Liang Shuo: To “Peach Mountain,” and the Circulation of Zha

| January 28, 2026

Liang Shuo wears a mask printed with his own likeness around his neck. Photographed in his study.

Photography by Zhu Mo

Liang Shuo’s studio, nestled in a village about two hours north of central Beijing, was my destination. A pre-departure message from him out of the blue— “Can you bring me a bottle of Coke?”—had me hitting the road with a large bottle in tow. The highway’s monotony lulled me into a post-lunch haze, causing me to miss the transition from city to countryside. My body seemed to have been inexplicably transported to a village that, despite being within Beijing’s administrative limits, felt like any other in northern China. True to his message, there was no Coke, nor a single restaurant to be found.

Upon entering the village, the highest house with a blue roof came into view—Liang’s shared home and studio with his partner, also an artist. Though this was my third visit, it was the first time I noticed that the mountain visible from their living room window was indeed Silver Mountain (Yinshan), part of the Yinshan Talin Scenic Area. This sudden realization grounded my disoriented body. Liang had asked us to arrive in the afternoon the previous day, so we could witness the sunset during our hike up the mountain.

While we were still recovering from the long drive, Liang began by showing us his small painting corner and a set of furniture installations he had crafted from old shipping crates and repurposed late-Qing cabinets he had scavenged. He spoke with care about the glass panels on the cabinet doors, whose painted surfaces had faded into a pale blue-green. In a shrine-like recess of the installation sat a wooden figure, still lacking a face, roughly carved with only a basic outline—but somehow, its character emerged vividly from the fuzzy, fibrous grain of the wood. On the tea table in the living room, he had laid out his “treasures” gathered from various places: pine branches, wood burls, and stones of all kinds. He was full of stories about each one but had no idea what kind of tea was steeping in the pot. As he brewed it for us, he sat across the table drinking his Coke.

What Liang called his “Trashury”—short for Treasury of zha, a term he coined to describe the aesthetic of scraps, residue, remains, and the seemingly insignificant—was a room still under construction in the basement of his house. It contained stacks of blockboard he had accumulated over the years, alongside various painted antique furnishings found in Shanghai and Shenyang. A carefully built architectural model rested on his woodworking table at the center of the room. “Next time you come, the ‘Trashury’ will be finished!” he said, rubbing his hands together in anticipation. We followed him on a full tour of the house, upstairs and down, and by the time we realized it was getting dark, we had nearly forgotten we had come to climb a mountain.

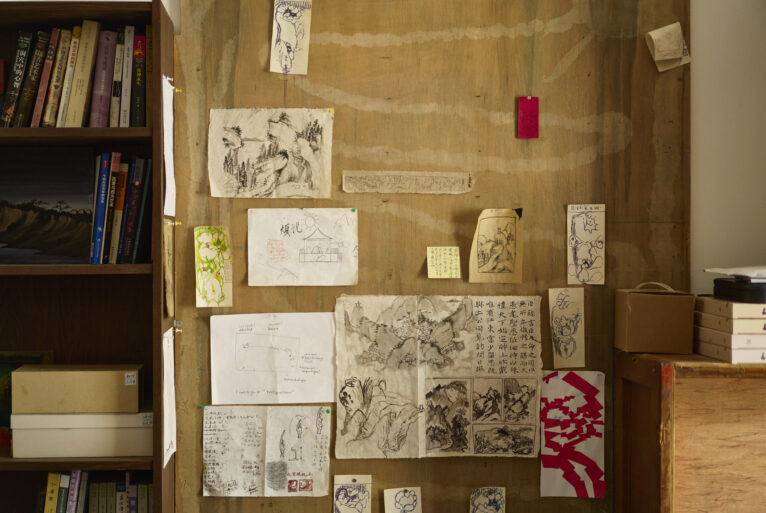

Photographed in the study.

This is where Liang Shuo paints most days.

Instead of leading us up Silver Mountain, Liang guided us down a narrow path towards a neighboring village, stopping occasionally to chat with passing villagers. The trail was easy enough. Bathed in the light of the setting sun, the shades of gray-blue and bright green all around made me feel as though we were walking inside one of his paintings. The scenery was surprisingly dense—compressed, almost. One moment we were facing a wide grassy slope behind a fence, and the next we rounded a corner to gaze at distant peaks. Then came a chestnut grove, with a few elegantly shaped dead trees at its thickest point, and a stream winding between the stones below. Just as we began to relax into the natural calm, we stumbled upon a patch of sand and an abandoned tent.

Entering a valley, we first heard an unseen rumble, then looked up to see a slow-moving freight train inching along a distant mountainside. The creek flowed into a dark tunnel, and while we cautiously waded through the water behind Liang, he had already reached the far end, Coke in hand, humming a tune. Soon, the light at the exit drew us out into another village. Beaming, Liang said, “Didn’t that feel like the Peach Blossom Spring? Come on—I’ll take you to ‘Peach Mountain’!”

That boulder in the woods is what he calls “Peach Mountain.”

Zha and Its Antonyms

Liang Shuo: Look—this pine twig is from the foot of Jade Dragon Snow Mountain. I picked it up during a recent walk in Yunnan.

LEAP: It has a kind of patina. Did you polish it?

Liang: I sanded it with fine sandpaper and then rubbed it against my body to grease it. It’s from the most resinous part of the pine tree. Smell it—what’s changed is only its surface; now it’s smoother, like amber. (He shines a flashlight on the twig as he speaks.) I found it in a farmer’s woodpile. These two were the most translucent, so I brought them back.

Liang Shuo’s collected old furniture.

A signboard Liang Shuo made for his “Trashury.”

LEAP: You’ve collected so many wood boards and old furniture—they remind me of my grandmother’s home. These things must be pretty hard to find, right?

Liang: These are display cabinets I’m preparing for my not-yet-finished “Trashury.” I guess I’ve inherited a habit from my elders—keeping even the smallest scraps of wood. For TV cabinets from the ’80s and ’90s, I usually look for ones with paintings on them. I buy the cabinets for the paintings. Some of them I have restored: for usable boards, I sand them down with fine paper, clean them thoroughly, scrub off all the years of dirt. Broken ones I remove and replace with clean boards. Back when I did a show in Shanghai (“Lai Xixi,” New Century Art Foundation Ceramic House, 2017), I collected a batch there. Later, I went to Shenyang and picked up a lot of pieces in the northeastern style. Northern cabinets are usually not very ornate, but the paintings on them might show traces of Japanese influence.

LEAP: Why do you call them “Trashury”? Are they remnants? Sediments of a civilization?

Liang: I think of them as the scraps of society—those fragmented things that the mainstream has eliminated or ignored.

LEAP: What would you say is the opposite of zha, or scraps?

Liang: Its antonyms might be perfection, maturity, the mainstream? Or maybe wholeness. For example, the academic training we received is the opposite of zha, because it’s so systematized. My search for zha is really a way to treat my own “disease.” I come from an academic background—I know there are decayed things inside me. This is my toy, a way to heal myself.

Zha Circulates among the Folk

LEAP: When it comes to painting, is it ever really possible to let go of our established aesthetic standards—especially those shaped by an elite gaze? Do you see that as a problem? Or how do you deal with it?

Liang: I see myself as a mediator in an ecosystem. What interests me is the complex and fluid relationship between zha and elite aesthetics—there are many overlapping layers between them. It gets really interesting when I can observe how those layers interact. I don’t think it matters much how we define what’s truly “high” or “low,” because once the “high” develops to a certain point, it inevitably starts to recognize something vigorous and alive in the “low,” and then begins to learn from it. Think of Bada Shanren or Picasso—at a certain stage, they began to see the most basic, most primal forms again, and thought: wow, this is incredible—better than what I can do. So they studied them, absorbed them, transformed them—and eventually integrated those elements back into elite aesthetics. It’s a mechanism of renewal, a way to let in new blood. So I see zha not as a style, but as a mechanism—a survival mechanism. If you want to bring your ideas into being, you have to imitate, to collage together the templates you can find, to learn and borrow. And it’s in that process that space for creativity emerges. For example, some of the paintings on the old furniture I collected in the Northeast looked really strange. But as I traced their origins, I realized they were imitating the style of Japanese doro-e—mud paintings. That style itself came about when Japan had closed its borders and only traded with the Netherlands; doro-e was their way of imitating Dutch painting and became an early form of ukiyo-e. When Japan colonized Northeast China, that visual language entered local folk art. Once you know this history, it becomes fascinating. The boundary between “high” and “low” is fluid—they’re constantly in motion. Art history only records the most famous figures, but out in the broader realm of folk culture, it’s never so fixed.

LEAP: So how would you define a folk artist? Would you want to collaborate with them?

Liang: I already consider myself part of the folk. I’m experimenting with a folk operating mechanism on myself. A few friends and I have made mud statues for small village temples—free of charge. We’ve done it several times. It’s like this: I grew up eating millet; later, I stopped for a while—but now I crave it again. So now, I eat both millet and rice—both the old and the new.

LEAP: That sounds like a healthy balance. How did people come to you to make the statues?

Liang: They didn’t—we just went and did it. We told the temple keepers we didn’t want money, and that we’d fund and do the repairs ourselves. As long as they agreed, that was enough.

LEAP: I suppose that’s one way of embodying a folk practice. How did you decide which temples to work on?

Liang: The choice wasn’t about religion. I think of a temple as a space for spiritual comfort. It doesn’t need to belong to a particular belief system—it’s simply a place where empathy is possible. Think about it: someone lives deep in the mountains, something terrible happens at home—their child falls ill with a strange disease. The local doctor can’t help, they can’t afford a hospital in the city—what can they do? All that’s left is to pray, to hope for divine protection. That’s just human nature: when you’re completely powerless, you seek comfort. So I believe the creation of natural gods is one of the most instinctive human behaviors. It’s not superstition in the feudal sense. That label—“feudal superstition”—is just a way of belittling it from an overly rational, scientific, and subjective perspective. But that view is arrogant. Who hasn’t felt helpless? Who can solve everything? Most problems, in fact, are beyond our ability to solve.

A dam — an artificial landscape painted on a cabinet door. From Liang Shuo’s “Trashury.”

After passing through the tunnel, Liang Shuo finds a stream flooding the street at the entrance to the neighboring village. He crouches down, blocking the flow with his forearm like a makeshift dam.

The Anti-Image Shanshui

LEAP: Your relationship with shanshui (meaning “mountain and water,” referring to landscape) painting doesn’t seem to be nostalgic. Nor are you interested in positioning yourself into any particular historical lineage.

Liang: I used to see historical figures like Wang Wei through a kind of halo. But the residency in Wangchuan shifted that. On the one hand, my understanding of Wangchuan had been shaped by Wang Wei’s “classics”—what I saw was filtered through that. On the other hand, the place itself has its own bare, immediate reality.

LEAP: Could you elaborate on that experience?

Liang: It was in 2018 and 2019, when Nan Shan Society in Xi’an invited me to do a residency in Wangchuan, at the foot of the Qin Mountains. Wang Wei is said to have lived in seclusion there. That residency was pivotal for me—it was a process of disenchantment. I had seen Wang Wei as a kind of great master. But when I arrived, I realized his world was just as specific and tangible as ours today. For instance, his retreat wasn’t far from the capital, Chang’an—it was only half a day’s ride on horseback. He wasn’t withdrawing from the world, just taking a break from political life. It was a holiday for the soul. This is typical of literati: wanting both the court and the wilderness. His so-called reclusion was just a comfort zone—a temporary escape. But if the emperor summoned him, he’d be back by sundown. The “Twenty Scenes of Wangchuan” have been polished over by generations of literati, but many of them were simply fragments of his daily life. Some scenes were of places where he farmed—he had to grow food to live. Others were spontaneous encounters: a flock of waterbirds rising, sunlight glinting on a stream—he felt something, and wrote a poem. But these personal, ephemeral impressions were later canonized into the “Twenty Scenes,” and even used as templates for classical gardens. Isn’t that turning something alive into an empty shell? Take the Classical Gardens of Suzhou: exquisite to the extreme, but they represent the tail end of civilization. The roots are forgotten. And the roots are right in front of us—in the ordinary mountain stones and chestnut trees, which are wondrous in their own right. What I felt in Wangchuan was that Wang Wei was just like us. What he saw then, I can see now. Cultural productivity is just projecting a mental state onto the material world.

LEAP: I really liked the concept of the scenic area you introduced in your 2019 solo show at Beijing Commune. The concept felt like a kind of modernized shanshui.

Liang: The scenic area is an important term. If the urban-rural fringe is the border between the city and the countryside, then the scenic area is the threshold between human civilization and nature. It reflects how ordinary people today understand tradition—reproducing shanshui in their own way. Sometimes, we look at it and think, “They really did that?” But that’s zha, isn’t it?

LEAP: Yes—and that’s a kind of zha backed by capital.

Liang: Exactly. Once something gets funding, it can be realized. Artists often complain about not having enough money to make work. But look at these scenic areas—once capital enters, everything gets built. That in itself is vigorous.

LEAP: Your work often incorporates these man-made spectacles. Would you say you have a fascination with artificial landscapes?

Liang: That solo exhibition was mostly painting. No matter how meticulously I painted every detail, it still ended up as merely an image. While I’ve always been against images, that stance comes through more in my installations. My paintings are never derived from pre-existing images. I don’t generate one image from another, nor from an established visual lineage. I’m repelled by constructed image systems—they bore me. It’s the same with shanshui painting. Over time, it became more and more image-based, recycling the same visual vocabulary, becoming increasingly self-referential. Eventually, it couldn’t withstand the impact of Western art. It was, for the most part, killed off—no longer vital. But in its earliest form, shanshui wasn’t so image-oriented. It was an attempt to express one’s experience in nature using two-dimensional forms. It wasn’t copying other images—it was translating a multi-dimensional world. That raw, experimental phase interests me more. When I say “anti-image,” I mean I want to mine from lived reality, not from already-established visual traditions. The moment when an image is generated carries not only temporality but also spatiality. But through endless replication and variation, it loses that spatial quality. What I’m drawn to is that fleeting moment when an image is forming and still holds spatial relevance. It’s subtle, but that’s what I’m chasing.

Photographed at the foot of “Peach Mountain.”

On his way back, Liang Shuo spots an old sewing machine by the roadside and decides to haul it home for his “Trashury.”

LEAP: Do you hike often? What kind of trail are we on today?

Liang: Only when I’m in a bad mood—maybe two or three times a year. Today’s trail is a pretty easy one, the kind you take for a breath of fresh air. Actually, you’ll find a trail on every hill around here. I think this is already the best place in the world. After returning from Yunnan, I realized how small our local mountains are. I’ve been to many majestic peaks, but Jade Dragon Snow Mountain in Yunnan is different. On its north side, there’s a prehistoric site—the Jinsha River rock paintings in caves. I didn’t know it was right next to Tiger Leaping Gorge. When a massive landscape meets prehistoric relics, it throws human existence into sharp relief. It stops being just “scenic” nature meant to be admired.

LEAP: This trail makes me feel like I’m inside one of your paintings—the cool grayish-blues, the vibrant greens. It made me realize: the shanshui in your paintings seems to be northern shanshui.

Liang: Yes, that’s intentional. I consciously paint “Northern shanshui.” Since the Southern Song, Chinese landscape painting has been dominated by southern imagery. There’s been very little about the north, largely because literatis and artists migrated south after the Song. For over 800 years—from Song to Yuan, Ming, Qing, and now—the visual language of shanshui has remained southern. Hardly any new grammar emerged in the north. That’s a problem. It suggests that shanshui painting has long been trapped in a loop—involuted. How is it that in 800 years, the north hasn’t produced any new visual forms? So I gave myself a task: to create northern shanshui. Maybe it’s also because I don’t live in the south—I feel a kind of distance from it. Southern shanshui always feels a bit too cultivated, too refined for me. Overtrimmed, even overpleasing.

(A stretch of sandy ground appears before us.)

LEAP: This too feels like your painting: a blue construction barrier popping up in the midst of green mountains and clear water. I remember being struck by the ending of your essay “Scooping the Home Mountain” (2020, published on wildlands’ WeChat subscription channel). You wrote about revisiting the mountain in your hometown, watching how the scars left by mining had, in just a few years, been absorbed back into “nature” by tender shoots and fresh grass. And in “Ill Rock” (2020—2023, published on Ginkgo Space’s WeChat subscription channel), you described a rock you carried back from a quarry. So what’s the difference between ill and zha? And how do you see these modernized landscapes?

Liang: There’s not much difference, really. “Ill rock” may sound negative, but “ill” is more rhetorical here. It doesn’t mean “bad”—it refers to the part that gets rejected or looked down on. People tend to categorize things: bad should be bad, inferior stays inferior, and we’re not allowed to say otherwise. But I think it’s not about good or bad. Like viruses in our bodies—they may be parasitic, but they’re still part of our biological system. Or museum objects: they appear to be carriers of knowledge and history, but in fact, they’re carefully constructed narratives, shaped layer by layer by institutions and experts. They may come from the past, but what we see is not the original “site.” This spring, artist friend Cheng Xinhao took me to Mount Cock Foot in Yunnan, along an old trail Xu Xiake once walked. There were bits of broken rock everywhere. I realized these shards resembled prehistoric stone tools. We always think things from “tens of thousands of years ago” are remote, but we’re still making similarly mundane objects every day. What we call “the past” or “the classics” is often just right in front of us.

LEAP: So this disenchantment of the “classics” is also a way of undoing cultural authority?

Liang: Exactly. We’re always chasing what’s already been validated—those things that are constructed and explained by professionals—while neglecting the everyday. There’s so much value in the ordinary, but we’re often not prepared to see it. Of course, to peel back the layers of cultural packaging, you also need to prepare yourself in terms of understanding.

LEAP: It seems you’re always looking back?

Liang: Yes. But looking forward and looking back aren’t so different—they both rely on imagination.

Liang Shuo stands atop “Peach Mountain,” with village power lines strung overhead.

To Live in the Mountains Is to Return Home

LEAP: Why did you move to this village?

Liang: I first wandered into this place by chance, and honestly, it never crossed my mind that I could actually live here. I thought, how could I possibly “deserve” to live in a place like this? Not in this lifetime! But during the pandemic, my partner and I were stuck in a tiny apartment in the city. It was unbearable, and we just wanted a place with a courtyard. A housing agent told us there was a house in the mountains. At first, I didn’t even want to go see it—mountains? That’s retirement living, I thought. You go into the mountains when you’re done with everything. I told myself I wasn’t that old yet. Still, we ended up going. Along the way I kept thinking, this place is way too far out. But as soon as we entered the village, I realized—I’ve been here before! And the house we came to see was the exact one we had passed during that earlier walk.

LEAP: Do you see the mountain as your studio?

Liang: Not at all. The mountains feel like home to me. The landscape here is basically the same as where I grew up.

LEAP: I remember your hometown had some connection to the quarrying industry?

Liang: Yes, my uncle is a stonemason. So is my current landlord. The two places are very similar—the landforms, the rocks, the vegetation, even the people. When I was a kid, the rocks I saw were all quarried by hand. I remember watching entire boulders being split into small square blocks, the kind used in cities. That’s how villagers made their living. So from a young age, I understood the relationship between humans and nature as one of survival—you live off the land, you make use of what’s around you. It felt completely natural, not something you judged by whether it was eco-friendly or not. I used to think, sure, the Earth is our mother, and we’re just exploiting her without giving anything back. But then I thought, aren’t we just another type of parasite on the planet? We live off it. If we don’t mine its resources, how else are we supposed to survive? That said, we do need to have reverence. Nowadays, people take “human dominion over everything” as a given, as something beyond questioning. That doesn’t sit right with me.

(We pass through a dark railway tunnel.)

LEAP: Where are we now?

Liang: We’ve already crossed into another village. That stretch we just walked through—it felt a bit like The Peach Blossom Spring, didn’t it? People from our village use that path when they’re harvesting fruit, and herders from this village bring their sheep through here too. See that boulder up on the hillside? That’s our destination for today. It’s kind of magical—there’s nothing else around it quite like it. It’s the largest rock in the area, and it seems to have just landed there in this hollow. So strange. It looks like a godly peach split into three perfect segments.

LEAP: Was it formed naturally?

Liang: I’ve looked closely. There are no chisel marks or drill holes—nothing that suggests it was worked by human hands. No idea how it split into three so evenly. Maybe the Monkey King will jump out of it one day, haha.

Interview and text by Dai Xiyun

With contributions from friend Nie Xiaoyi and editor You Yiyi

Translated by Wu Zhuxin and You Yiyi (with the help of AI tools)

Liang Shuo, who also goes by “Nao Liang” (literally “cool-brained”) and “Dafen” (after Dafen Oil Painting Village), was born in a mountain village in Ji County (now Jizhou District, Tianjin, China). He graduated from the Sculpture Department of the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA, China) and was an artist-in-residence at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. A member of the group “Diao Dui” (literally “lagging behind”), he now teaches at CAFA.Liang roams mountains and ancient sites, finding beauty in the wilderness and zha—a term he coined to capture the aesthetic of residue, remains, and the seemingly insignificant. He attends to the bond between land and life, between separation and reunion, past and present. His thinking and practice move beyond disciplines, following the rhythm of wandering. He currently lives and works in a mountain village north of Beijing.

Dai Xiyun is an independent curator and designer based in Beijing. Her research explores the mechanisms of desire in spatial experience, urban media and storytelling, and the translatability between image, text, and space. She places particular emphasis on co-production and locality in her curatorial practice.