that they were exploited and then promptly overlooked by the nation in urgent need of them.

Engaging in a series of juxtapositions, Upend explores the relationships between names and rights, between industrialization and erasure. In the first poem “Find and Explore,” Hong places names of cities in California side by side with equally absurd names of the colors manufactured by Sherwin-Williams, a multinational company that specializes in paints. The city of Chino—its name cognate with words China and Chinese—is listed alongside colors like “Olde World Gold 7700.” Likewise, the city of Indio, with the word indio referring to Indigenous peoples of the Americas, is catalogued next to a paint color called “Well-Bred Brown 7027.” These juxtapositions reveal how municipal and commercial names are far from being politically neutral. The act of naming carries with it the capacity to impart value judgments.

Image from Upend (2020) by Claire Hong, page 71

Against oddly specific names of places and paint colors, Hong offers the names by which her maternal grandfather and great-grandmother were once identified at the detention center on Angel Island. While Hong’s maternal grandfather was assigned “No. 135,” her great grandmother was crassly labeled “Unknown <Indian>.” The poet writes,

the paint company Sherwin-Williams has over forty names

to describe any shade—brown to yellow to grey—as gold

their logo reads “cover the earth”

see paint blood drip

down earth head

land pulled off at the crown

Hong gives two examples of the power of naming: to call a color clearly not gold “gold” to upsell the color; to deny someone a name to degrade them. Names are also derivative and mere placeholders for the absence of power: it is possible to come up with “over forty names” for one color but hardly possible to find a person from recent history through their name. The irony is that anyone can look up a specific color in high quality images on the Sherwin-Williams website with a few clicks. One can pinpoint with alarming precision the shade of some plaques and photos as “Relic Bronze 6403.” Yet, to locate details about a dead relative, one must leaf through documents and can only obtain blurry photocopies for one’s own record. Hong prompts readers to notice not only Sherwin-Williams’ industrial processing but also its logo that reads “cover the earth.” The Ohio-based paint company had been industrializing and privatizing colors through copyrights since the 1860s. Their business strategization was concurrent with the massacres of Chinese and Native Americans during the onslaught of American settler-colonialism, when state governments awarded money for Native Americans’ scalps. In a way, the paint swatches of earth-toned, “gold” colors resemble a macabre collage of scalps. It is also plausible that a swatch like “framed Harvest Gold 2858” can function as an altar for some whose ancestors were erased in the records.

The Map of Mine and Other Things, 2024

Pure copper, chalcopyrite, azurite, pure silver, blue coral (heliopora coerulea), malachite, gofun, copper oxide, soil, acrylic paint and other hand-made pigments on hand-shaped wood, 26.6 × 19.5 × 4.25 cm

Courtesy the artist

The names of Sherwin-Williams paints operate through abstraction. They transform colors from subjective experiences of light entering the eye to combinations of nouns and showy adjectives. Such names impose on someone who purchases, say, “Independent Gold” or “Kingdom Gold,” an identification with American democracy or British monarchy. As opposed to bearing overdetermined names that obscure their ingredients, Su Yu-Xin’s pigments are known by the raw materials, some of which—like Helenite—can even be traced to their places of origin. The materials are the colors, and vice versa. The name and the thing are the same.

Changeable and often volatile, Su’s pigments such as the one produced from sulfur are anything but standardized. Also, by not using oil paints manufactured by popular companies in the market, the artist opts out from oil painting’s dominant vocabulary and chooses instead to develop her own.

Using sulfur, soil, and bleached coral bones, the painting Noon Break (Mount Merapi) offers a bouquet of gold that, instead of splayed on a disembodied palette, represents a living body. The different gold colors cohere to reflect the source of light coming from the East. At the center, increments of gold tangles convey the mountain’s rocky surface in detail. This treatment of colors seems to stem from the coloring practice used in shanshui paintings, which Su adapts to show a sunny environment with high visibility.

Noon Break (Mount Merapi), 2024

Sulphur, soil, bleached coral bone, blue coral (Heliopora coerulea), halloysitum rubrum and other hand-made pigments on flax stretched over wooden frame, 213 × 252 × 5.6 cm (213 × 126 × 5.6 cm each)

Courtesy the artist

In the Chinese landscape tradition, the use of colors including blue (青) and green (绿) “demonstrates a strong sensitivity to light,” Su writes in her meditation on colors. As an example, she discusses how painters designated blue pigments made from azurite for a mountain’s shaded parts and green pigments made from malachite for sunlit parts. In nature, azurite and malachite often co-exist on one ore rock “like the bright and dark sides of one mountain.” For the tropical mountain, Su swaps the symbiotic blue and green for shades of gold.

In California taught to pick a poppy / is illegal taught to fear / its gold in synonyms and borders

— “Diamond Scraps of Southeast Alaska, Northern California, Northwest New Mexico,” Claire Hong

As the same motifs and mountains haunt “Searching the Sky for Gold,” the volcanic cloud that characterizes Su’s paintings of Mount St. Helens also appears in Heaven’s Sigh (Mount Merapi) and lingers on top of the mountain. The smoke exhaled by the active volcano is composed of two parts with little transition in between: the part closer to the vent is projectile, like the orbit of a star, and as the smoke disperses, the second part of it is depicted as a chain of small whorls. The trajectory changes from sharp and clearly delineated to loose and ethereal. The thin cloud that seems to envelope the mountain eventually dissipates and merges into the background. In the painting, Su used Japanese mineral pigments (iwa-enogu) typical of nihonga and ground pyrite, which is nicknamed “fool’s gold” for its resemblance to gold, to obtain its powdered form. The choice for materials recalls Claire Kageyama-Ramakrishnan’s poem “Collage/Bricolage: Fragments of Truth” on the Japanese internment camp in California.

In response to Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, U.S. Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt signed the Civilian Exclusion Order No. 69, which authorized military agencies to relocate hundreds and thousands of people of Japanese ancestry who resided on the West Coast. The order in effect deported civilians and corralled them into prison camps. The internment has been a cultural wound for generations of Japanese-American descendants, which Kageyama-Ramakrishnan likens to “[a] persistent nagging, / the ache or itch / inside the skull, skirting among / a swirl of cells and slippery tissue.” If wounds manifest in the landscape, and the landscape testifies to them, then the curling smoke in Su’s artwork approximates such a wound. Alternatively, the “swirl of cells and slippery tissue” as seen in the painting gives form to the wounded and deceased, who rise to the sky, freed and carried by the wind. Besides mineral paints from Japan, Heaven’s Sigh (Mount Merapi) incorporates pyrite or more colloquially, “fool’s gold.” The logic is that only a fool would mistake pyrite for real gold, but the frenzied determination to find gold could lead someone to claim the lookalike as the real deal. In short, longing can make a fool out of anyone, and foolery may be as simple as getting tricked by one’s own mind. In her poem, Kageyama-Ramakrishnan describes a similar experience of being beset by longing:

…with clouds casting

bruised shadows over the wounded

valley, the area outside the camp

bearing the wreckage of erupted

volcanoes, scorched earth,

aqueduct that had drained

the land of its water.

When they looked at

Mount Williamson they saw an umbrella

and upside down fan—Mount Fuji…

In the “foolish” act—of finding the volcano that symbolizes Japan in a mountain that borders the concentration camp—is the political prisoners’ yearning for a semblance of home. Mount Williamson is a fool’s Mount Fuji. Who else, being incarcerated, would dream of a place far away across the ocean? And isn’t Mount Merapi, in a similar vein, a fool’s Mount Williamson? Like the poet, I, too, have been thinking about California through the lens of hostages-in-war even when Su specified that her work portrays Mount Merapi of Indonesia. For me, the poem and the painting complement one another. With the knowledge of Japanese Americans’ internment in mind, I see the painting’s shadows as bruised, its surface burnt as a direct result of natural disasters or the scorched-earth policy. My desire to mourn the past has gotten the better of me.

Heaven’s Sigh, 2024

Various colors of volcanic rocks, pyrite (fool’s gold), ochre, soil, oyster shell fossil, iwa-enogu, sandstone and other hand-made pigments on flax stretched over wooden frame, 252 × 213 × 5.6 cm (213 × 126 × 5.6 cm each)

Courtesy the artist

In painting Heaven’s Sigh [Mount Merapi] as well as Noon Break [Mount Merapi], Su Yu-Xin chooses a vantage point that is level with the peak of Mount Merapi, so that the rest of the mountain extending all the way to the ground is cropped out of the canvases. The paintings’ composition isolates the mountaintop and provokes a sense of isolation—along with the attendant hyper-fixation on certain ideas and imagery—that Christine Kitano characterizes in her sequence of poems on the Topaz Concentration Camp in Utah. The speaker of Kitano’s poem “I Will Explain Hope,” a prisoner at the camp, laments that “…elsewhere, lives go on / making marked progress but we remain / stranded within a stalled circle…” The psychological harm of imprisonment, solitary or collective, is that one becomes consumed by one’s own subjective experience and eventually loses perspective. It certainly is the prisoner’s bias to think that progress happens everywhere else. The imprisoned speaker continues to reminisce, at the sight of what could be fireflies:

My mother would say the fireflies

are the lights of soldiers killed in a war far away,

their spirits now wandering the earth in search of home.

But these are not fireflies. How to say fireflies

don’t come to Utah, how to say how close, or far,

we are from home?

Though they may be going extinct, fireflies do live in Utah. Here, the speaker’s understanding—taking after the confined speaker herself, who is cut off from the outside world—comes to be defined solely by her sightings of fireflies in Japan and her knowledge of Japanese folklore. The poetic logic is thus: fireflies are the spirits of Japanese ancestors, and the ancestors cannot be in Utah; therefore, what is seen in Utah cannot be fireflies. The fact that people tend to perceive the world exclusively through lived experiences, which institutions encourage and profit from, is an observation that Su draws on in her selection of materials. In an interview, she notes that she has often spotted on the coasts of Taiwan many species of mollusks that are labeled as endangered or extinct in California. Regarding creatures of the unmapped oceans, conclusions about extinction status often seem subjective and inconclusive, Su says, for no one can actually count and enumerate what lives in the sea. By painting with coral bones and shell fossils that may well be protected species in some places, Su challenges forms of knowledge-making that cannot overcome the constraints of location and cultural background.

I’ll still be blasting rock, this time / in the coal mines.

— “Letter Home,” Teow Lim Goh

On May 10th of 1869, workers bridged two railroads—one hailing from coastal California and the other, midwestern Nebraska—and thus finished building the first ever railroad that spanned the continent of North America. The place where the track’s last spike was hammered into place is in Northern Utah. There, the men who had worked closely alongside each other for quite some time parted ways, in pursuit of the next opportunities. Many of these workers came from China. Despite their hard work on the railroad, they were not paid enough to finance their travel home. Consequently, some made do with working jobs at mines nearby. Some, responding to out-of-state job advertisements, rode the train beyond Utah to a semi-arid region in Wyoming. The coal mines at a town called Rock Springs called to them, and the workers toiled. These miners at Rock Springs were perhaps the best known in U.S. history of all the Chinese railroad workers who went on to become miners, because of the Rock Springs Massacre that happened on September 2nd, 1885, where at least 28 Chinese immigrants were lynched.

Using a series of dramatic monologues and free-indirect speeches in her poetry collection Bitter Creek, Teow Lim Goh chronicles the events that led up to the brutal murders in Wyoming. Goh begins her narration with the ceremony celebrating the transcontinental railroad’s completion in 1869. She revisits the 6 years of hard labor on the railroad and writes of the way workers

…climbed

the deep ravines and rugged granite walls

of the Sierra, working through hot summers

and brutal winters, blasting tunnels in

the stubborn rock…

The fourth line in the excerpt juxtaposes “brutal winters” and “blasting tunnels,” creating the impression that the building of tunnels happened predominantly in wintertime and not so much during summers. The line implies railroad companies’ poor planning. Workers were set on the task in winter, which is arguably the worst season for tunnel construction. Wet or frozen ground makes blasting and excavation punishing. By contrast, building tunnels on summer days would limit the workers’ time being exposed to sunlight, and in the summer, digging through mountains would provide the benefit of shade. Goh’s line suggests that when the sun was at its most grueling, workers were assigned to outdoor operations such as laying tracks. Companies did not adjust the schedule for weather conditions or prioritize workers’ well-being over their own convenience.

Heart of Darkness (Underground Burning, Utah), 2024

Realgar, orpiment, sulphur, cinnabarite, soot, china fir charcoal, purple shale, black tourmaline, red agate, organ pipe coral (tubipora musica), soil, hematite, lapis lazuli, amazonite, red garnet, dupont titanium dioxide and other hand-made pigments on flax stretched over wooden frame and wooden stands, 240 × 160 × 5.6 cm

Courtesy the artist

Another example in which human involvement worsens the state of things lies in Su Yu-Xin’s “Heart of Darkness (Underground Burning, Utah).” The painting lets viewers in on a sight beyond human reach: an underground fire that is blazing in the coal seams as we speak and has been burning ever since it was started by either a mining accident or spontaneous combustion. What the fire looks like underground is anyone’s guess; all that one can safely see is the smoke climbing to the ground level. Although the speculative fire painted by Su may have happened naturally, it is still fueled by local and global human activities, which bring about rising temperatures and desertification. Because underground fires feed on air through fissures and cracks in the ground, drier soil leads to more air supply and thus makes the fires stronger and even more expensive to extinguish. To accentuate their thirst for oxygen, the exhibition text analogizes the flames in “Heart of Darkness (Underground Burning, Utah)” to serpents, whose tongues “snatch at air.”

The painting also serves as a metaphor for the type of work environment that Chinese miners had to endure in Wyoming. Speaking of a coal miner in her poem “Landlocked,” Teow Lim Goh writes: “All day he crouches // in a sweltering room, picking at seams / for nuggets of coal…” The room—an area inside the mine where coal is extracted—is suffocatingly hot, as if there is a fire burning nearby, which exhausts the air inside the mine. Like he is vying for air with fire, the man must feel short of breath because he has been “crouching all day.” And in the same way that Su’s wooden frames and stands are carved out, a room in the mine is dug into being and attains its perimeters only when miners finish picking.

While the atmosphere within mines might be stuffy, the climate outside was frigid. Goh extrapolates the opposites of “hot summers” and “brutal winters” on the transcontinental railroad to mining work. When she writes of Rock Springs itself, which she describes as “a desert of broken rocks,” the mining town appears cold and desolate. “Carpenters build huts all morning, / a makeshift Chinatown on the icy ground.” This description corresponds historically to the segregation of Chinese immigrants into a quarter of shabby, drafty wooden structures in the city. Goh zeros in on a moment in time when the ground was frozen and easily gave way to pressure. Her word choice icy bespeaks the political climate and tension between the Chinese and Europeans. Prior to Chinese workers’ arrival, white miners in Rock Springs had gone on a strike over their inadequate pay against the owner of mines in the region, the Union Pacific Corporation. To break and dissolve the strike, Union Pacific seized the opportunity to take advantage of Chinese workers, who were stranded in the U.S. and desperate to be employed after completing their railroad work. The company sent workers via train to Wyoming en masse. Willing to work for a low wage, Chinese miners came to replace their white counterparts and over time, drove them out of the workforce. This exacerbated the latter’s resentment on account of racial and cultural biases. From white workers’ perspective, the newcomers were to blame for everything—not only their moot strike but also the subsequent unemployment crisis.

Tension begets addictions. “Whiskey // burns his throat, drowning / the ache of his abode,” Goh writes in a poem centering on one miner. The rhyme between throat and abode neatly wraps up the sentence the way the miner thinks whiskey can alleviate his emotional pains. There would never be an end to his thirst for alcohol, as much as the fire in Su’s painting is literally and figuratively inextinguishable. The fire demonstrates, too, that a mine can become a hellish place. In the poem “China Mary,” a Chinese witness relates a horrible explosion at a mine and bemoans the casualties, her countrymen, whose bodies “are still buried in the rubble / too dangerous to reach.” Once an accident takes place, the coal mine will turn into a pit of long-lasting fire, and bodies become firewood. Ultimately, “Heart of Darkness (Underground Burning, Utah)” can be read in terms of a memorial to the Rock Springs Massacre, which exists in a limbo much like underground fires. Legally speaking, the massacre’s victims and their families never received any personal restitutions, whereas all the perpetrators lived the rest of their lives unpunished. Retributions are much warranted, however. In addition to lynchings, many died by arson after a mob set Chinatown aflame. The fire also limited people’s access to the guns they had in store for self-protection. The poem “Chinatown Burning” elaborates on the horrific details: “The flames lap at the stashes of gunpowder / that miners keep beside their tools. Explosions / rattle the streets and echo past the cliffs.” Paying no mind to the increasingly uncontrollable damage, “[the crowd of bystanders] cheers on each blast.” In this last poem of Bitter Creek, Goh continues with the present tense that characterizes the rest of the book, staking a claim for the hate crime in our present cultural landscape.

Before the lava cooled / we could sing. // Before the beaches died / we could chant prayers.

— “Paradise,” Janice Mirikitani

A poem set in Hawaii, Janice Mirikitani’s “Paradise” opens with the following four lines: “Before the lava cooled / we could sing. // Before the beaches died / we could chant prayers.” Even though they follow the same structure, the two sentences differ tonally: the first communicates resilience or the ability to quickly recover and find solace in songs in the wake of an eruption; the second, on the other hand, is poignant. It mourns the collapse of ecosystems and a social function. In other words, “we” could no longer pray because beaches have become too polluted. The poet uses one grammar to convey two completely different tones. The same goes for the paintings in “Searching the Sky for Gold.” Su’s singular style encompasses various thematic concerns and encourages different readings, just as her colors are variegated and prismatic. I suggest with this essay one way to experience the paintings by staging a conversation between them and contemporary Asian American poetry. Owing to my emphasis on mountains, I will refrain from discussing the coastlines in “With or Without the Sun #3 (Coastal Road on the East Side of Taiwan)” and “Salt Caves (California Coastline).” My hope is that—to riff on Mirikitani’s language—our prayers persist at sea. May they, too, echo in valleys.

Notes

- I do not use the term “documentary poetry” because to me, it denotes poetry that either documents historical events and processes or extensively adapts language from archival documents. Although the basis in history and the archive is the same, with “testimonial poetry,” I intend to describe poetry that focuses on individual experiences and testimonies and takes form largely in persona poems.

- Paisley Rekdal, “千 / Thousand,” in West: A Translation (Port Townsend: Copper Canyon Press, 2023), 66.

- Christine Kitano, “Sky Country,” in Sky Country (Rochester: BOA Editions, 2017), 13.

- Denise DiFulco, “The Celestials,” Williams Magazine, Summer 2013, https://today.williams.edu/magazine/the-celestials/.

- The so-called visitors here were, more accurately, trespassers. They were two divisions of police officers, likely armed, who did not have a search warrant. One division was led by the acting mayor of Denver.

- “CELESTIAL CORRALED: The Police Make a Raid on the Opium Joints And Arrest a Number of Chinamen,” Rocky Mountain News (Denver, CO), Oct. 12, 1880.

- Ana Maria Spagna, “Massacre: Version 1,” in Pushed: Miners, A Merchant, and (Maybe) a Massacre (Salt Lake City: Torrey House Press, 2023), 15.

- Rekdal, “實可 / Indeed,” 9.

- Rekdal, “来 / Journey,” 59.

- Rekdal, “思鄉 / Miss Home,” 71.

- I encourage readers, especially those who do not have easy access to Rekdal’s book, to hear the poems being read out loud by the poet and to interact with the Chinese elegy, to which the poems in West: A Translation respond, on https://westtrain.org/.

- Claire Hong, “Altar,” in UPEND (Blacksburg: Noemi Press, 2020), 26.

- Hong, “How Yellow Men Steal Our Yellow Stuff,” 91.

- Hong, “Neutral Ground 7568,” 7.

- Hong, “Stare at Forest Green to Get Cochineal on the Page,” 80.

- For example, in 1863, the State of Minnesota paid $25 for a Sioux tribe member’s scalp. See more in “VALUE OF AN INDIAN SCALP: Minnesota Paid Its Pioneers a Bounty for Every Redskin Killed,” Los Angeles Herald (Los Angeles, CA), Oct. 24, 1897.

- Hong, “— oOo —,” 47.

- Su Yu-Xin, “A Color Study Leading Towards Materialism,” Su Yu-Xin, accessed May 28, 2025. https://yuxinsu.com/A-Color-Study.

- Hong, “Diamond Scraps of Southeast Alaska, Northern California, Northwest New Mexico,” 86.

- Claire Kageyama-Ramakrishnan, “Collage/Bricolage: Fragments of Truth,” in Bear, Diamonds and Crane (New York: Four Way Books, 2011), 47.

- Kageyama-Ramakrishnan, “Collage/Bricolage: Fragments of Truth,” 58.

- Kitano, “I Will Explain Hope,” 27.

- Kitano, “Fireflies,” 28.

- “90 hou yi shu jia su yu-xin: 22 jian xin zuo, hua xia di qiu de qi li shun jian,” YITART, March 30, 2025, https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/crkAyg2MwBKbm9GKPo9iow.

- Goh, “Letter Home,” 16.

- Teow Lim Goh, “The Last Spike,” in Bitter Creek (Salt Lake City: Torrey House Press, 2025), 6.

- Goh, “Landlocked,” 11.

- Goh, “Letter Home,” 21.

- Goh, “Strikebreakers,” 19.

- Goh, “Faraway Places,” 25.

- Goh, “China Mary,” 39.

- Goh, “Chinatown Burning,” 91.

- Janice Mirikitani, “Paradise,” in Out of the Dust: New and Selected Poems (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2014), 69.

Translated by desi

Weiji Wang grew up in Guiyang, China and lives in Salt Lake City, Utah, where she is a PhD in Creative Writing candidate at University of Utah. She serves as The Nation’s assistant poetry editor.