Common Sense and Sacred Sites: Rethinking Ecological Art and Its Landscapes

| January 30, 2026

Text by Yuan Fuca

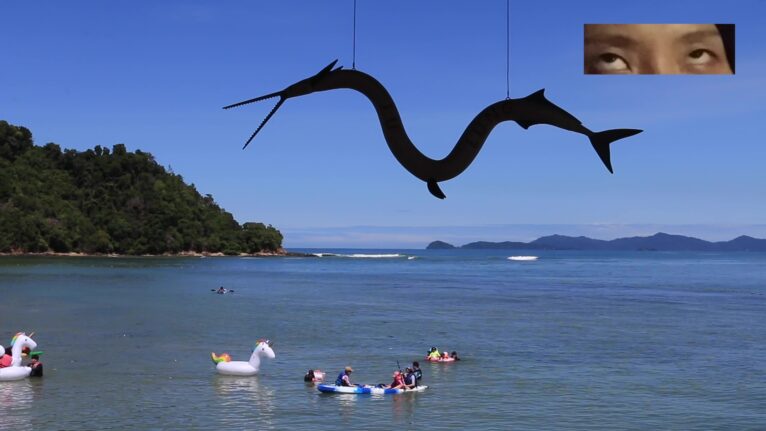

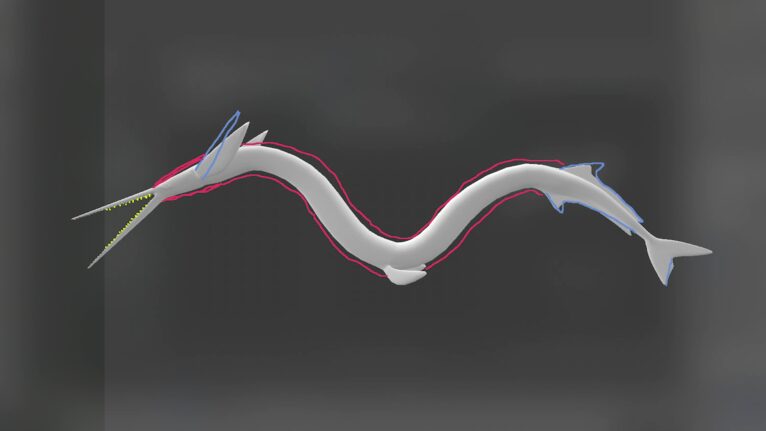

Yi Xin Tong, The Birth of Julung-julung: The Aquatic Dragon, 2019–2021

HD video with sound (24 min 52 sec), percussion instrument made of metal and wood (110 × 34 × 15 cm)

Courtesy the artist

My journey into ecological art as a curator and researcher truly began in 2019, during a residency project I curated in Sabah, Malaysia. Shortly after the residency began, the Indonesian government announced its decision to move the national capital from Jakarta to central Kalimantan. This thrust the once-peripheral tropical rainforest island into the spotlight of national governance and ecological development, prompting me to reconsider the spatial politics of “center” and “periphery.” The five-month residency—which happened just before the COVID-19 outbreak—marked my entry into the intersection between marginal zones and ecological crisis.

On this tropical island, long treated as a colonial resource and ecological testing ground, I first encountered the Julung-julung (a dragon-like fish), and came across artist Yixin Tong’s bio-instrument and video work inspired by it—a sculpture resembling a deity, with upturned eyes in a trance-like gaze. This piece not only connected the ocean, mythology, and the body, but also drew my attention to Borneo’s highest peak—a sacred mountain in the eyes of the Indigenous peoples.

This particular artwork sparked my interest in “mountains” as carriers of knowledge. In subsequent fieldwork, I came to realize: a mountain is not merely a geographic structure—it is a source of language and a container of time. In the gaze of the Julung-julung, I perceived a latent narrative intertwining mountain and sea, water, wind, and geology. This non-linear, anti-sovereign vision of landscape offers a path of learning in ecological art—not about “knowledge of mountains,” but about the ability to coexist with mountains.

Yi Xin Tong, The Birth of Julung-julung: The Aquatic Dragon, 2019–2021

HD video with sound (24 min 52 sec), percussion instrument made of metal and wood (110 × 34 × 15 cm)

Courtesy the artist

From above, the island resembled a Möbius strip—a structure with only one side and no boundary between inside and outside. With no clear entry or exit, it symbolized my methodological turn: from observer to immersive co-dweller. In other words, I began to see curating and writing not as extractive acts, but as ways of being—practices of negotiating rhythms of coexistence.

In In the Realm of the Diamond Queen (1993), anthropologist Anna L. Tsing studied the Meratus Dayaks of South Kalimantan and proposed that “cohabitation” is not about achieving uniformity, but the juxtaposition and negotiation of heterogeneity—a way to re-understand tradition, power, and community amid cultural and institutional entanglements.

Since 2020, I have slowly traversed the Hengduan Mountains in southwest China: from Diqing to Nujiang, from Nangqian to the Dulong River. Rather than conducting “research,” I found myself absorbed by the terrain—through the scent of plants, the angle of rock strata, the low-frequency silence of certain nights. This drew me into a form of knowledge beyond maps or legends. There, the sacred was not about religious worship, but a sensed entanglement—a mutual presence between humans, mountains, and water that defied assertion.

Nangchen, 2022

Photo by the author

Dulong River, 2022

The Hengduan Mountains, born from the collision of the Indian and Eurasian plates, is a site of rupture and extreme ecological diversity—and geopolitical fragility. The geological concept of “deep time” becomes here a philosophical tool, reminding us that human history is just a fleeting wrinkle on a geological scale. Artistic intervention in such landscapes cannot merely present sacredness—it must learn to listen in silence to geological languages and to adjust bodily rhythms in the face of tectonic shifts.

In this process, the “body” is no longer a mere mediator between subject and nature—it becomes the site of knowledge production itself. Fieldwork turns into a tuning of rhythms and frequencies—a practice of resonance with the non-human, rather than interpretation of cultural difference. Highland winds, hearth temperatures, linguistic disruptions, plant veins—these non-verbal elements together form a kind of “sensory geography” or “co-dwelling geomancy,” in which humans are neither central nor sole perceivers.

The geological folds of the Hengduan Mountains also gave rise to cultural diversity. Indigenous cosmologies offer alternative linguistic worlds: the Lisu people believe the soul originates in mountain winds; Nu villages worship “Anuyi” (Mountain Spirits) before major events; the Derung people view humans, mountains, water, and trees as part of an energy-exchange cycle. These “mythogeographies” are not premodern residues but knowledge systems symbiotic with landforms—embodied, rhythmic, spatially embedded. In them, rupture becomes passage, sediment becomes the trail of ancestral return. They show us that topography is not merely physical—it is a resonant structure of history and perception.

Antonio Gramsci noted that “common sense” is a kind of “assumed certainty”—a way to simplify complex historical relations into manageable spatial orders. In contemporary ecological governance, this simplification tends to isolate crises from structural issues like colonialism, resource extraction, and Indigenous sovereignty loss. Common sense, at its core, masks structural relations and converts them into operational logics—a phenomenon especially evident in climate governance.

However, in many Indigenous societies, “common sense” is a profound cosmology—sustained by ritual, mythology, and ecological practice. It is a structural relation of sacred and everyday life. When institutions try to translate this knowledge into “cultural assets” or “resource metrics,” they often strip it of sacredness, reducing it to tools of display and control.

This has been sharply critiqued by Glen Coulthard and Eve Tuck, who argue that institutional “recognition” of Indigenous peoples rarely entails real sovereignty. Instead, it neutralizes the autonomous power of Indigenous knowledge. To rethink the possibility of “sacred landscapes,” we must acknowledge Indigenous common sense as a confrontational landscape technology—a logic of resistant survival.

In this context, the role of art is not to represent, translate, or memorialize—but to ask deeply: which common senses are being activated? Which sacred beliefs extracted? Which faiths commodified? Curatorial work must become a de-imaging, embodied methodology, allowing knowledge to “rest” and then reawaken relationally at the right moment.

Zhao Yao, Spirit Above All, 2016

Zhao Yao, Spirit Above All, 2016

On November 23, 2016, between 9 a.m. and 6 p.m., Spirit Above All, roughly 10,000 m² in size, was unfolded at the top of Senggaiga Mountain with the help of 150 people, including lamas from the Moye Temple and local people from Kaze Village.

Courtesy the artist and Ota Fine Arts

As I walked through the Hengduan terrain, I realized that the body is not a passive container of knowledge, but a mechanism of its generation. In the spruce forests of Gaoligong, in Nujiang’s nocturnal whispers and breezes, I learned to slow down, tune my breath, and enter an asymmetric, purposeless rhythm of the landscape. This rhythm came not only from nature’s pulses, but from ethical tensions in the field: when to speak, when to pause, when to only listen.

Rhythms of the body—motion sickness, insomnia, language barriers—became sources of knowledge. Co-dwelling requires constant tuning—with both the non-human and one’s unstable inner tempo. Sleepless nights in the highlands became entry points into landscape resonance.

On one trip, we passed through Nangqian, Qinghai—a mountainous valley between destinations where artist Zhao Yao had placed his abstract thangka. It was also where artist Tong Wenmin performed in a river valley (called “Anung Remai Zmai” in the local Anung language) near the Nu River’s source. In a stone house, she enacted a ritualistic performance, guided by intuition. In that moment, I felt the immense energy within the mountains.

Tong Wenmin, A Passage into the Mountains and Rocks… as Eternal and Serene as Death, 2022

Tong Wenmin, A Passage into the Mountains and Rocks… as Eternal and Serene as Death, 2022

Performance video. Nangchen, Qinghai

Courtesy the artist

Of all the artists I’ve worked with, Tong Wenmin’s practice most tellingly provides a concrete and visceral entry point into embodied knowledge. Using plants as medium, she inscribes sunlight, skin, and time into “delayed performances.” She crawls through forests, dances by hearths, floats on water—not for spectacle, but to reconfigure the body into a sensory instrument for experiencing landscape. In this way, the body becomes an echo of the mountain and a seismograph of the landscape. Meanwhile, Timur Si-Qin’s conceptual framework of “New Peace” expands on this idea by juxtaposing Buddhist imagery, consumer language, and natural objects. This creates a ritual space where technology, nature, and spirit resonate, reminding us that embodied knowledge can be global, technoscientific, and posthuman, not just local.

Timur Si-Qin, Untitled (before the wild pig) 1, 2024

Aluminum, gesso, uv print, 170 × 130 × 3.5 cm

Courtesy the artist and Magician Space

Timur Si-Qin, Luorong Rock, 2024

Resin, bronze, LED screen, 200 × 150 × 50 cm

Courtesy the artist and Magician Space

In my recent curatorial and writing practice, “healing” is no longer about soothing or repairing, but a fluid process of recalibration. This evolution stems from personal experiences in mountain-border regions, where the exhaustion of curatorial work, the demanding nature of knowledge extraction, and a deep yearning for authentic community coalesced into a slow, profound self-inquiry. This exploration is no longer about validating existing meanings, but rather about re-establishing connections with nuanced rhythms and unspoken relations. In this practice, the body transcends its role as a mere instrument; it becomes a vessel for attunement and heightened perception.

Tsing’s work on the Meratus Dayaks, who inhabit similar ecological and political landscapes to my Sabah residency site, highlights their use of marginality as a method, shifting and negotiating between systems. Her description of “inward journeys”—spiritual crossings by female shamans—prompted me to reflect on my own experience as a female researcher. I considered how mountain walking transforms the body into a perceptual extension, a sensor traversing both terrain and memory. Healing does not reject rupture—it sees rupture as a point of reconnection.

Returning to the northeast in early summer 2025, I participated in the residency project of “Changbai Spring.” Changbai Mountain, a place I knew more from family photos than direct experience, felt both familiar and alien. Its designation as a “border” is a relatively recent historical construct, despite a century of restricted access. While it functions as a political frontier, ecologically it is recognized as a rich biodiversity hotspot.

Before arriving, I had attempted to connect with the sacred mountain through various means, even purchasing Qing Dynasty ritual incense (such as azalea incense) on Taobao, hoping its fragrance would evoke some faint ancestral memory. However, these efforts proved unnecessary once I was actually on the mountain.

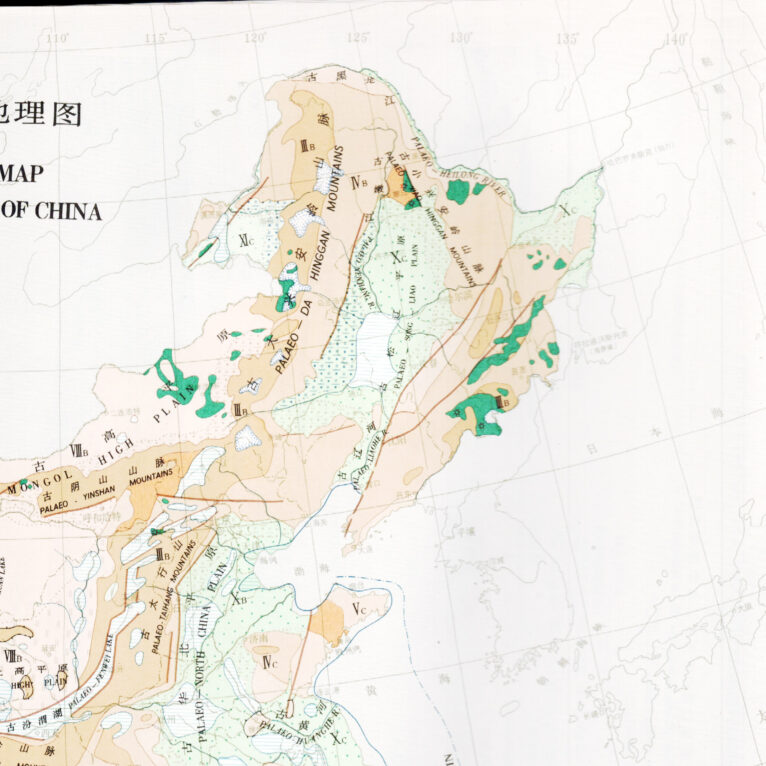

The northeast area in the Palaeogeographic Map of the Early Pleistocene of China, scanned from Atlas of the Palaeogeography of China (1985)

Courtesy Liang Chen

During a presentation at the residency, architect Liang Chen showed a hydrological map of Changbai Mountain. It was then I came to the realization that a so-called sacred mountain is not merely a symbolic terrain of ethnic origin—it is the water container of the Northeast Plain. The Songhua, Yalu, and Tumen Rivers all originate there. Water is more than a fluid form—it is a fundamental logic of life.

Perhaps it was in that moment that I fully grasped what Indigenous scholars mean when they say the sacred is not an abstract spirituality but a spatiotemporal network of relationality and materiality. It does not descend from the authority of distant deities; it is constituted through water’s veins, the contours of land, and sustained practices of care. In this system, the mountain does not stand silently at a distance—it enters our bodies as water, day after day, forming the most imperceptible yet elemental stratum of perception.

Reflecting on the link between Changbai’s hydrological function and its perceived sacredness, I recalled the Subak rice-irrigation system discussed in Hildred Geertz and Clifford Geertz’s Kinship in Bali (1975). Subak is not merely hydraulic infrastructure; it is a complex socio-ecological formation embedding cosmology, land governance, and community organization. Its aim is not efficiency but the maintenance of sacred order. Water’s movement from volcanic highlands to terraced fields is read as cosmic balance—a continually renewed contract among humans, spirits, and ancestors. Each channel is tied to a temple network, and allocation is coordinated not by markets or states but by extended kinship.

Extending kinship to non-human entities—water, paddies, mountain spirits—offers a generative reversal: water is allocated through relation; the sacred is not an abstract value, but an ethic enacted through the technologies of shared inhabitation of land and water. Compared with the mountain-water cosmologies of peoples in the Hengduan Mountains, or the geomorphic logic by which Changbai nourishes the Northeast Plain, the Balinese case demonstrates an institutionalized, kin-based, decolonial knowledge structure. This hydraulic kinship articulates a non-linear, co-temporal sense of time: water does not travel in a straight line from source to terminus, but cycles in seasonal rhythms—at once agricultural calendar and the material tempo of belief.

Tibetan Fox, Nangchen, 2025

Photo by the author

Nangchen, 2025

Photo by the author

From Mount Kinabalu to the Hengduan Mountains to Changbai, each trekking itinerary underscores a shared fact: water is not simply a material resource—it is a structuring axis around which knowledge, perception, and governance coalesce. It entangles body, landscape, and institution within a directional web, positioning the sacred not as symbolic projection, but as structural emergence. At these points of intersection, we begin to see how artistic practice can enter into this terrain of spatial, relational, and spiritual entanglement—offering a mode of knowing that diverges from both Enlightenment rationality and romanticized ecology.

Crossing mountains, water flows in layers—branching, nourishing the lowlands, sustaining humans and other beings. The sacred is a spatiotemporal mesh, composed of water veins, terrain, and care. It anchors our daily practices of cohabiting, co-drinking, and co-becoming with the land. As an Indigenous proverb reminds us, “We do not own the land; the land owns us.” I would add: we do not worship sacred land—for we have already been raised within its waters.

Yuan Fuca is a writer, curator, and researcher based in Beijing and New York City. She is the Associate Program Director for China at Kadist, a co-founder and artistic director of initial research in New York.